A Greenland Shark Born in 1620 is Still Alive Four Centuries Later

The Timeless Wanderer of the Arctic Depths

Imagine a creature so ancient that it was gliding through the icy waters of the North Atlantic when Galileo first aimed his telescope at the heavens, when Shakespeare was still penning his final plays, and when North America was yet to be mapped in full. A living witness to the rise and fall of empires, the invention of the printing press, the harnessing of electricity, and the birth of the digital age—all without making a sound.

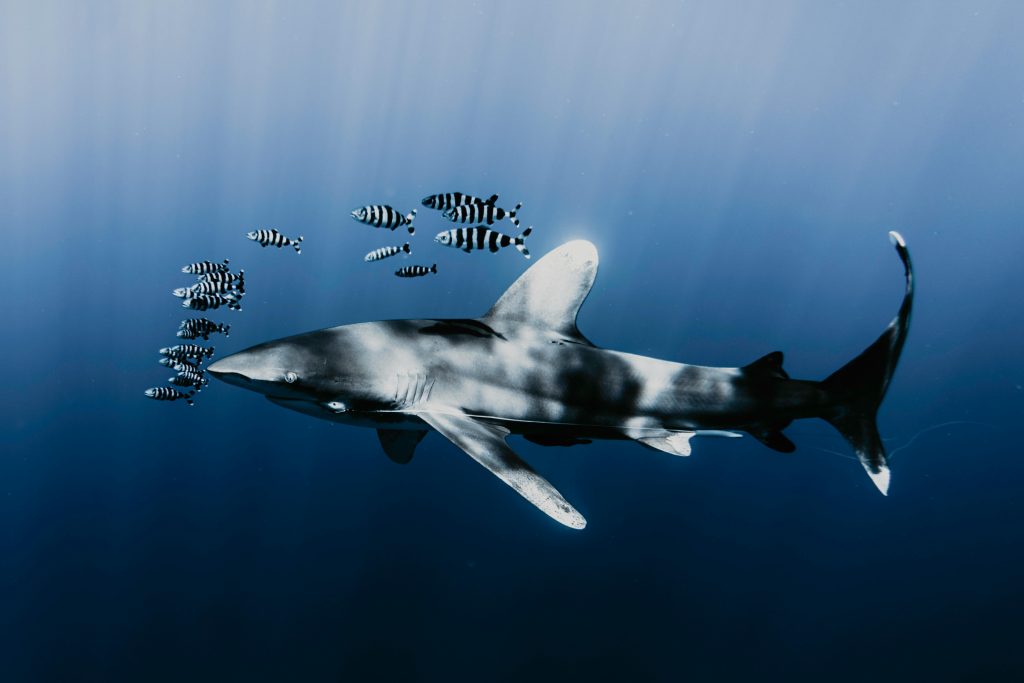

This is no sea monster from sailors’ lore, no mythical leviathan etched into faded nautical maps. It is the Greenland shark—an elusive giant of the deep that holds the record as the longest-living vertebrate ever known. One female, born around 1620, is still alive today, slowly sweeping through the darkness with the unhurried patience that only centuries can teach.

A 400-Year-Old Mystery

How can a shark live for four centuries? What biological secrets are locked within its thick, scarred skin and glacier-chilled blood? Scientists are only beginning to unravel the puzzle—a puzzle that challenges almost every assumption we’ve made about aging, resilience, and the limits of life.

At the heart of this longevity is an extraordinarily slow pace of life. Greenland sharks grow at just 1 centimeter per year, taking centuries to reach their maximum size—up to 7 meters in length and over a ton in weight. Even more astonishing, they do not reach sexual maturity until about 150 years of age, making them the slowest-developing vertebrates on record.

Their frigid home is another piece of the equation. Dwelling in the deep, cold waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, where temperatures hover just below freezing, these sharks live in an environment that naturally slows down their metabolism, heart rate, and overall cellular activity. A Greenland shark’s heartbeat thumps a mere 10 times per minute, and it cruises at about 0.76 mph—earning its nickname, the “sleeper shark.” This slow-motion lifestyle dramatically reduces wear and tear on the body, delaying the onset of aging.

How We Learned Their Age

For decades, scientists puzzled over how to determine the age of Greenland sharks. Most fish can be aged by counting growth rings in calcified tissues like bones or scales, but Greenland sharks lack such structures. The breakthrough came when researchers discovered that the proteins in the lens of their eyes remain chemically “frozen” from birth. Using radiocarbon dating—a technique more often used in archaeology—scientists analyzed these proteins and found a female estimated to be about 400 years old, with an age range of 272 to 512 years.

Dr. Julius Nielsen, who led the groundbreaking 2016 Science study, admitted:

“We had our expectations that we were dealing with an unusual animal, but everyone involved was astonished to learn they were that old.”

This discovery dethroned the bowhead whale, which was thought to live up to 211 years, and redefined the upper limit of vertebrate longevity.

The Arctic’s Secret to Time Travel

The Greenland shark’s apparent ability to “cheat time” may lie as much in its world as in its biology. The pitch-black depths they inhabit—often between 600 and 2,000 meters—are shielded from sunlight and free from many predators. The absence of ultraviolet light reduces DNA damage, and the stable, high-pressure environment limits environmental stress.

Life in the slow lane has its costs. Many Greenland sharks carry parasitic copepods attached to their eyes, impairing or even destroying vision. Yet they survive by relying on other senses—possibly even detecting faint electromagnetic fields—to find prey.

From Target to Victim

Historically, these sharks were heavily hunted for their livers, which yield oil prized for lamp fuel and lubricants before petroleum products became common. Tens of thousands were killed in the early 20th century, leaving deep scars in their population.

Today, they are more often killed accidentally as bycatch in deep-sea fishing nets. An estimated 3,500 Greenland sharks are caught unintentionally each year—an alarming figure for a species that may take a century and a half to reproduce. Most caught today are still juveniles in biological terms.

Dr. Nielsen warns:

“It is rare to find sexually mature females or juveniles in surveys. That makes sense, as the oldest sharks were lost to historical fishing. It could take hundreds of years for the population to recover.”

An Enigma of Reproduction

One of the most frustrating unknowns is how they reproduce. No one has ever documented Greenland sharks mating or giving birth in the wild. Scientists suspect females may bear up to 10 pups after a multi-year pregnancy, but this remains speculative. Without knowing where and when reproduction occurs, conservation becomes guesswork.

What They Might Teach Us About Ourselves

The Greenland shark may also be a living laboratory for aging research. Its resistance to age-related diseases, its efficient heart function, and its apparent ability to maintain cellular stability over centuries have piqued the interest of biomedical scientists. Studying its genome and immune system may one day yield insights relevant to human longevity and disease prevention—though such applications are still far off.

Even the method used to determine its age—Bayesian statistics—adds a poetic twist. The technique is named after Reverend Thomas Bayes, who lived in the 18th century, during the very lifetime of some of the sharks studied.

Why Saving Them Matters

Protecting the Greenland shark is not just about preserving a species—it’s about safeguarding a living archive of Earth’s history. This shark began life in an ocean untouched by modern industry, centuries before railroads, electric lights, or the Internet. Its survival into the next millennium depends entirely on whether humans can curb deep-sea bycatch, limit habitat disruption, and address climate change.

As marine conservationist Amanda Costello puts it:

“This is not about the next five or ten years. It’s about protecting a species that could still be here in the year 2425.”

In an age of vanishing wildlife, the Greenland shark stands as both a warning and a beacon of hope—a reminder that endurance, patience, and adaptation can sustain life across centuries, if only we give it the chance.

News in the same category

10 Types of Toxic Friends to Avoid

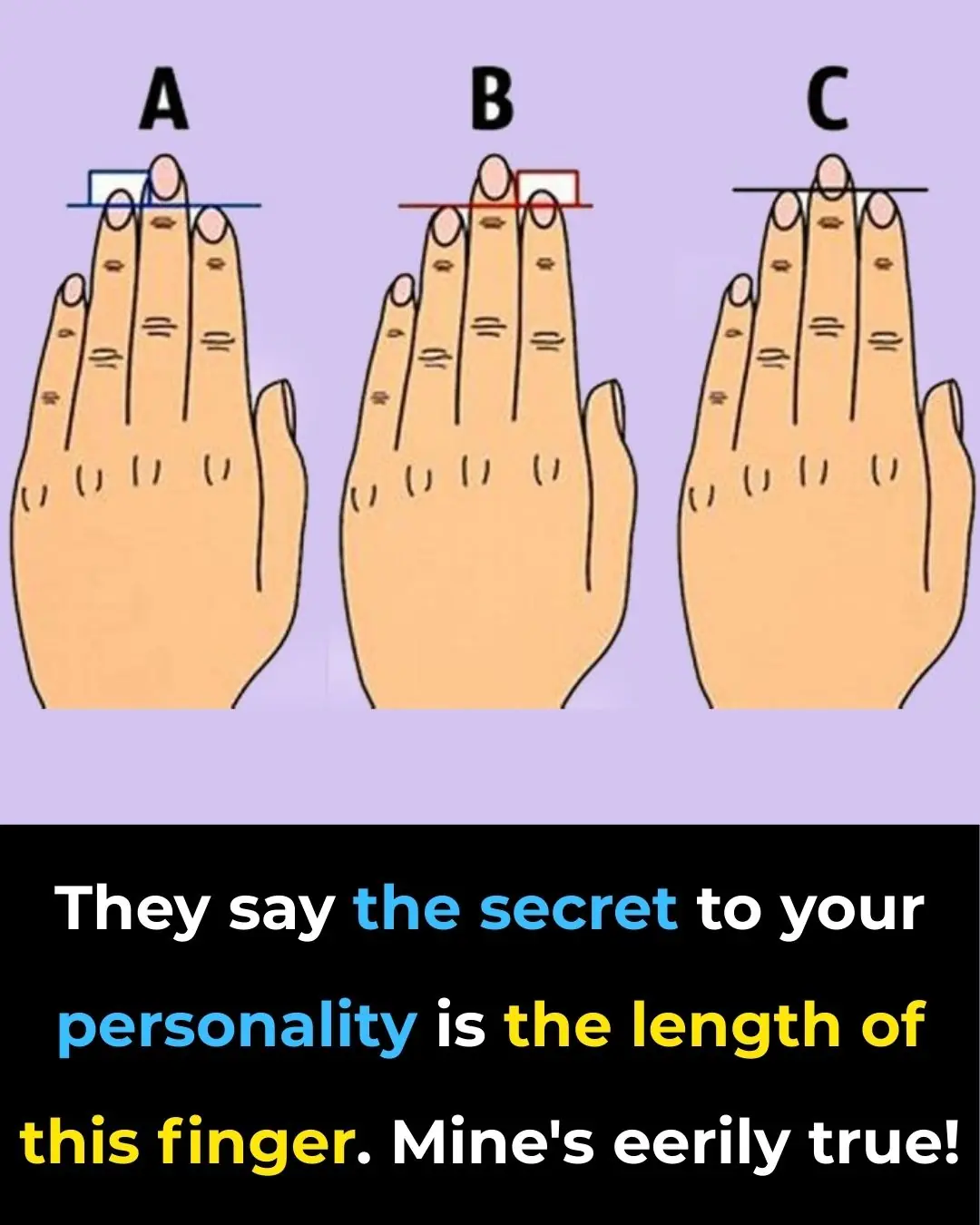

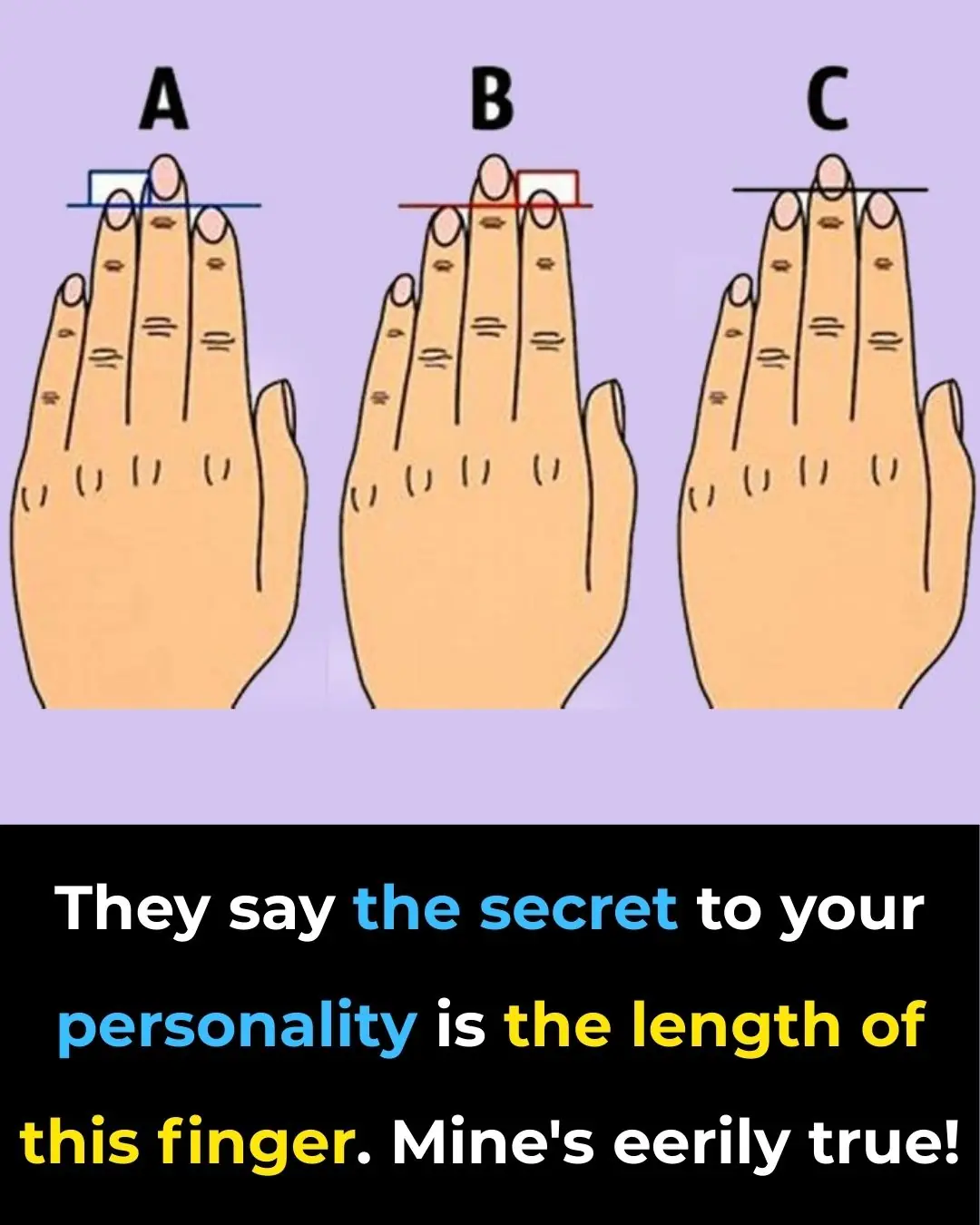

Index Finger Length: Personality and Fortune

Underwater City Near 'Noah's Ark' Discovery Might Change The Bible Story We Thought We Knew

Reason Mark Zuckerberg Just Spent $15,000,000,000 to Hire This 28-Year-Old ‘College Drop Out’ for Meta

Cut a lemon in four and keep it in your bedroom overnight – the reason is brilliant

This lemon trick is a small change that makes a big difference.

Italy just upgraded dogs to cabin class. No more cargo holds for dogs!

11 Heartbreaking Signs Your Dog Is Nearing the End—And How To Give Them The Love They Deserve

15 Things That Might Hint at Her Romantic Past

Depressing find at the bottom of the Mariana Trench is a warning to the world

The Mariana Trench, Earth’s deepest ocean abyss, was once thought to be untouched by human hands. But the discovery of a single plastic bag in its darkest depths has become a chilling symbol of how far our pollution has reached.

Unveiling Personality Secrets: What’s the First Color You See?

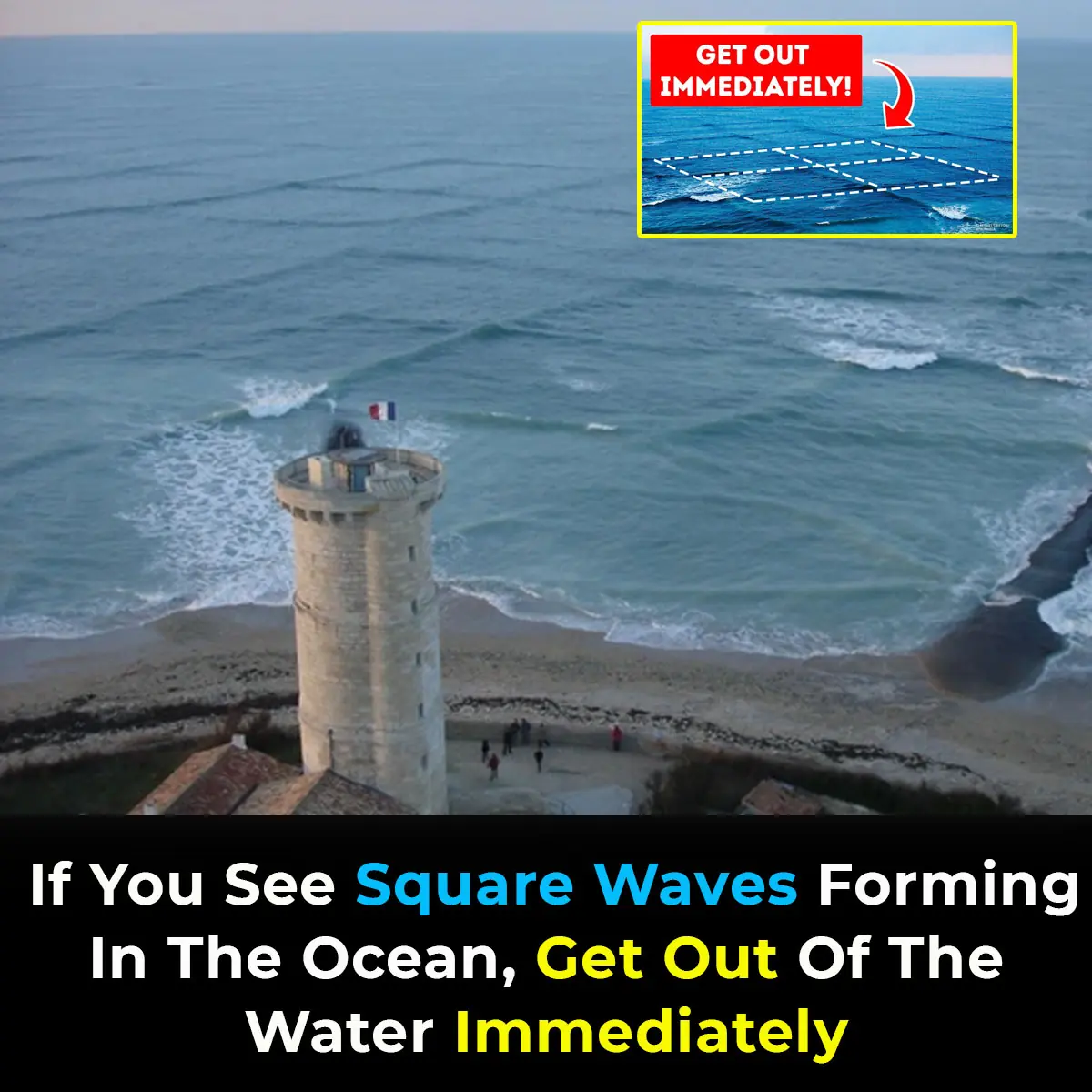

If you see square waves forming in the ocean, get out of the water immediately

The mesmerizing chessboard-like patterns on the ocean’s surface may seem harmless, but they’re hiding a dangerous secret. Scientists warn that these rare formations, known as square waves, can turn the sea into a deadly hazard in seconds.

The flowers you love the most uncover hidden aspects of your personality

Flowers don’t just brighten our surroundings — they can also serve as a fascinating mirror to our inner world. From the joyful daisy to the mysterious violet, your favorite bloom could reveal your emotional depth, values, and the way you connect with

Experts warn: Don’t swap your oven for an air fryer

The Truth About Eating the Black Vein in Shrimp Tails

This is why you should keep the bathroom light on when sleeping in a hotel

Leaving your hotel bathroom light on at night might seem unnecessary, but it could be a small habit that makes a big difference for your comfort and safety. From preventing nighttime accidents to deterring intruders, experts say this simple tip can protec

The Mystical Gaboon Viper, Master Of Disguise And Deadly Accuracy

If You See Square Waves Forming In The Ocean, Get Out Of The Water Immediately

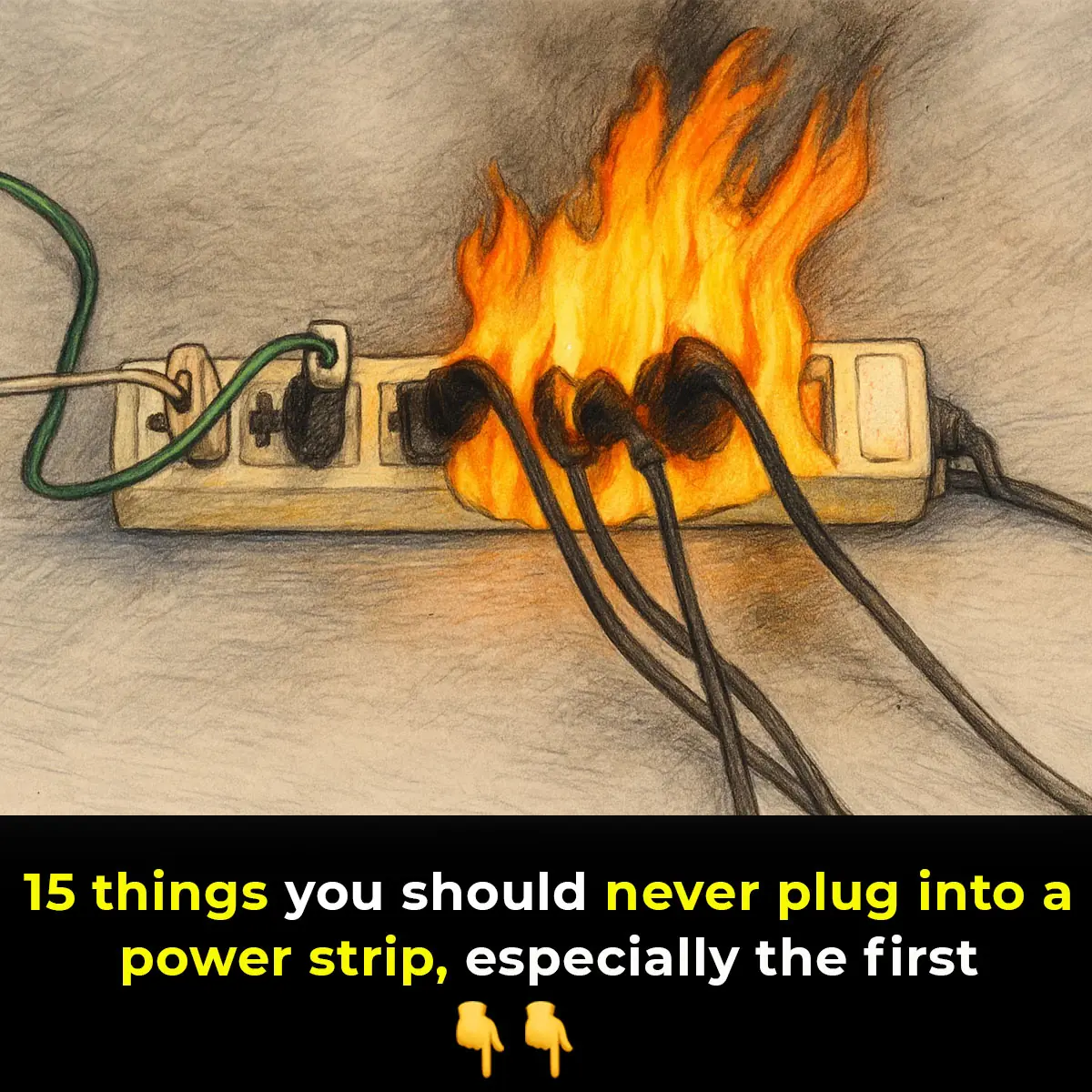

15 Things You Should Never Plug Into A Power Strip

News Post

14 Warning Signs of Low Magnesium Levels and What to Do About It (Science Based)

5 Unconventional Signs of Breast Cancer That You Must Know About

Low FT3 Levels Predict Risk for Nerve Damage in Diabetes

Doctors Urge: Don’t Ignore Unexplained Bruising — These Hidden Reasons Could Be the Cause

12 Urgent Warning Signs You’re Eating Too Much Sugar

5 Common Habits Silently Destroying Your Liver (Most People Do Them!)

Where Do You Stand on the Sitting-Rising Test?

The Ultimate Guide to Marinating Fish

The Pros and Cons of Sleeping with a Fan On

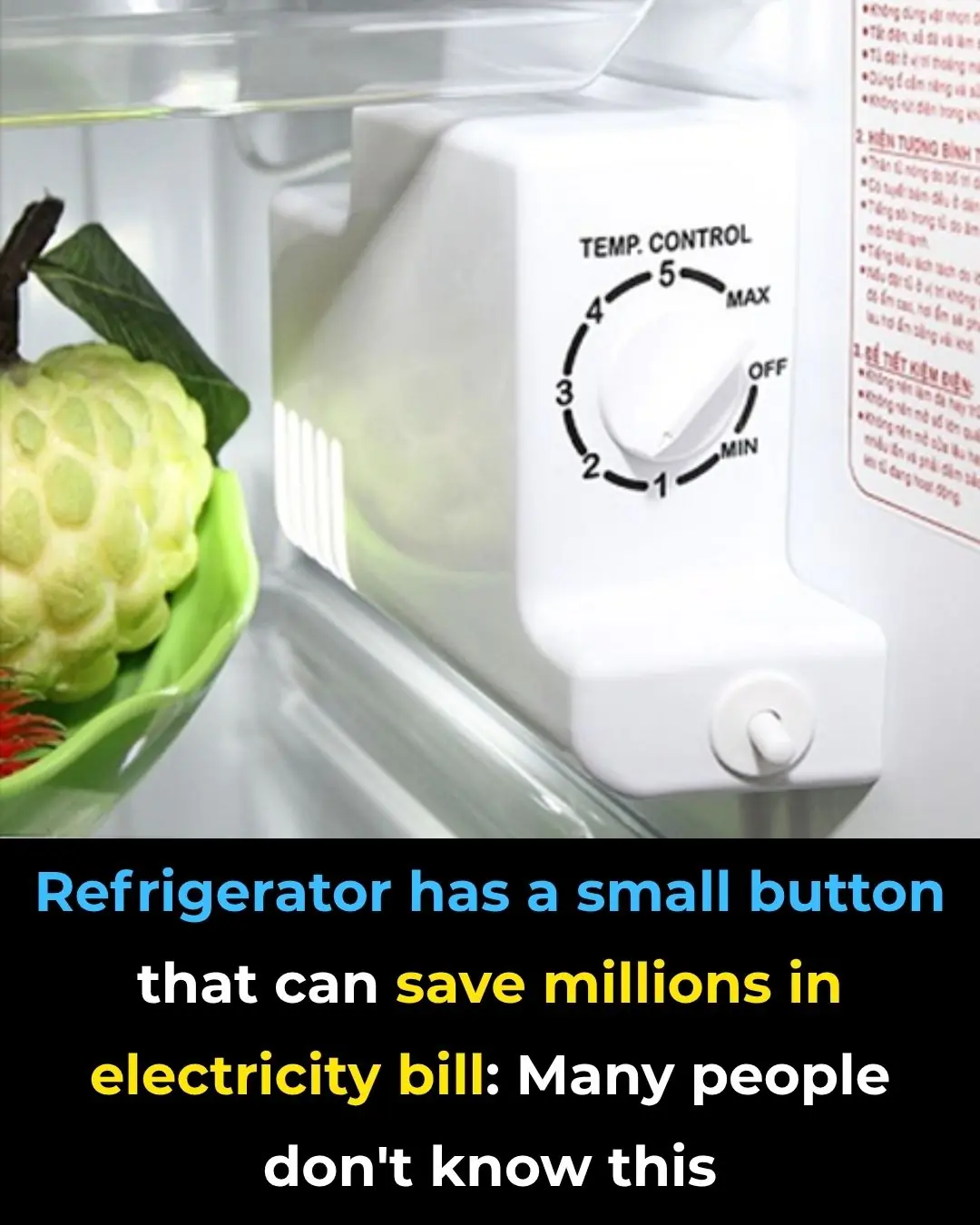

One Button, Big Savings: Cut Energy Costs with Every Wash

10 Symptoms of Kidney Disease

10 Types of Toxic Friends to Avoid

Index Finger Length: Personality and Fortune

5 Potential Health Benefits of Macadamia Nuts

How to Exercise Safely When You Have Atrial Fibrillation

How to Get Rid of Dead Dry Skin on Feet

Foods to Eat if You Need to Poop – The Best Natural Laxatives

How to Make Onion Juice for Hair Growth & Strong Hair

3 Best Ways to Boil Sweet Potatoes for Maximum Flavor