Modified Herpes Virus Shrinks Advanced Melanoma Tumors in Trials, Offering Fresh Hope Against Stubborn Skin Cancer

From Cold Sores to Cancer Cures: How a Common Virus Is Being Transformed Into a Life-Saving Weapon

Viruses are often perceived as nature’s troublemakers—uninvited invaders that bring with them colds, fevers, and flare-ups like cold sores. But in an extraordinary twist of modern science, one such virus is being reengineered not to harm, but to heal. The herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), long known as the culprit behind those painful mouth blisters, is now emerging as a powerful new ally in the war against cancer.

In a remarkable scientific breakthrough, researchers have modified HSV-1 to selectively target and destroy cancer cells. By altering its genetic structure, they’ve transformed a once-maligned virus into a potent form of immunotherapy—one that not only infiltrates malignant tumors but also calls upon the body’s own immune system to join the fight.

This isn’t a futuristic concept or a speculative lab experiment—it’s already happening in clinical trials around the world. In particular, patients with advanced melanoma—a notoriously lethal form of skin cancer that often resists treatment—are experiencing something few dared hope for: tumors that shrink or even disappear entirely.

Turning a Virus from Villain to Hero

The concept of using viruses to fight cancer—known as oncolytic virotherapy—may sound like science fiction, but it's firmly rooted in decades of research. HSV-1 is especially well-suited for this task. Unlike newer viral vectors, herpes has been studied extensively. Scientists understand how it behaves in the human body, how it spreads, and how to control it using antiviral medications. This makes it both a reliable and modifiable platform for cancer therapy.

Central to this transformation is the ability to manipulate HSV-1’s expansive DNA genome. By removing the genes that cause illness and replacing them with genes that boost anti-cancer activity, researchers can create a virus that seeks out and destroys cancerous cells while leaving healthy tissue untouched.

One of the pioneers in this field, Prof. Susanne Bailer at Germany’s Fraunhofer Institute, helped develop a version of HSV-1 with built-in safety mechanisms. These genetic “switches” ensure that the virus can only replicate inside cancer cells. Once inside, it multiplies until the cancer cell bursts—a process known as lysis—releasing tumor fragments that alert the immune system to the presence of disease. This not only destroys the original tumor but helps the body recognize and attack others, even those not directly treated with the virus.

RP1: A Smart Virus Designed to Kill Cancer

At the forefront of this revolution is RP1, a genetically engineered version of HSV-1 developed by biotech firm Replimune. This “oncolytic virus” is not just designed to destroy cancer cells—it’s also built to activate the immune system in powerful ways.

When injected directly into a tumor, RP1 replicates within the cancer cells until they rupture. This process releases tumor-specific antigens that act like distress beacons for the immune system. White blood cells—including T cells and natural killer cells—rally to the site and begin targeting similar cancer cells throughout the body, even those that the virus itself never reached.

But RP1 doesn’t stop there. It’s been engineered to produce GM-CSF, a signaling protein that attracts and activates immune cells. This helps transform tumors that once hid from the immune system (“cold” tumors) into highly visible targets (“hot” tumors). Moreover, RP1 is designed to work in combination with drugs like nivolumab, a checkpoint inhibitor that unblocks the immune response. Together, these therapies form a one-two punch—RP1 reveals the cancer, and nivolumab helps the immune system strike without hesitation.

The results? In clinical trials, RP1 has demonstrated that not only injected tumors shrink, but uninjected ones do too—a sign of systemic immune activation.

Evidence from the Front Lines: Clinical Trial Success

For patients with late-stage melanoma—many of whom had exhausted every available treatment—the results of the RP1 trials offer a new lease on life.

In the Phase 1/2 IGNYTE trial, led by Keck Medicine of USC, researchers enrolled 140 patients across the globe. All participants had advanced melanoma that was either resistant to or had stopped responding to existing immunotherapies. When treated with a combination of RP1 and nivolumab, roughly one-third of patients experienced a tumor reduction of at least 30%. Astonishingly, nearly one in six saw complete tumor regression.

Patients received direct tumor injections of RP1 every two weeks for up to eight cycles, alongside regular intravenous infusions of nivolumab. Those showing strong responses transitioned to maintenance nivolumab for up to two years. Notably, even tumors that were not injected with RP1 responded to the therapy—an indication that the immune system was fighting back system-wide.

Just as important as the efficacy is the safety profile. Unlike chemotherapy or radiation, which can damage healthy tissue and cause debilitating side effects, RP1 therapy has been well-tolerated. Side effects have been mild, and because HSV-1 is so well-understood, existing antiviral drugs provide an effective safety net.

FDA Fast Track and the Road Ahead

The compelling results from these trials have captured the attention of regulators. In January 2025, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted priority review status to the RP1 and nivolumab combination for advanced melanoma—a move that could accelerate approval and access if ongoing trials continue to yield positive outcomes.

The ongoing Phase 3 IGNYTE-3 trial will enroll over 400 patients worldwide and aims to provide definitive answers about long-term survival, recurrence rates, and broader applicability. The outcomes of this trial will determine whether RP1 moves from promising experimental treatment to frontline therapy.

Expanding the Possibilities: Beyond Melanoma

While the spotlight is currently on melanoma, RP1 and similar virus-based treatments are not limited to skin cancer. Oncolytic viruses are being studied in a wide range of cancers, including lung, breast, pancreatic, ovarian, and brain tumors—many of which are notoriously hard to treat due to late detection and resistance to existing therapies.

What makes these viral therapies so adaptable is their ability to be customized. Scientists can engineer viruses to express specific proteins that tailor the immune response, making them versatile tools in personalized medicine. Additionally, newer generations of these viruses are being designed to circulate through the bloodstream rather than requiring direct injection, potentially allowing them to reach deep or inaccessible tumors.

A separate study involving Talimogene laherparepvec (T-VEC)—another genetically engineered herpes virus—has shown promise when used before surgery in patients with operable melanoma. This approach, known as neoadjuvant therapy, significantly reduced the rate of cancer recurrence post-surgery, suggesting that early immune activation may play a crucial role in long-term disease control.

Challenges and the Path Forward

Of course, virus-based therapies are not without hurdles. Determining which patients are most likely to benefit, optimizing combinations with other treatments, and improving delivery mechanisms remain active areas of research. There are also logistical challenges with intratumoral injections, though new methods are being explored to address this limitation.

Nevertheless, the growing momentum is unmistakable. Oncolytic virotherapy is increasingly being recognized as a foundational pillar in cancer treatment—complementing, rather than replacing, surgery, radiation, and systemic drugs. It’s a testament to how far the field of immunotherapy has come—and how much further it can go.

A Future Built on Viral Innovation

The success of RP1 is more than just a promising development in melanoma treatment; it represents a broader evolution in how we think about disease and healing. In a world still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic, public understanding of viruses has shifted. We now recognize that viruses, when properly understood and reengineered, can serve not only as threats—but as tools for survival.

With advancements in gene editing, viral engineering, and immunotherapy converging, the next generation of cancer treatments may come not from chemical labs, but from biology itself. Already, researchers are exploring combinations with CAR-T cell therapy, BRAF inhibitors, and mRNA platforms, aiming to create multi-layered attacks on even the most stubborn tumors.

What was once unthinkable is now becoming routine: using the very agents of disease to wage war on one of humanity’s deadliest foes.

News in the same category

Former NASA boss makes heartbreaking admission about the future of US space travel

Why You Should Disconnect Your WiFi at Night And Sleep With Your Phone on Airplane Mode in Another Room

The Heartbreaking Fate Of ‘Little Albert’: Child Subject Of Historic Study Died At Just Six

Farmer Plants 1,000 Oak Trees to Create Memorial for Late Wife

TV Star Claps Back at Trolls Over Her Māori Face Tattoo

Insane amount of money viral 'Storm Area 51' stunt cost the US military

Scientists explain 'puzzling blob' heading straight for New York City that's hidden 200 kilometers below our feet

Inside the Life of Australia’s Largest Clan: The Bonell Family

Guy Mocked for Dating 252-lb Woman

Scientists Just Discovered an “Off Switch” for Cholesterol And It Could Save Millions of Lives

Free download offered to PlayStation gamers as way to 'make amends'

CelebrityTop FBI Official Makes Chilling Claim About Epstein Investigation

Hacker with 30 years experience reveals the one thing we need to be worried about in the future

Man who spent 10,000 Bitcoin on two pizzas in 2010 could've been eye-wateringly well off today

T3rrifying Moment Killer Orca Approached Viewing Window Holding Dead SeaWorld Trainer

Couple with Down Syndrome Choose to Have Children, Sparking Debate

World's Oldest Newborn: Baby Born After Being Frozen for 30 Years

The embryo the Pierces adopted was originally created through in vitro fertilization (IVF) back in 1994, making it older than many of today’s prospective parents themselves, according to MIT Technology Review.

Study Shows Men Are Twice as Likely to Die from ‘Broken Heart Syndrome’ Than Women – Here’s Why

News Post

A Long Story: A Gift from the Hearts of Students.

Beekeeper Sets Bees Loose on Police That Pulled Him Over for Traffic Stop

Bolo’s Big Day—And the Forever Home He Never Saw Coming.

I Thought I Was Just Buying Shawarma and Coffee for a Homeless Man — But the Note He Slipped Me Turned My Entire Life Upside Down

Evidence-Based Health Benefits of Honey (Raw, Pure, Natural) + Turmeric Golden Honey Recipe

My Own Daughter Robbed Me of $50,000 to Buy a New House — But My Adopted Daughter Made Her Regret It

The ‘World’s D3adliest Food’ K!lls 200 People Annually — Yet 500 Million Still Can’t Resist It

Every year, this claims over 200 lives worldwide, yet nearly half a billion people still rely on it as a daily food source. Experts warn that without proper preparation, this staple crop can turn d:eadly due to its natural cyanide content.

Cancer Is Painless At First, But If You See These 8 Signs When Going To The Bathroom, You Should Go For An Early Check-Up

Changes in bowel movements can sometimes be an early red flag for colon cancer, even when other symptoms seem absent. Understanding what’s normal — and what isn’t — could make all the difference in getting timely help.

The Hidden Meaning Behind Women's Leg-crossing — It’s More Than Just Comfort

The Hidden Meaning Behind Leg-Crossing — Body Language Secrets, Health Risks, and What It Really Says About You.

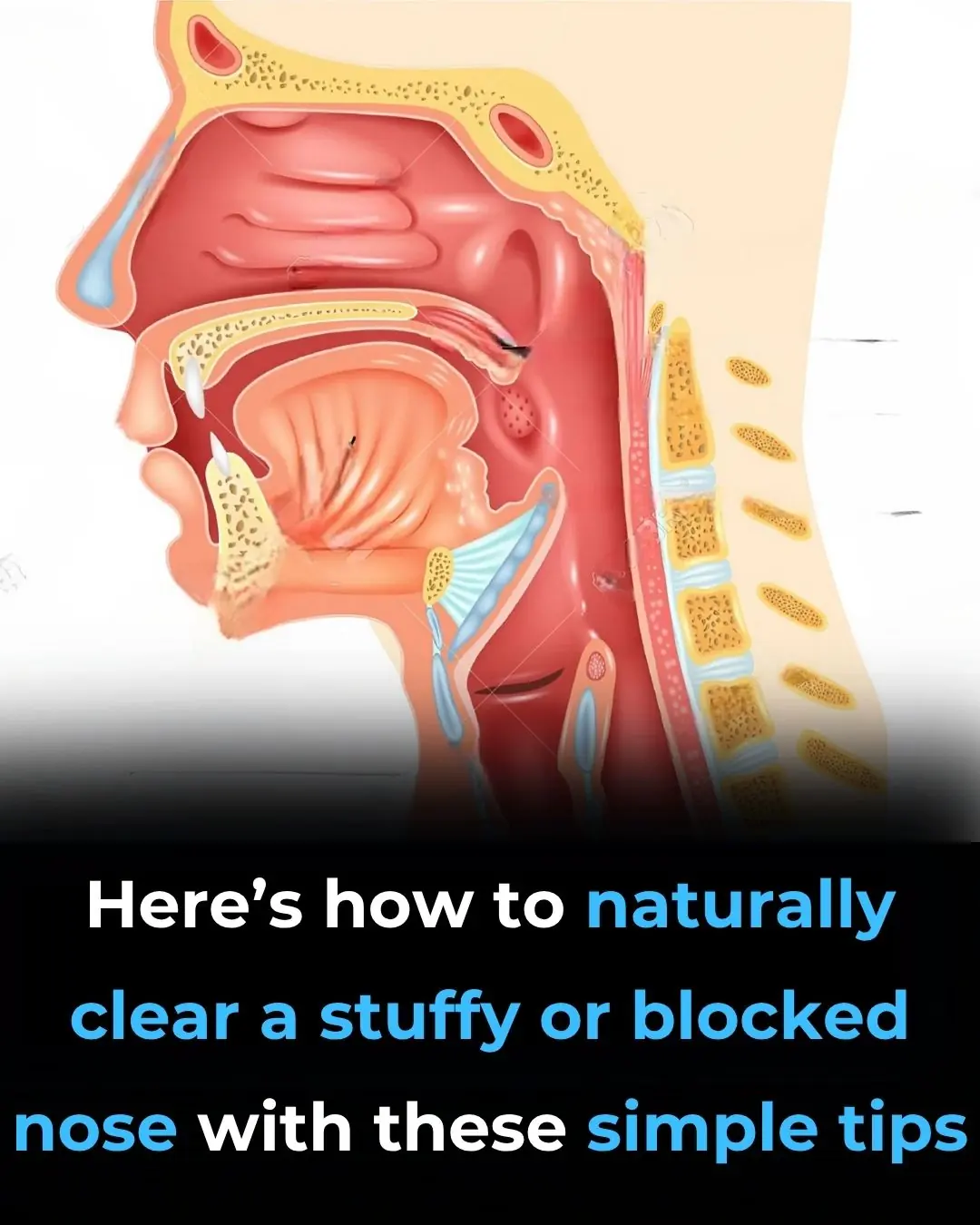

Home Remedies for Blocked and Stuffy Nose

Woman Reveals the Sh0cking Fantasy Over 50% of Married People Secretly Admit To Having

Over half of married people admit to secretly fantasizing about an ex — a habit experts say can trigger emotional detachment and strain current relationships. While revisiting old memories may feel harmless, psychologists warn it could signal deeper iss

Say Goodbye to Fillings Soon? Scientists Just Grew Real Human Teeth In a Lab That Could Replace Fillings Forever

What if your body could suddenly remember an ability it lost thousands of years ago - the power to grow an entirely new tooth?

The Secret Behind the Small Metal Bump on Scissors Everyone Missed

People Are Stunned To Discover The Real Purpose of the Small Metal Bump Between Scissor Handles — And It’s More Useful Than You Think.

Doctors Warn 3 “Don’ts” After Meals—And 4 “Don’ts” Before Bed To Prevent Stroke At Any Age

Up to 80% of strokes can be prevented, and the key lies in small daily habits — especially right after meals and before bedtime. Science now reveals 3 post-meal and 4 pre-bed “don’ts” that can protect your brain, heart, and long-term health at any

The Chilling Truth About Why No Human Remains Were Found in the Titanic Wreck

More than 110 years after the Titanic sank, scientists have revealed the chilling reason no human remains were ever found in its wreckage. Resting 12,000 feet below the Atlantic, the site tells a silent story of how nature claimed the victims in its own w

Symptoms of Chikungunya virus revealed as China takes 'COVID measures' after reporting 7,000 cases

China is on high alert after more than 7,000 Chikungunya virus cases were reported across 13 cities in Guangdong, prompting swift containment measures. Unlike COVID-19, this mosquito-borne disease spreads through bites, but its painful symptoms and rapid

Foamy Urine: Here’s Why You Have Bubbles in Your Urine

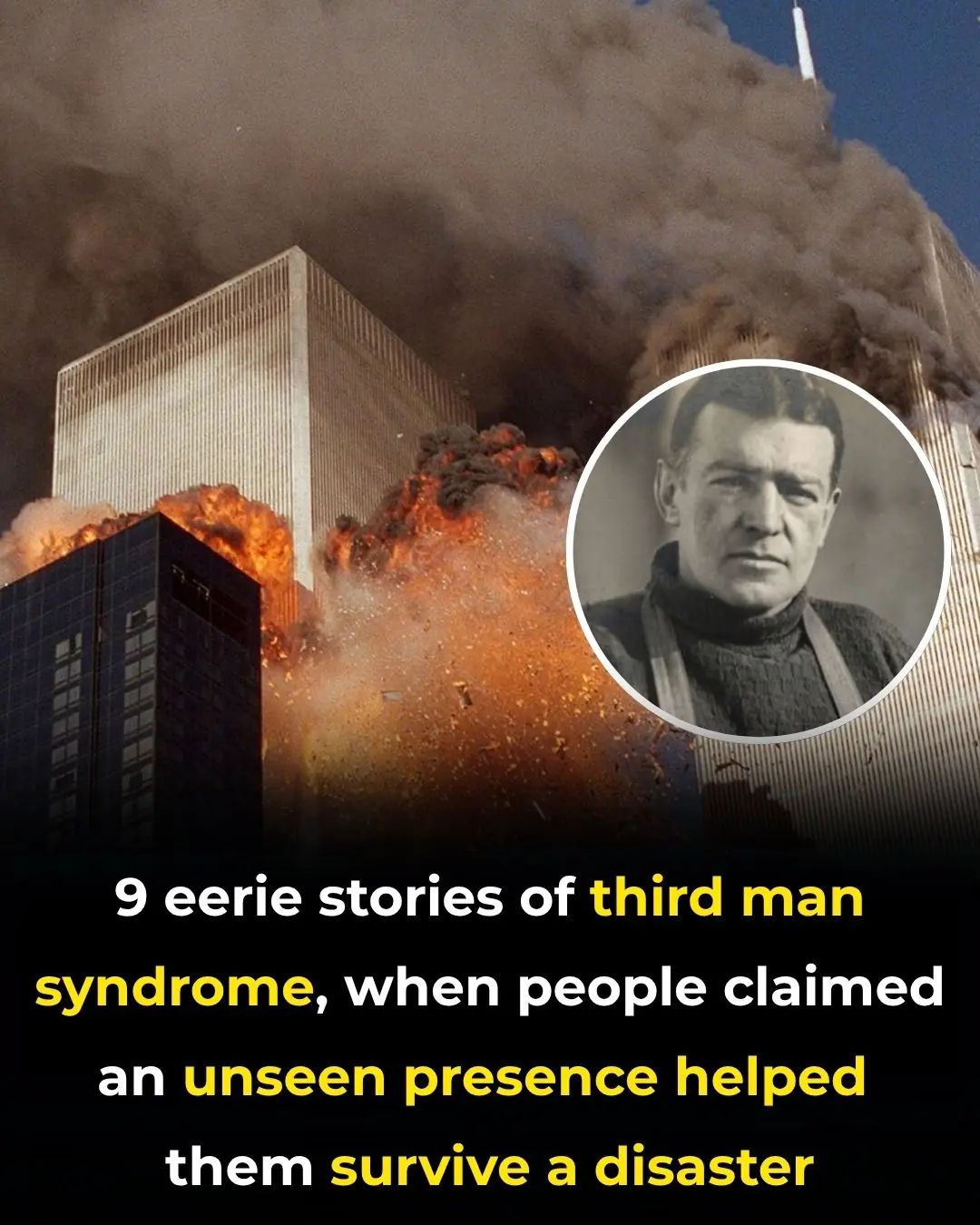

9 Chilling Stories of Third Man Syndrome: When an Unseen Presence Aided Survival in Disasters