New Study Finds Eating More Than 1 Egg Per Week Cuts Alzheimer’s Risk by 47%

Breakfast tables hold a simple secret that might protect aging brains

Scientists have uncovered a surprisingly modest dietary habit that could offer meaningful protection against cognitive decline. Over the course of nearly seven years, researchers followed more than 1,000 older adults, documenting their eating patterns and tracking who went on to develop dementia. Their findings point to a common household food that may guard the brain against Alzheimer’s disease — one that sits quietly in almost every refrigerator.

Just one egg per week. Such a small change, yet the data revealed something striking: participants who ate at least one egg weekly had an approximately 47% lower risk of developing Alzheimer’s dementia compared with those who consumed eggs less than once a month. Even more compelling, brain autopsies conducted after death confirmed the biological evidence — these individuals exhibited fewer amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the signature pathological hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease.

The study, part of the Rush Memory and Aging Project, challenges decades of traditional nutrition guidance that once warned against egg consumption because of cholesterol concerns. Instead, the new evidence indicates that regular egg intake may actively support cognitive resilience and slow neurodegenerative processes in aging adults.

Unlike costly interventions such as pharmaceutical treatments or specialized supplements, eggs are inexpensive, widely available, and easy to prepare. If replicated by future research, this simple dietary habit could help reshape public health recommendations for maintaining brain health well into old age.

The Research Behind the Numbers

The Rush Memory and Aging Project began collecting dietary data in 2004 using detailed food frequency questionnaires (FFQs). A total of 1,064 participants provided information about their typical food and supplement intake over the previous year. The assessment, adapted from Harvard’s semiquantitative FFQ, covered more than 137 distinct food items to capture nuanced eating habits.

This specific analysis focused on the relationship between egg consumption and the development of Alzheimer’s dementia. Participants were observed from their initial dietary assessment until either clinical diagnosis of dementia or death. Sophisticated statistical models were used to control for potential confounders such as age, education, activity level, body mass index, and vascular risk factors, ensuring the results reflected a true association rather than coincidence.

1,024 Seniors Tracked for Nearly Seven Years

After excluding individuals with incomplete data or pre-existing dementia, 1,024 older adults remained for the final analysis. The average age was 81.4 years, and nearly three-quarters (74.8%) were women. Importantly, many carried the ApoE-ε4 genetic variant, a known risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

Participants were monitored for an average of 6.7 years. During that time, 280 individuals (27.3%) received a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia. Of those who passed away, 578 donated their brains for autopsy, providing invaluable confirmation of the underlying disease processes.

Egg intake was categorized into five frequency levels:

-

Less than once monthly

-

1–3 times monthly

-

Once weekly

-

2–4 times weekly

-

5 or more times weekly

Because few participants fell into the highest consumption groups, researchers combined the top two categories into “two or more eggs weekly.” Baseline characteristics, such as age, body mass index, education, and physical activity, differed across groups, but statistical adjustments accounted for these variations.

The 47% Risk Reduction: Breaking Down What Researchers Found

The adjusted results were both clear and compelling. Compared to those who ate eggs less than once a month, participants consuming one egg per week had a hazard ratio of 0.53, meaning their risk of developing Alzheimer’s was nearly 47% lower. Those eating two or more eggs weekly showed an identical hazard ratio.

Confidence intervals — 0.34 to 0.83 for one egg weekly and 0.35 to 0.81 for two or more — confirmed the findings were statistically significant, not random fluctuations. The protective association held strong even after adjusting for multiple variables including age, gender, education, BMI, smoking, exercise, cognitive activity, vascular factors, and the consumption of other brain-healthy foods like leafy greens and seafood.

Even partially adjusted models (considering only age, gender, and education) produced similar results, reinforcing the robustness of the relationship between egg consumption and reduced Alzheimer’s risk.

Brain Autopsies Tell the Real Story: Less Plaque, Fewer Tangles

While clinical diagnoses rely on cognitive testing and observation, autopsy data provides direct biological proof. Among the 578 participants who donated their brains, pathologists analyzed tissues for two key Alzheimer’s markers: amyloid-beta plaques and tau protein tangles.

Those who ate one or more eggs weekly had a hazard ratio of 0.51 for pathological Alzheimer’s disease. Participants consuming two or more eggs weekly had a hazard ratio of 0.62, both statistically significant after full adjustment. In simpler terms, the brains of frequent egg eaters contained less structural evidence of Alzheimer’s pathology.

Interestingly, not every clinical diagnosis matched autopsy findings. Among 372 participants without clinical dementia, 55.9% still showed underlying Alzheimer’s pathology, while 17.9% of those diagnosed clinically had no pathological confirmation. Yet, egg intake consistently predicted lower rates of both clinical and biological Alzheimer’s indicators, suggesting it may delay or prevent the underlying disease process itself.

Why Eggs Protect Your Brain

To understand why eggs may have this effect, researchers performed mediation analysis to determine whether choline, a nutrient abundant in eggs, played a central role. They found that 39% of the protective benefit could be explained by higher dietary choline intake.

Choline is essential for synthesizing acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that facilitates learning and memory. In Alzheimer’s disease, acetylcholine-producing neurons are among the first to deteriorate. By ensuring adequate choline supply, eggs may help preserve cholinergic function and slow this neuronal loss.

Choline also contributes to the formation of phospholipids — structural components of cell membranes that maintain neuronal integrity. Without enough choline, brain cells lose membrane stability, communication efficiency, and resilience against stress.

What Makes Eggs a Brain Health Superfood

Egg yolks contain a synergistic mix of nutrients critical for cognitive health:

-

Choline, the brain’s building block and memory protector

-

Omega-3 fatty acids (DHA), essential for neuronal structure and signaling

-

Lutein, an antioxidant that protects brain tissue from oxidative stress

DHA-enriched eggs, for example, deliver fatty acids directly incorporated into brain cell membranes, enhancing fluidity and communication. Lutein, meanwhile, accumulates in brain tissue, where it reduces oxidative damage and inflammation. Together, these compounds form a neuroprotective network that supports long-term cognitive performance.

Research also suggests choline enhances the transport of omega-3s across the blood-brain barrier, demonstrating that these nutrients may act synergistically rather than independently.

From Breakfast Plate to Brain Protection: How the Mechanism Works

After consumption, digestive enzymes release choline and phospholipids in the small intestine, which are then rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. The liver processes these molecules, converting them into phosphatidylcholine and related compounds that circulate back into the blood.

Specialized transporters in the blood-brain barrier recognize these molecules and allow them to enter brain tissue. Inside neurons, choline supports the synthesis of acetylcholine, contributes to membrane repair, and regulates gene expression through methylation reactions.

Alzheimer’s pathology disrupts this delicate system, creating a feedback loop of neuronal loss and reduced acetylcholine. By providing consistent dietary choline, eggs may help stabilize neurotransmission and maintain cognitive performance even as aging progresses.

The Dose Matters: More Eggs, More Protection?

Interestingly, the study found no additional benefit beyond the one-egg-per-week threshold. Both the one-egg and two-or-more-egg groups showed identical risk reductions. This pattern suggests a threshold effect — modest intake may provide maximal benefit, while higher consumption yields diminishing returns.

However, because relatively few participants ate multiple eggs weekly, larger studies are needed to confirm whether more frequent consumption could offer additional advantages.

What This Means for Your Diet Today

For older adults, these findings point toward a simple, low-cost intervention: eating at least one egg per week. Preparation methods matter; boiled, poached, or lightly scrambled eggs made with minimal added fat align best with overall cardiovascular health.

Those with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or elevated cholesterol should still consult healthcare providers before changing their diets, as individual metabolic responses vary. Importantly, eggs should complement, not replace, other nutrient-rich foods like vegetables, fruits, fish, and whole grains — all shown to contribute to cognitive protection in Mediterranean-style diets.

The Potential of Eggs in Alzheimer’s Prevention

This study represents an important step in re-evaluating dietary guidelines that have long vilified eggs. With strong evidence linking moderate egg consumption to improved brain health, scientists are beginning to view them not as a cholesterol risk, but as a nutritional ally in cognitive longevity.

For aging adults, a single egg each week may be more than breakfast — it could be a neuroprotective habit that sustains memory, focus, and independence. While further research is essential to determine long-term and age-specific effects, these findings highlight a profound truth: sometimes, the simplest foods on our plates hold the most powerful defenses for our brains.

So next time you sit down to breakfast, remember — that humble egg might just be a small but mighty safeguard for your mind in the years ahead.

News in the same category

How Denmark Is Redefining Childhood in the Digital Age

4 things you shouldn't keep

The Hidden Meaning Behind Tongue Piercings Most People Don’t Know

Scientists Create Revolutionary “Superwood” Stronger Than Steel and Completely Fireproof

The Wondiwoi Tree Kangaroo Returns After Nearly a Century of Silence

Why do many men love married women more than single women?

5+ Things That Men Actually Notice About Women

This Is the Most Attractive Hobby a Man Can Have, According to Women

Pick The Underwear You Would Wear To Reveal What Kind Of Woman You Are

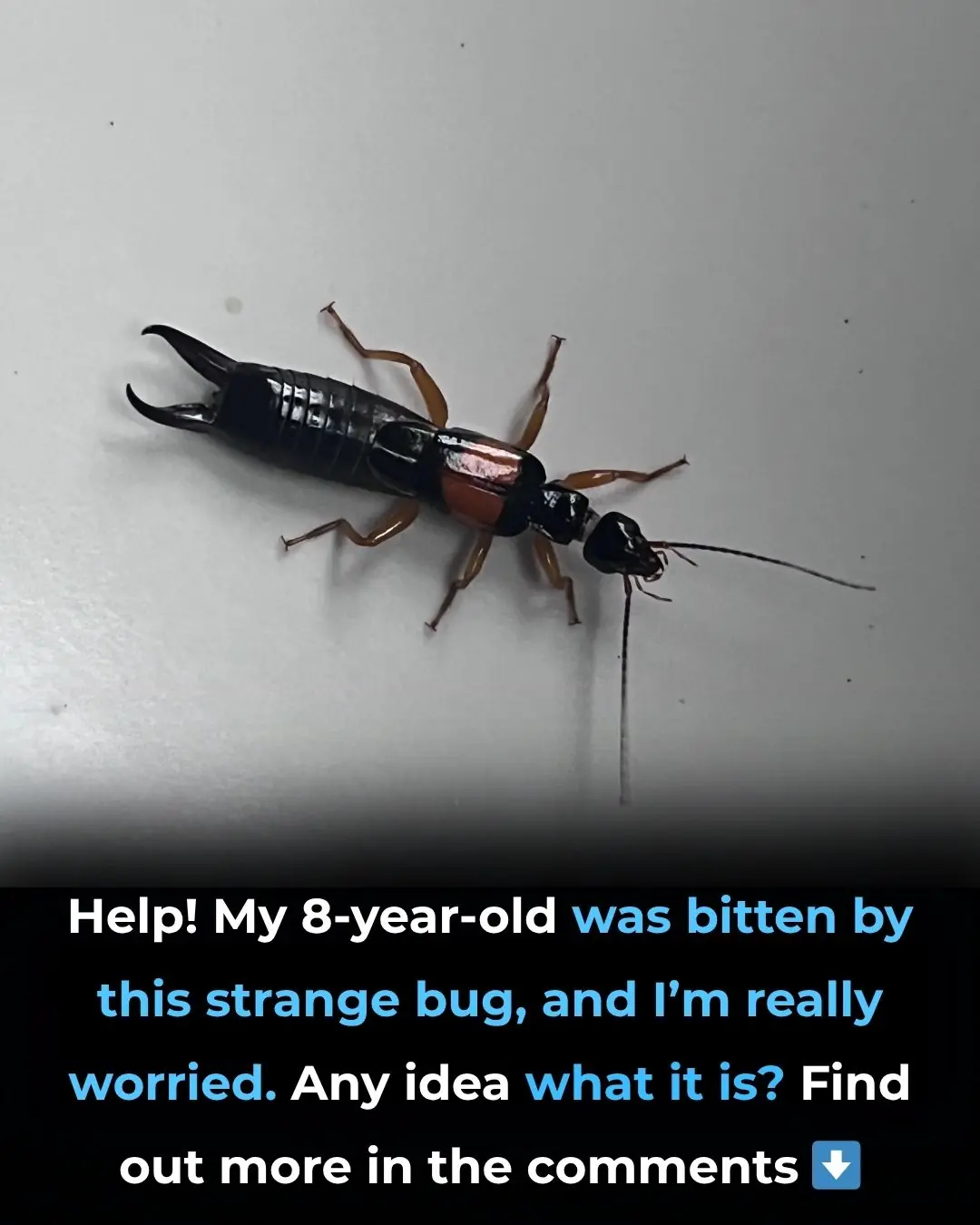

What to Do If Your Child Is Bitten by a Strange Bug

If you're caught Googling these four words Police may show up at your house

Fascinating animation reveals exactly how gas pumps know when to stop pouring gas

Elon Musk's Starlink satellites could be falling out of the sky

Expert issues chilling warning on Elon Musk's robots as billionaire plans to put them on Mars

Jeff Bezos sent a secret tourist into space and their identity is set to be revealed

Super typhoon set to send shockwaves through the US is just days away

Moon Meets Mars: A Dazzling Celestial Encounter on October 11, 2025

All DNA and RNA Bases Found in Meteorites: Life’s Origins May Be Cosmic

News Post

The #1 Enemy of Your Thyroid: Stop Eating This Food Immediately!

7 Warning Signs of a Heart Attack You Can Spot Up to a Month Before—And the One Deadly Sign You Must Never Ignore

This Food Helps Activate Your Body’s Stem Cells So It Can Repair Itself Naturally

These 4 Herbs Can Protect Your Brain From Alzheimer’s, Depression, Anxiety & Much More

The Animal You See First Reveals Your Anger Trigger

Hidden Signs Constipation Is Affecting Your Whole Body

6 things mice are very afraid of, just put them in the house and the mice will run away

Put a handful of salt in the refrigerator: A golden use that every home needs

5 tips to keep your bathroom smelling fresh all week without having to clean it

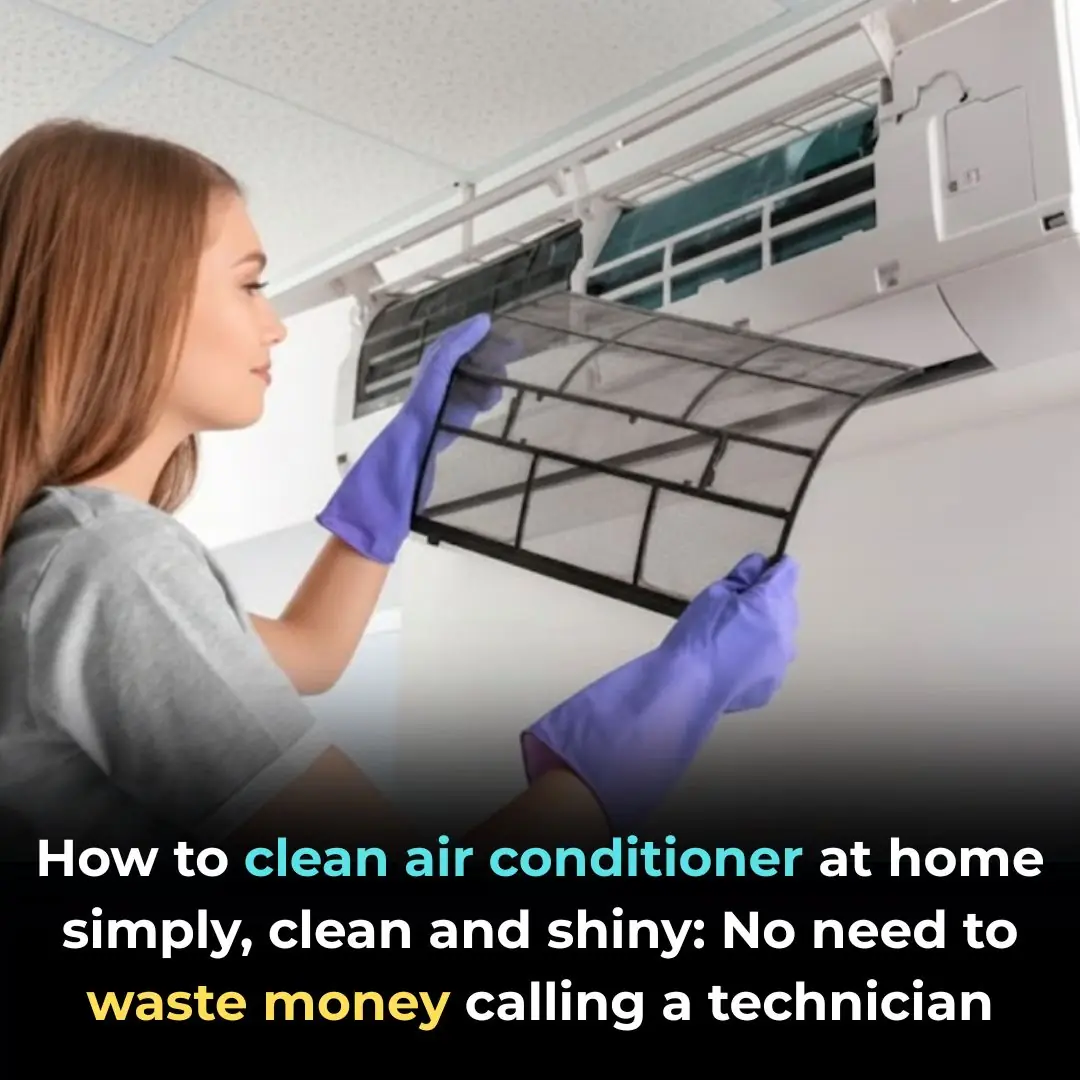

How to clean air conditioner at home simply, clean and shiny: No need to waste money calling a technician

Put a drop of essential oil on clothes while soaking: "Special" use, not everyone knows how to apply it

Don't throw away rice water, keep it for these 6 "magical" things, save millions every year

Tips for conditioning hair with black vinegar, both economical and helps reduce hair loss and grow faster

The whole tree is a treasure, many people only eat the fruit but the flowers are the specialty, cooked into soup to make a super nutritious dish.

How Denmark Is Redefining Childhood in the Digital Age

Giving Back: 6-Year-Old Feeds Homeless For Her Birthday

This 4-Year-Old Honorary Librarian Has to be the Cutest and Most Well Read Kid Ever

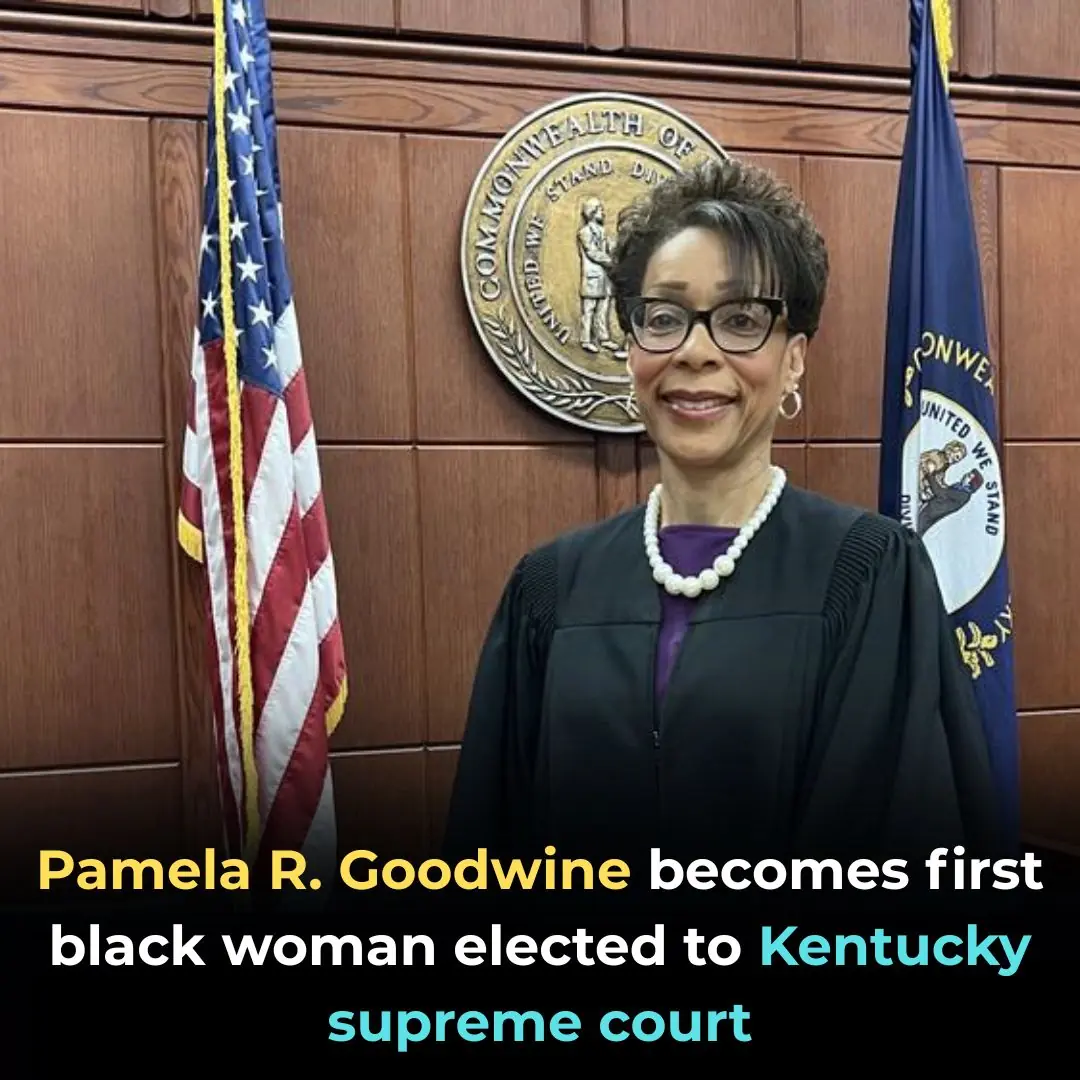

Pamela R. Goodwine Becomes First Black Woman Elected to Kentucky Supreme Court