Gene therapy in children with AIPL1-associated severe retinal dystrophy: an open-label, first-in-human interventional study

Introduction

Methods

Study design

Participants

Procedures

News in the same category

The First Communication Between Two Humans While Dreaming Has Been Achieved – This Is How It Works

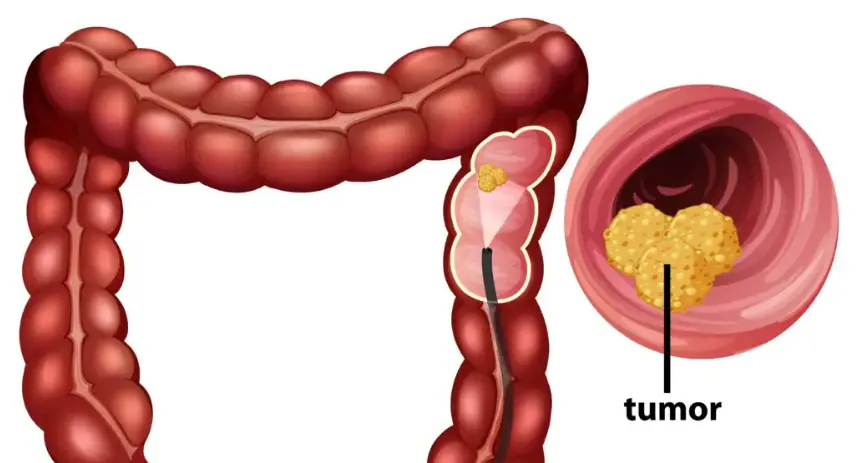

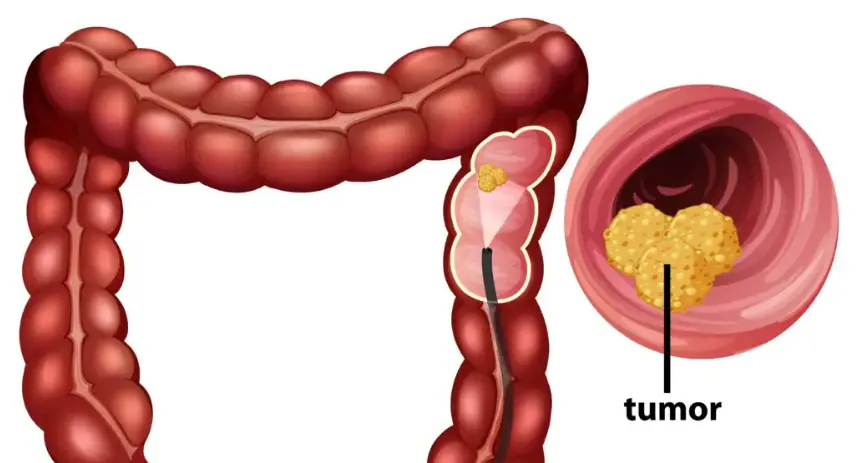

How Your Bowel Movements Reveal Clues About Colon Cancer

20 Cancer Signs People Ignore Until It’s Too Late

Surprising Health Benefits of Chai Spices

Health Benefits of Raw Garlic, a Daily Superfood

8 Early Warning Signs of Nutrient Deficiency Written All over Your Body

Neurologist reveals the single scariest thing she sees people doing to their brains

Association of Birth During the COVID-19 Pandemic With Neurodevelopmental Status at 6 Months in Infants With and Without In Utero Exposure to Maternal SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Discover the Health Benefits of Kyllinga brevifolia

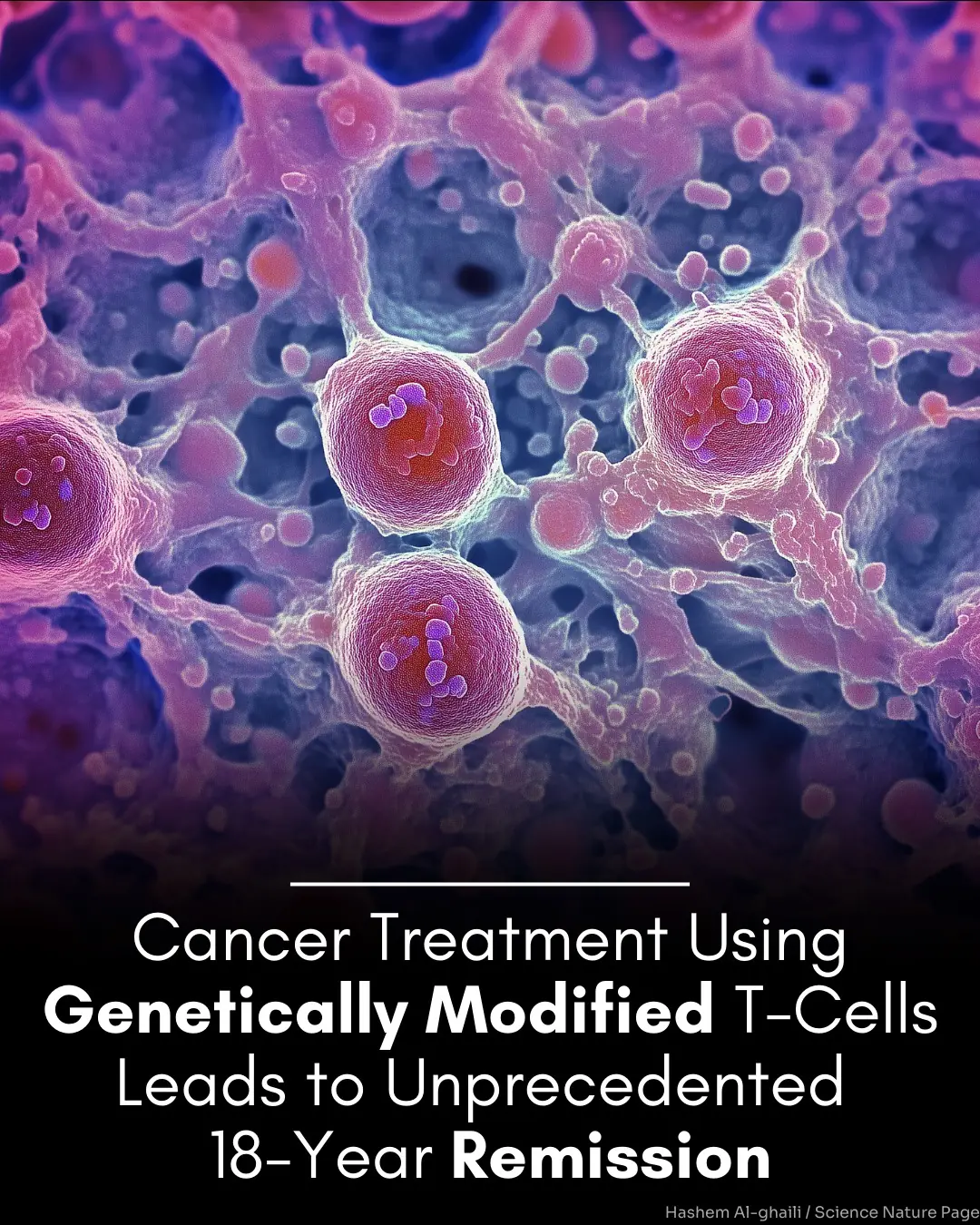

Long-term outcomes of GD2-directed CAR-T cell therapy in patients with neuroblastoma

Top 10 Most Deadly Habits That Seriously Damage Your Kidneys Top 10 Most Deadly Habits That Seriously Damage Your Kidneys

If You Have a Stabbing Pain In Your Rear, Here’s What It Could Mean

What Happens To Your Body When You Eat Cottage Cheese Every Day

10 Ways to Help Reduce Your Colon Cancer Risk

Revitalize Your Feet: The Ultimate Lemon and Baking Soda Foot Soak

Specialists Point Out Phrases That Might Suggest Dementia

Benefits of Lemon Water: What’s Myth and What’s Fact?

What to Expect After Gallbladder Surgery: Side Effects and Dietary Tips

News Post

I Grew Suspicious of My Husband After Giving Birth – Then I Accidentally Saw Why on the Baby Monitor

When Elodie's husband, Owen, starts acting distant after the birth of their son, she fears the worst. Sleepless nights and creeping doubts push her to uncover the truth, only to find something she never expected.

Psoas Muscle Pain Relief: How to Unlock the ‘Muscle of Your Soul’

My Husband's Family Asked Me to Be a Surrogate – but I Had No Idea Who the Baby Was Really For

When Jessica's husband, James, asks her to be a surrogate for his brother's fiancée, she agrees against her better judgment. Yet, as the pregnancy progresses, her doubts grow. The fiancée remains unreachable, the details feel off, and when Jessica final

My Landlord Tossed My Stuff in the Trash and Kicked Me Out – the Next Day, She Was Dragging Her Own Belongings to the Curb

When my landlord Amanda tossed my belongings in the trash and locked me out without warning, I thought I had lost everything. But just 24 hours later, I watched her dragging her own furniture to the curb as she faced eviction herself. That was karma. Pure

7 Surprising Reasons to Let Your Radishes Go to Seed and Enjoy Radish Pods

Common Milkweed (Asclepias syriaca): 7 Essential Key Benefits

Sumac Tree Benefits – A Powerful Medicinal and Culinary Plant

Boiled Orange Peels and Cloves: A Natural Home Remedy with Numerous Benefits

Yes, Mosquitoes Can Tell Your Blood Type

A Poor Boy's Life Changes After He Pulls an Old, Rusty Chain Sticking Out of the Sand on a Remote Beach

The rusted chain jutting from the sand seemed worthless to everyone else, but to 13-year-old Adam, it promised an escape from poverty. He couldn't have known that tugging on those corroded links would teach him something far more valuable than gold or sil

Yarroway: Unveiling the Healing Power : A Comprehensive Guide

Ancient Onion Tea Recipe for Blood and Liver Detox

The First Communication Between Two Humans While Dreaming Has Been Achieved – This Is How It Works

I Gave Shelter to a Homeless Woman in My Garage – Two Days Later, I Looked Inside and Cried, 'Oh God! What Is This?!'

When Henry offers shelter to a homeless woman, he doesn't expect much, just a quiet act of kindness. But two days later, his garage is transformed, and Dorothy is nothing like she seemed. As her tragic past unravels, Henry realizes this isn't just about s

My Husband's Sister Moved in After Her Divorce — One Day I Came Home to Find My Stuff Thrown Out

I Saw a Homeless Man Handing Out Two Bags of Money to Kids on the Street and Immediately Called the Cops

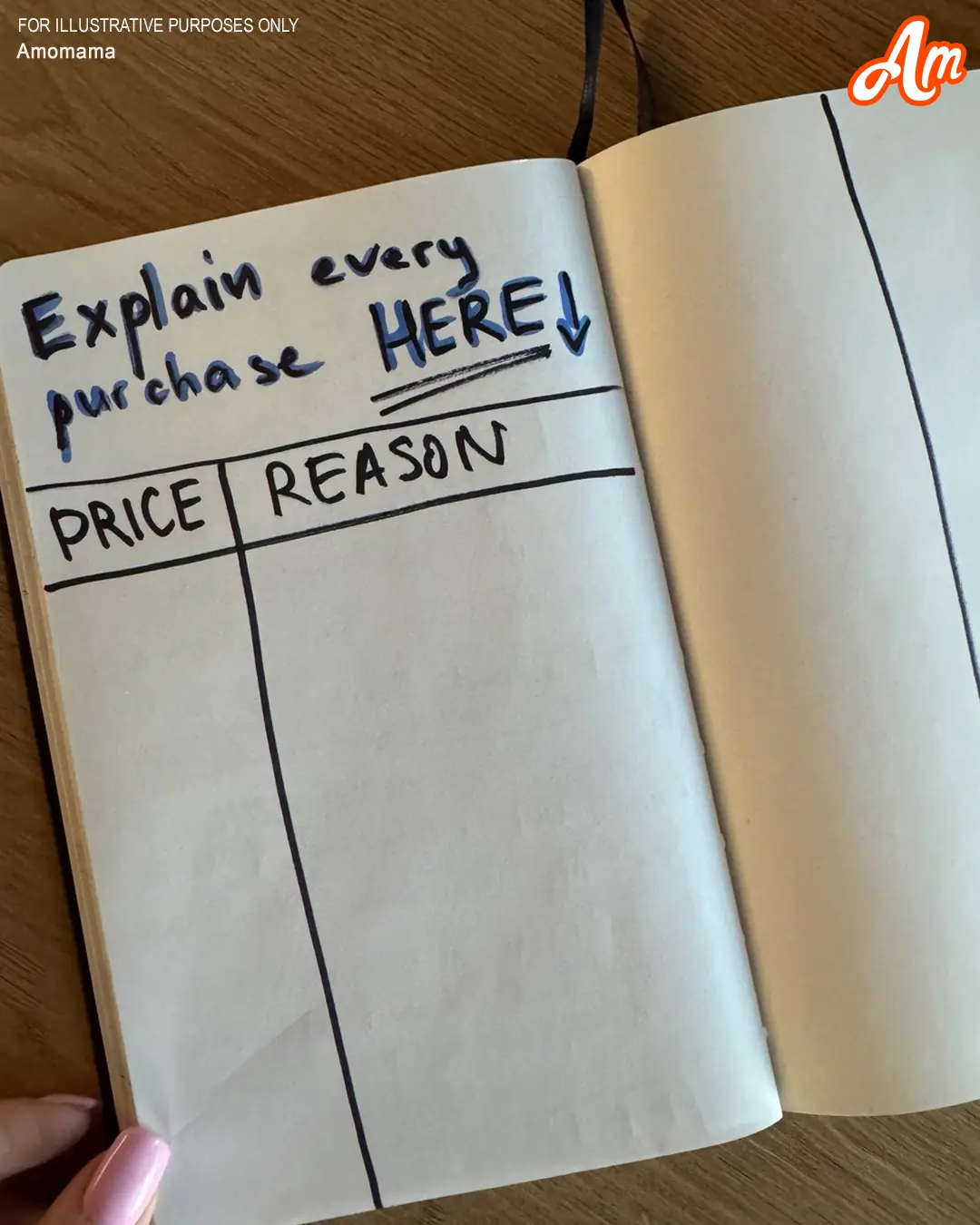

My Husband Made Me Justify Every Penny I Spent with Explanatory Notes — So I Taught Him a Lesson He'd Never Forget

Drinking One Coconut a Day is Like Sipping the 'Elixir of Life'