Alaska’s Rivers Turn Orange as Thawing Permafrost Releases Toxic Metals

Rivers in northern Alaska are increasingly turning bright orange as the Arctic warms and the once-permanent permafrost beneath the landscape begins to thaw. This striking transformation has been observed across many waterways in the Brooks Range and adjacent Arctic regions, where long-buried minerals are being released into rivers and streams — coloring them with iron and other metals that were previously locked in frozen ground.

The phenomenon was first noticed from the air by pilots flying over remote parts of northern Alaska, who reported seeing river networks shaded in shades of rust and orange rather than their typical clear blue. Initially, these discolorations looked like signs of industrial contamination, yet there are no mines or factories nearby to explain them. Scientists now link the unusual coloring to naturally occurring minerals leaching into waterways as thawing permafrost exposes soils and rocks to water and oxygen.

Unlike typical pollution caused by human activity, the changes in Arctic river chemistry stem from climate-driven processes. Permafrost, the layer of soil that remains below freezing for years or even millennia, has been acting as a natural seal for iron and other trace metals. As global temperatures rise — especially in the Arctic, which is warming faster than any other region on Earth — this frozen ground begins to thaw, allowing oxygenated water to penetrate and dissolve previously locked-away minerals.

As a result, more than 75 streams and rivers in the Brooks Range have been reported with elevated iron concentrations, leading to a rusty hue visible even from satellite images. In many cases, scientists report that the water not only has a rich orange appearance due to oxidized iron, but also contains increased levels of other heavy metals such as zinc, copper, nickel, and cadmium — some of which can be toxic to aquatic life at high concentrations.

The chemical processes at work parallel what happens in acid mine drainage, where sulfide-rich rocks exposed to oxygen generate sulfuric acid that leaches metals into streams. But here, there is no mining involved. Instead, it is the climate-induced thaw of permafrost that is exposing sulfide minerals and accelerating these geochemical reactions in the Arctic — once a perpetually frozen region.

These shifts in water chemistry affect more than just aesthetics. Many affected rivers now exhibit higher acidity, greater turbidity, and significantly increased concentrations of metals — changes that can stress aquatic ecosystems. Elevated metal levels have been linked with declines in macroinvertebrate diversity and fish populations, including salmon and Arctic grayling, which depend on clear, cold water for spawning and feeding.

Iron and aluminum particles can soil riverbeds, reducing habitat quality for insects that form the base of the food web. Metals like cadmium and copper can be toxic even in trace amounts, interfering with fish gill function and reproductive health. In some streams, pH levels have dropped to values similar to vinegar, a sign of high acidity that further threatens aquatic organisms.

The implications extend beyond wildlife. Indigenous communities and rural villagers depend on these rivers for subsistence fishing, transportation, and, in some cases, drinking water. Although current metal concentrations in edible fish tissue do not consistently exceed recommended limits for human consumption, the long-term ecological consequences and potential for future contamination require careful monitoring.

Researchers emphasize that the orange rivers are a visible indicator of broader Arctic change. As permafrost continues to thaw due to global warming, the chemical landscape of Arctic watersheds is being altered in ways that were previously unseen in such pristine regions. This makes the “rusting rivers” an important early warning sign — not just for Alaska, but for climate-sensitive ecosystems around the world.

In summary, the striking orange-colored rivers of northern Alaska are a natural, climate-driven phenomenon caused by the release of iron and other metals from thawing permafrost. These metals, once trapped by frozen ground, are now entering freshwater systems and posing new challenges to aquatic life, local communities, and the broader Arctic environment — underscoring the rapid pace of environmental change in a warming world.

News in the same category

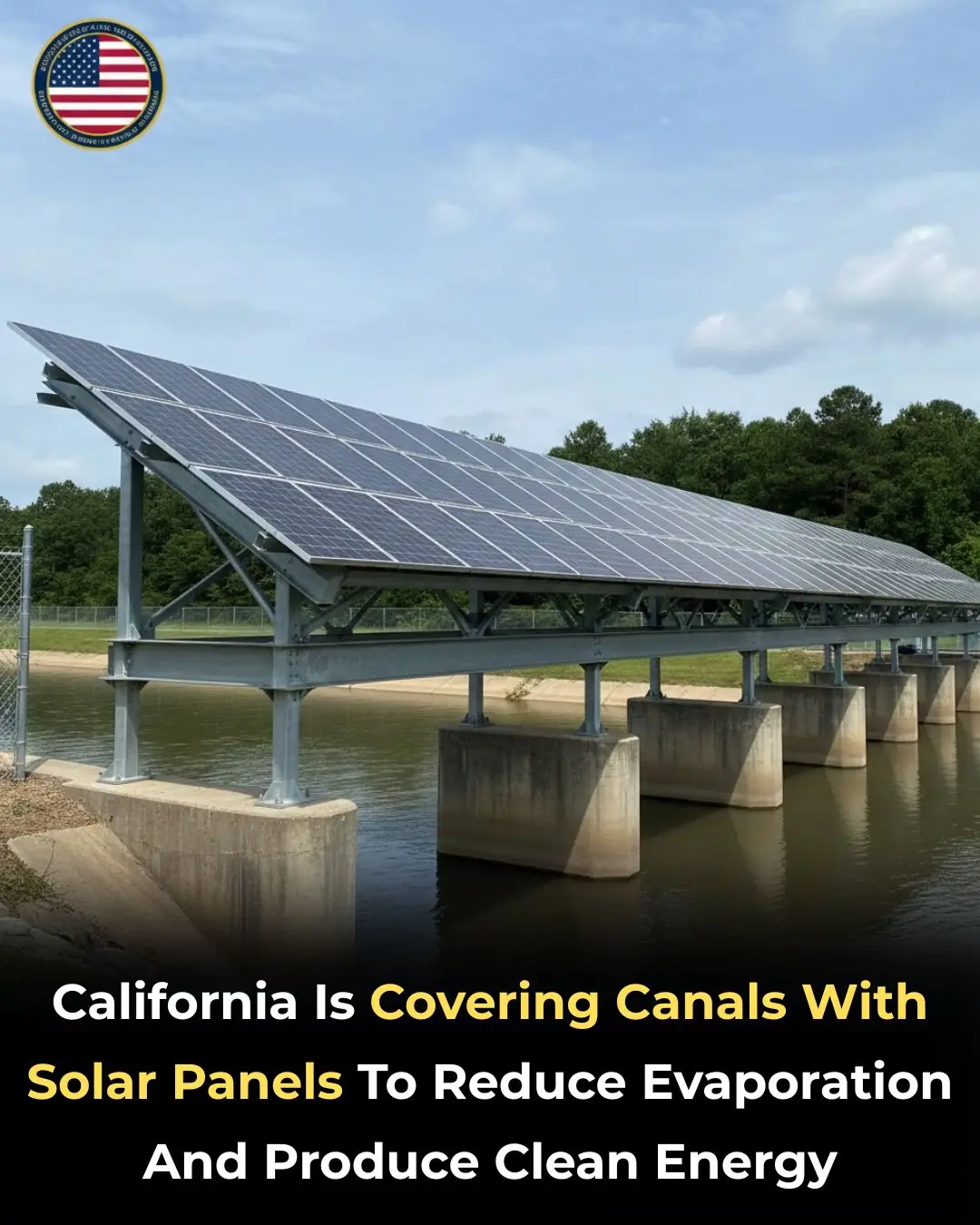

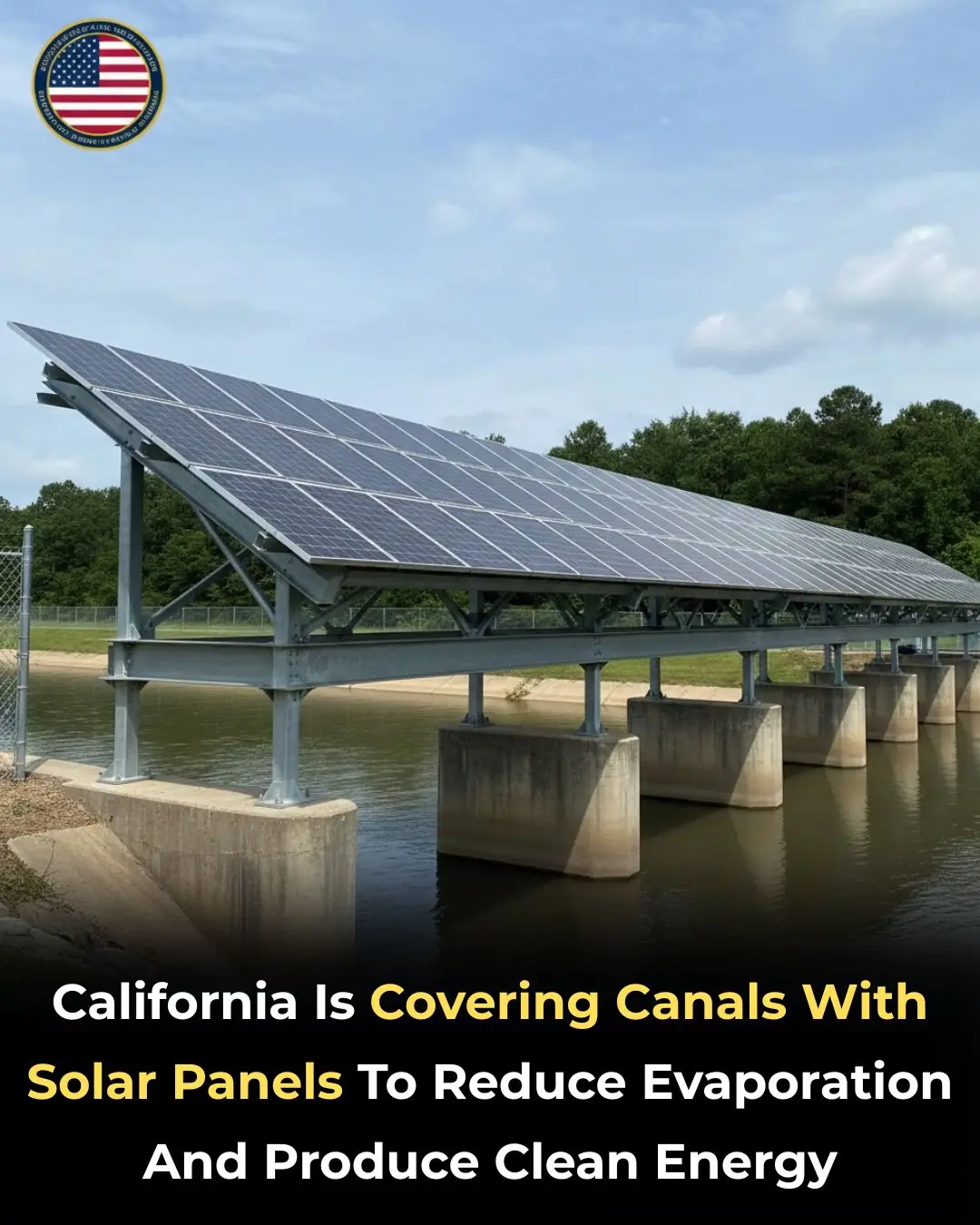

California Turns Irrigation Canals Into Solar Power and Water-Saving Systems

Jesy Nelson's celebrity friends including ex Chris Hughes show support as Little Mix singer reveals twin girls' devastating diagnosis

Chiefs confirm Patrick Mahomes tore ACL in left knee

Elon Musk Just Became The First Person Ever Worth $600 Billion

From Stage Lights to Ring Lights: Young Thug’s Atlanta Proposal Stuns Fans

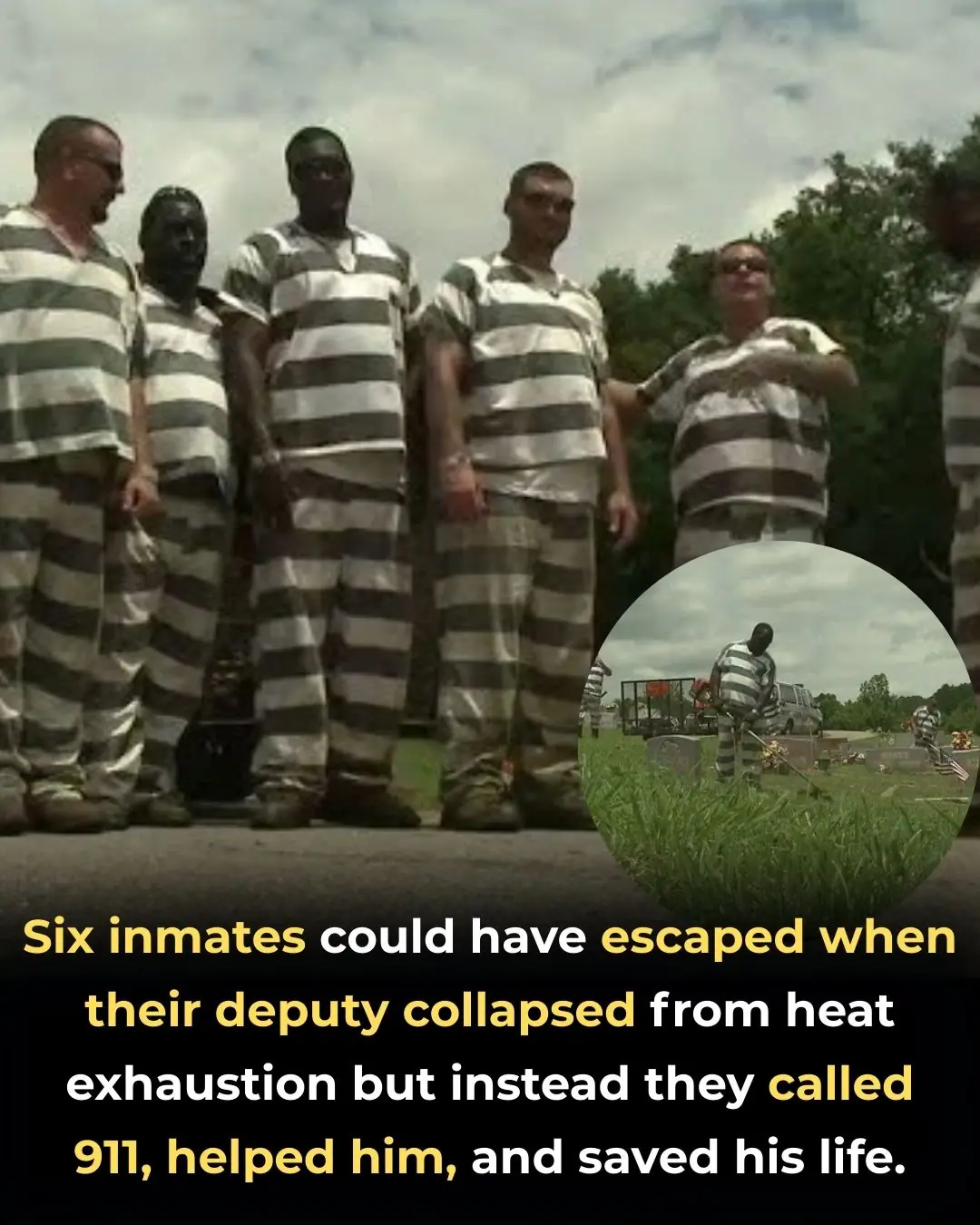

Six Georgia Inmates Risk Nothing and Save Sheriff’s Life

Condolences: Angela Yee Shares Her Brother Passed Unexpectedly At 51 After Suffering From An Aneurysm

Rethinking Land Use: Protecting Forests Through Redevelopment

Woman at center of viral 'kiss cam' moment at Coldplay concert breaks silence

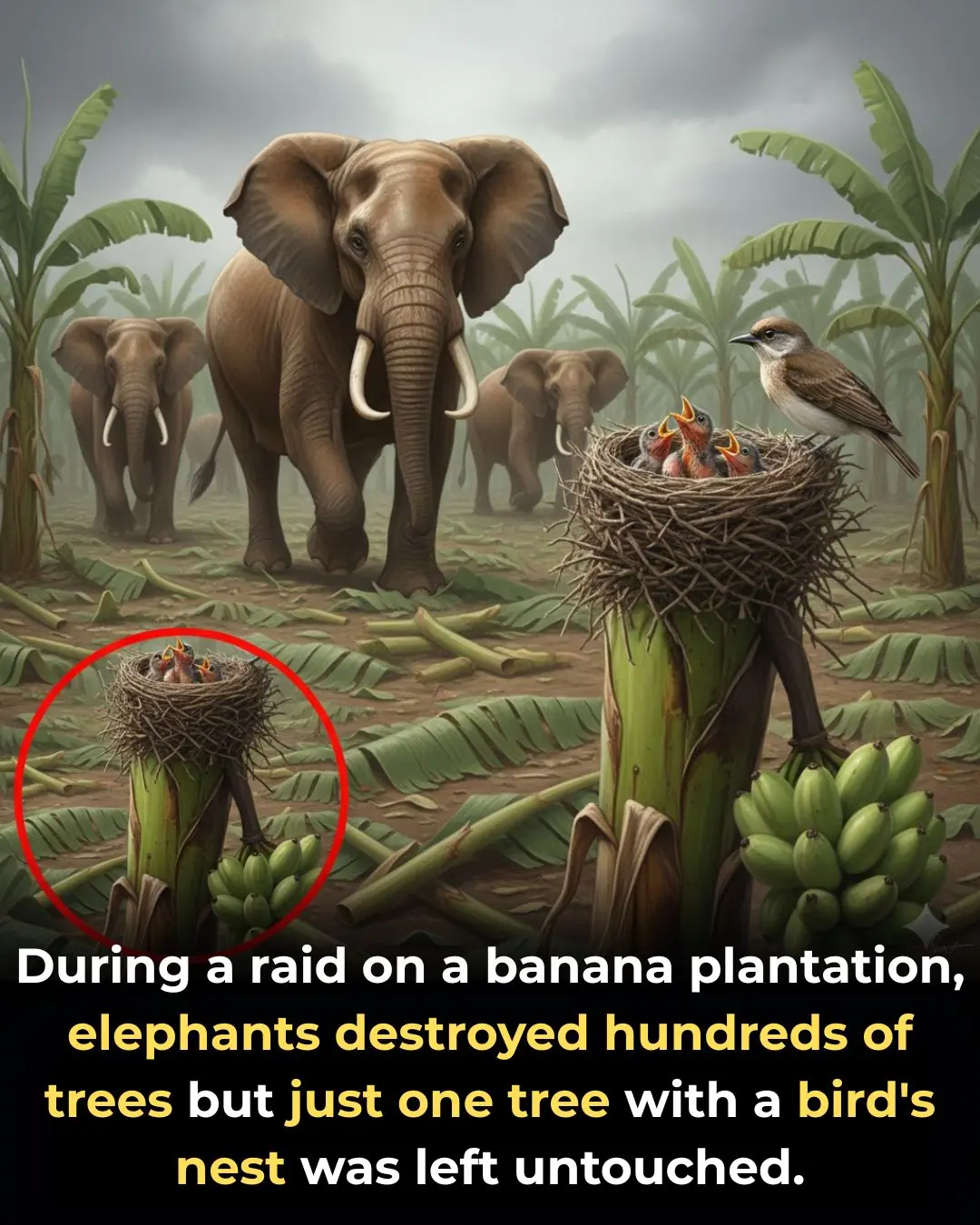

Elephants Spare a Banana Tree with a Bird’s Nest Amid Widespread Destruction

Award-Winning Tech Influencer Lamarr Wilson's Cause of Death at 48 Revealed

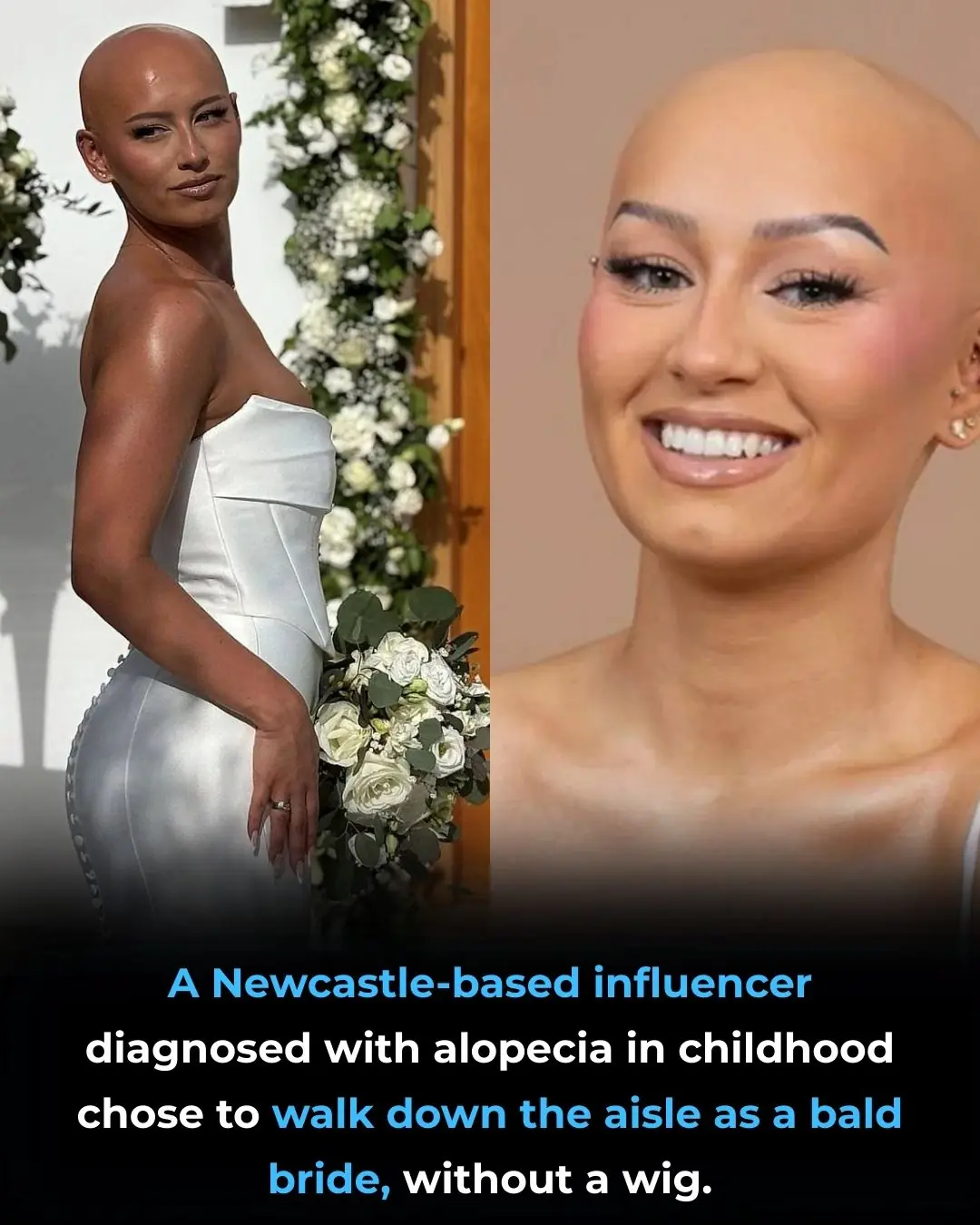

Bride With Alopecia Walks Down the Aisle Wig-Free, Celebrates Authenticity on Her Wedding Day

Bride Embraces Alopecia, Walks Down Aisle Wig-Free to Celebrate Authenticity

Nicki Minaj deportation petitions explained as over 120,000 people sign amid backlash

A Wife’s Six-Year Sacrifice: Nurul Syazwani’s Heartbreaking Journey of Love, Care, and Grace

Historic Victory: Yurok Tribe Reclaims 47,000 Acres of Ancestral Land in California

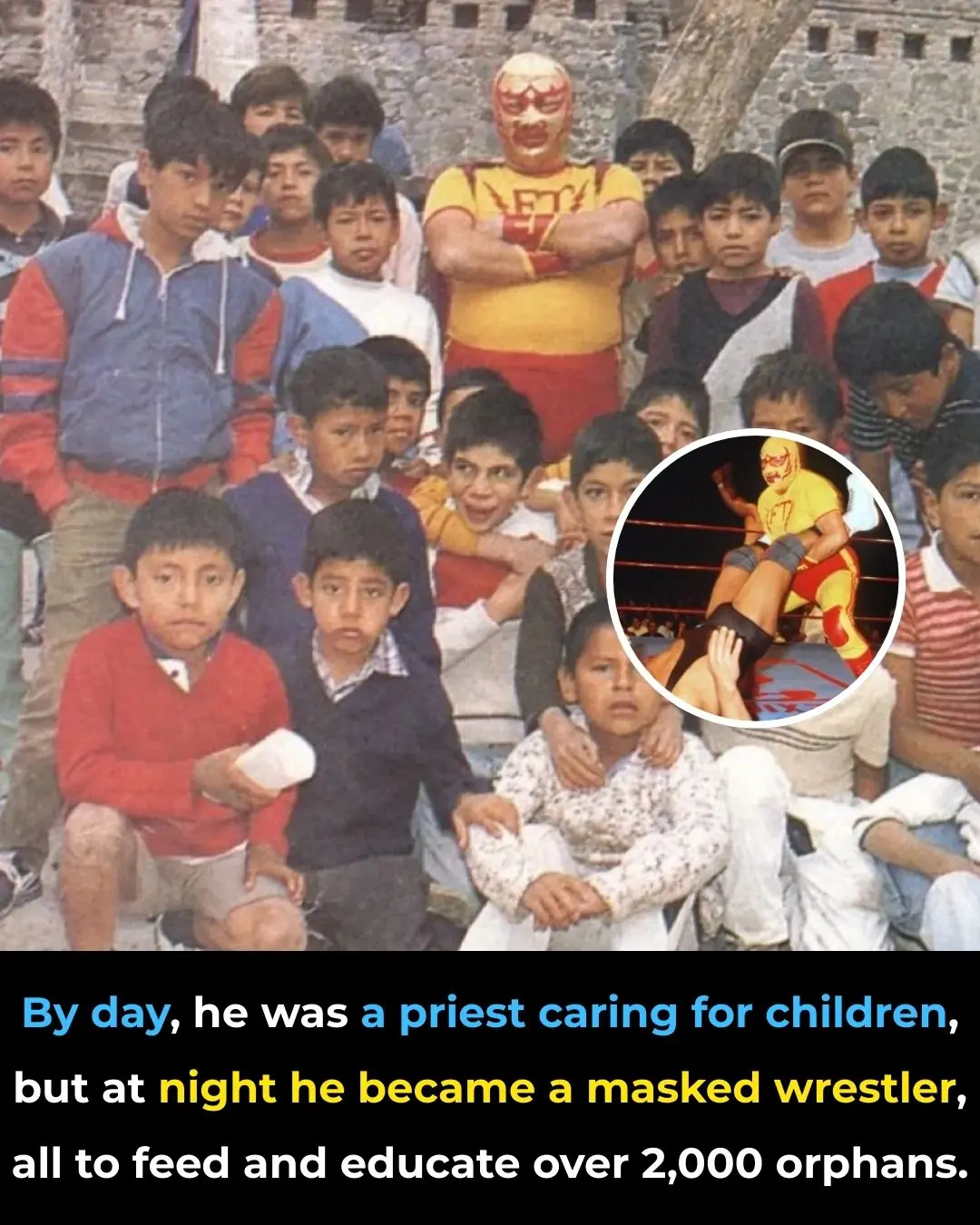

The Priest Who Became a Masked Wrestler: The Real-Life Story Behind Nacho Libre

Flying Back in Time: How Crossing the International Date Line Let Passengers Celebrate New Year Twice

News Post

Medicine Breaks New Ground as Ultrasound Builds Tissue Without Surgery

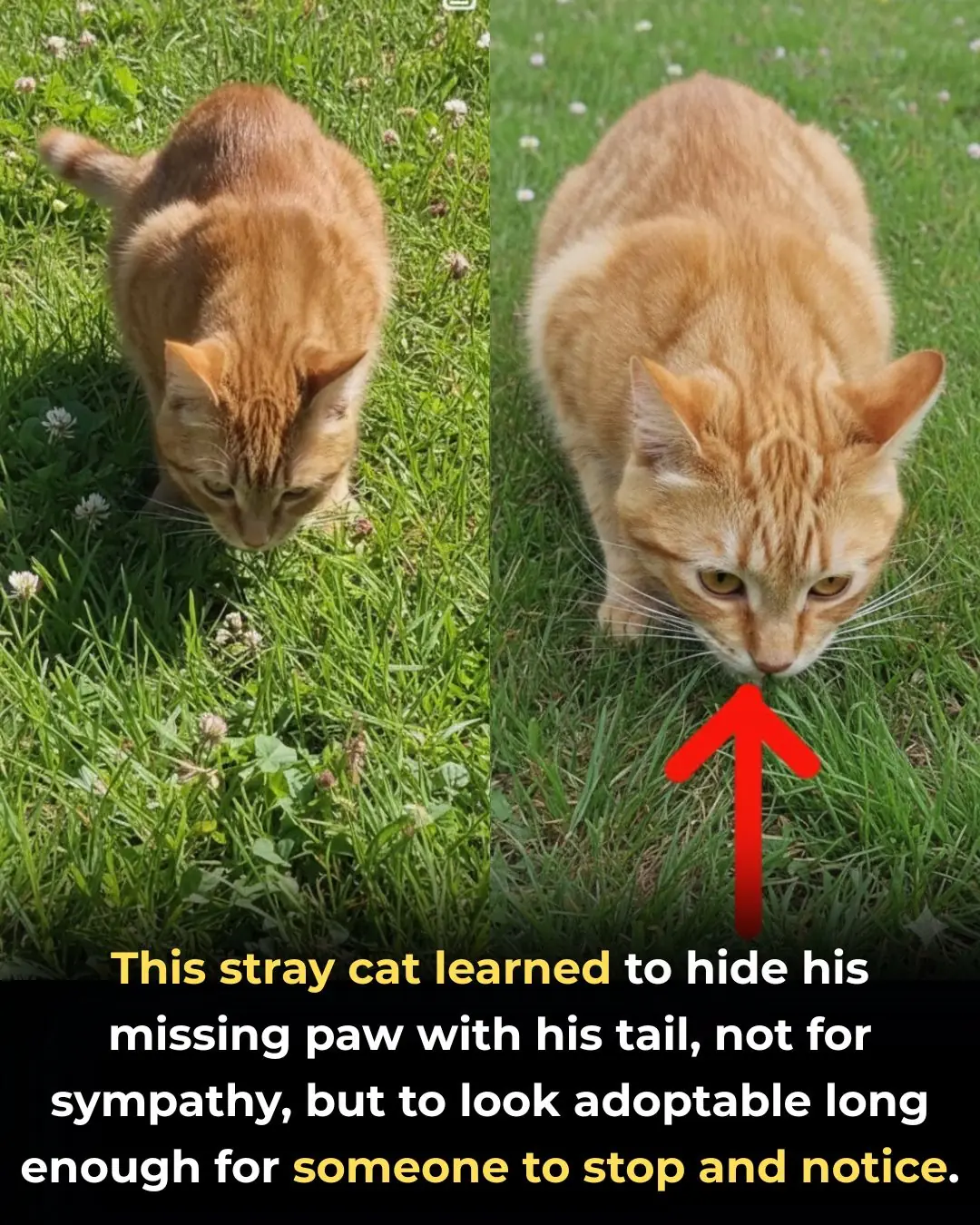

A Heartbreaking Survival Trick: How a Stray Cat Learned to Hide His Pain

Bears Turn Honey Theft Into a Surprising Taste Test in Turkey

Scientists Say Your Butt Shape May Say More About Your Health Than You Think

The Rare Condition That Makes Human Bones Slowly Vanish

Mexico Ends Marine Animal Shows and Sparks a Health Centered Conservation Shift

California Turns Irrigation Canals Into Solar Power and Water-Saving Systems

Jesy Nelson's celebrity friends including ex Chris Hughes show support as Little Mix singer reveals twin girls' devastating diagnosis

People with weak kidneys often do these 4 things every day: If you don't stop soon, it can easily damage your kidneys

Get Soft, Pink Lips Naturally: A Simple DIY Scrub for Smoother Lips

Over 60? Waking Up at 2 A.M. Every Night? This One Warm Drink May Help You Sleep Through Till Morning

7 Everyday Foods That Help Maintain Muscle Strength and Stay Active After Age 50

Oregano for Eyes: The Little Leaf That May Protect Your Vision After 40

I spent a couple of nights at my friend’s previous apartment and saw these unusual bumps

The Healing Power of Small Gestures in Hospitals 💧💕

From Coal to Clean: Maryland’s Largest Solar Farm Goes Live 🌞⚡🌿

Understanding the Link Between Your Blood Type and Health

I swear, I didn’t have the faintest clue about this!

Jeff Bezos: “Earth Has No Plan B” — Why Industry May Need to Move Into Space 🌍🚀