Hawaii’s Million Mosquitoes a Week: A Bold Move to Save Endangered Birds

At first, the idea of releasing one million mosquitoes a week in Hawaii sounds alarming, but the truth behind this strategy is far more fascinating and, in fact, is part of a crucial conservation effort. This innovative approach is not about increasing the mosquito population, but rather about using them as part of a carefully planned effort to protect some of the world’s most endangered species—Hawaii’s native honeycreeper birds.

The Mosquitoes: How They Help, Not Harm

Here’s the key to understanding this unconventional plan: all the mosquitoes being released are male, and male mosquitoes do not bite. This is important because it means the release of these mosquitoes will not add to the nuisance or health risks typically associated with mosquitoes. Instead, these males are carrying a natural bacterium called Wolbachia, which is crucial in this conservation method.

When these male mosquitoes mate with wild female mosquitoes, the eggs they produce fail to hatch. This prevents the population of mosquitoes from growing, gradually causing the mosquito numbers to decline. The goal, therefore, is not to increase the mosquito population, but to reduce it by preventing the next generation of mosquitoes from being born.

Why This Is Vital for Hawaiian Birds

This mosquito release program is particularly critical in Hawaii, where native species, such as the honeycreeper birds, are facing extinction. These birds are being decimated by avian malaria, a disease transmitted by a non-native mosquito species that arrived in Hawaii in the 1800s. As global temperatures rise, mosquitoes are migrating to higher elevations in Hawaii’s mountain forests—the last remaining safe havens for these endangered birds.

Without intervention, these birds are at risk of disappearing forever. Conservationists and scientists have been working to stop the spread of avian malaria, and this mosquito release strategy is one of the most innovative ways to combat the disease and save the birds.

The Release Process: How It Works

Each week, 500,000 treated male mosquitoes are released on the islands of Maui and Kauai, totaling around 1 million mosquitoes being released into the wild. These mosquitoes are dropped over remote forest areas via helicopters and drones, which carry biodegradable pods containing the mosquitoes. These areas are difficult to access by ground crews, making the aerial delivery of mosquitoes an ideal solution.

This method has been used successfully in several countries around the world and is recognized by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for emergency use. It is not a form of genetic modification, but rather a natural method to reduce harmful mosquito populations and ultimately save endangered wildlife.

A Science-Backed Plan to Save Birds

This technique is not a wild experiment—it is a science-backed, carefully executed plan to save the Hawaiian honeycreeper and other native bird species. The use of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes has been proven effective in reducing mosquito populations and controlling diseases like avian malaria. As these treated mosquitoes mate with wild females, their offspring are no longer viable, effectively collapsing the mosquito population over time.

If left unchecked, the spread of avian malaria could lead to the extinction of several Hawaiian bird species. This mosquito release program, though unusual, is a last-resort effort that is essential for the survival of these birds.

What Does This Mean for Hawaii’s Future?

While the concept of releasing a million mosquitoes a week may initially seem alarming, it’s important to understand the context. These mosquitoes are specifically engineered to help combat the threat of avian malaria and protect the unique and rare wildlife of Hawaii. They are non-biting, disease-free, and are part of a well-researched and carefully monitored strategy to save some of the rarest birds on Earth.

The use of male mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia to reduce populations is a form of biological control, a method that has been used in other parts of the world with success. As temperatures rise and invasive species continue to threaten native ecosystems, this technique offers hope for protecting species that might otherwise be lost forever.

In conclusion, while the idea of Hawaii releasing a million mosquitoes a week may sound strange, it is part of a crucial plan to save the Hawaiian honeycreeper and other endangered bird species. By carefully managing the mosquito population, this innovative approach could be key to preserving Hawaii’s natural heritage and biodiversity for future generations.

News in the same category

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

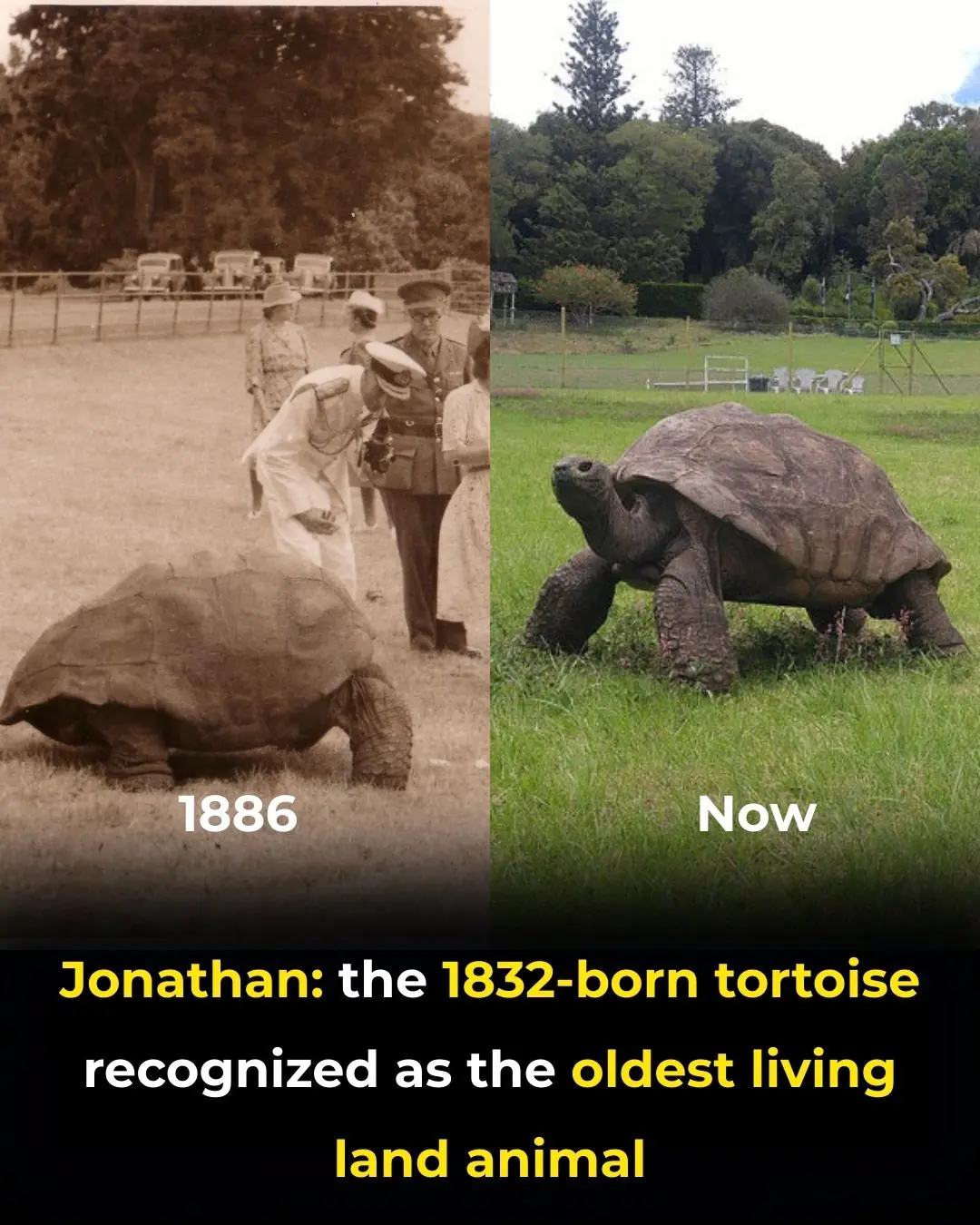

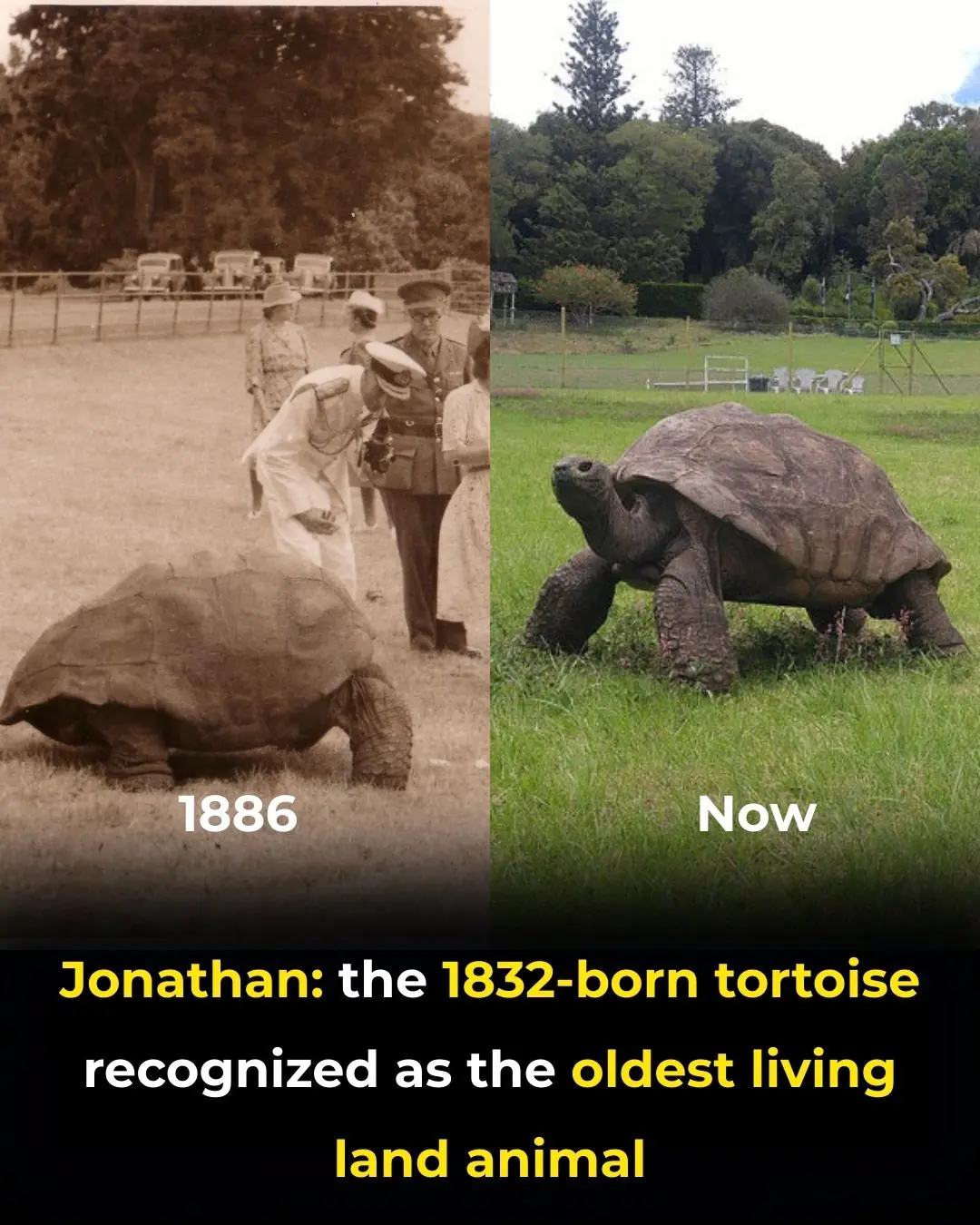

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy

Revolutionary Cancer Treatment Technique: Restoring Cancer Cells to Healthy States

The Critical Role of Sleep in Brain Health: How Sleep Deprivation Impairs Mental Clarity and Cognitive Function

Scientists Discover The Maximum Age a Human Can Live To

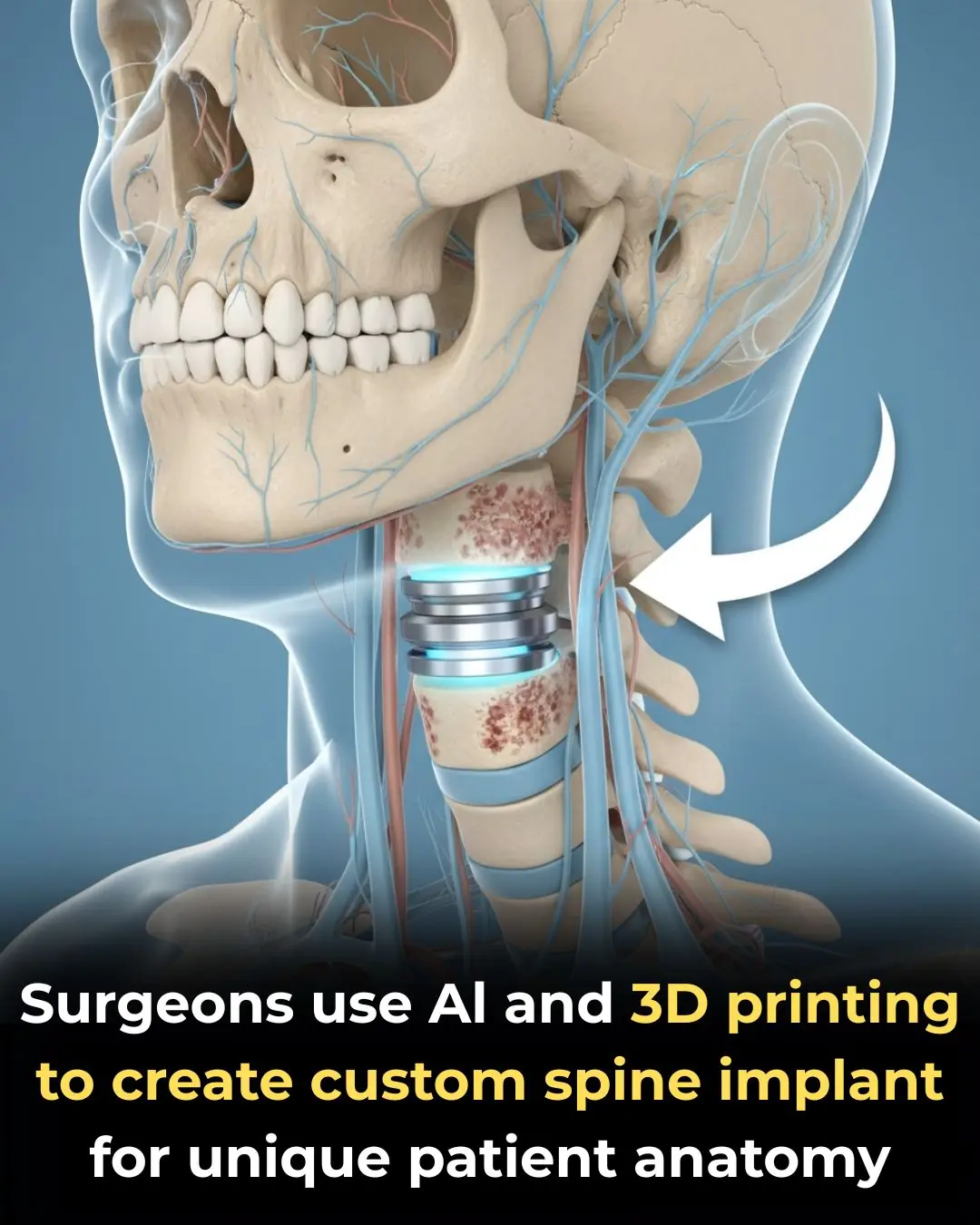

UC San Diego Health Performs World’s First Personalized Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery Using AI and 3D Printing

Could Your Blood Type Be Influencing How You Age

News Post

The Powerful Medicinal Benefits and Uses of Senna alata

The Ultimate Guide to Beetroot: Benefits, Uses, and Creative Ways to Enjoy It

Unveiling the Green Marvel: The Top Health Benefits of Common Mallow Leaves

What does it symbolize when a person who passed away appears in your dream

Fatty liver disease: 6 symptoms you need to know

Tiny Pumpkin Toadlet Discovered in Brazil's Atlantic Forest: A New Species of Vibrantly Colored Frog

Overview Energy's Bold Plan to Beam Power from Space to Earth Using Infrared Lasers

Japan’s Ghost Homes Crisis: 9 Million Vacant Houses Amid a Shrinking Population

Japan’s Traditional Tree-Saving Method: The Beautiful and Thoughtful Practice of Nemawashi

Swedish Billionaire Buys Logging Company to Save Amazon Rainforest

The Farmer Who Cut Off His Own Finger After a Snake Bite: A Tale of Panic and Misinformation

Meet Jonathan: The 193-Year-Old Tortoise Who Has Witnessed Three Centuries

Scientists Achieve Historic Breakthrough by Removing HIV DNA from Human Cells, Paving the Way for a Potential Cure

Belgium’s “Pay What You Can” Markets: Redefining Access to Fresh Food with Community and Solidarity

China's Betavolt Unveils Coin-Sized Nuclear Battery with a Potential 100-Year Lifespan

Japan’s Morning Coffee Kiosks: A Quiet Ritual for a Peaceful Start to the Day

13-Year-Old Boy From Nevada Buys His Single Mother a Car Through Hard Work and Dedication

ReTuna: The World’s First Shopping Mall Built on Repair, Reuse, and the Circular Economy