This 4,500-Year-Old Scroll May Have the Answer to Who Built the Pyramids

For centuries, the Great Pyramid of Giza has stood as an enigma—a monument so perfectly engineered that even modern architects marvel at its precision. How did an ancient civilization, without cranes or steel tools, construct a 481-foot structure that has withstood earthquakes, invasions, and time itself? Theories have ranged from brilliant ingenuity to wild speculation, but a discovery in 2013 may have finally pulled back the curtain on at least part of the mystery.

Hidden beneath the sands of Egypt’s Red Sea coast, archaeologists unearthed a set of papyri—the oldest known to humanity. Among them was the diary of Merer, an overseer tasked with transporting massive limestone blocks to Giza over 4,500 years ago. His records offer something few historical documents can: a firsthand glimpse into the daily lives of the workers who helped construct one of the most iconic structures in human history.

Yet, while Merer’s journal reveals the logistical prowess of the ancient Egyptians, it also underscores how much we still don’t know. His account details the movement of stone, but not how these blocks were lifted, positioned, or arranged with such mathematical precision. Instead of answering every question, this ancient scroll raises new ones, reminding us that the Great Pyramid remains one of history’s greatest unsolved puzzles.

The Discovery of the Red Sea Scrolls

In 2013, a team of archaeologists excavating Wadi al-Jarf, an ancient harbor along the Red Sea, uncovered a treasure trove of papyri—the oldest known written documents ever found. This remote site, once an active port during the reign of Pharaoh Khufu, served as a logistical hub for major construction projects across Egypt. Among the fragile scrolls was something extraordinary: the personal logbook of an official named Merer, a mid-ranking overseer responsible for moving massive limestone blocks from the quarries at Tura to the construction site of the Great Pyramid.

The discovery was groundbreaking. For the first time, scholars had direct evidence linking specific individuals, locations, and materials to the construction process. The scrolls detailed the organization of labor teams, the use of Nile river transport, and even the daily rations provided to workers. This was not speculation or secondhand accounts carved into temple walls centuries later—this was history written in real-time by someone who lived it.

Yet, despite the excitement surrounding this find, the contents of Merer’s diary offered only a partial answer to the mystery of how the pyramids were built. His records meticulously describe the movement of limestone for the pyramid’s outer casing, but they remain silent on the techniques used to construct its towering inner core. The true engineering marvel of Giza—the precision-cut blocks weighing several tons, the hidden chambers, and the near-flawless alignments—remains as puzzling as ever.

Merer’s Diary: A Firsthand Account of Pyramid Construction Logistics

For centuries, theories about how the Great Pyramid was built have sparked debates, ranging from ingenious engineering solutions to more far-fetched ideas. But Merer’s diary, written in real-time over 4,500 years ago, offers the most direct evidence of how materials were transported to Giza—a rare glimpse into the daily operations of pyramid builders.

As an inspector leading a team of approximately 200 men, Merer documented the movement of massive limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to the pyramid site. His records describe a highly organized operation: teams loaded the limestone onto boats, ferried it down the Nile, and then navigated through a network of canals leading to Giza. This process was crucial for completing the outer casing of the pyramid, the smooth white limestone layer that once gleamed under the Egyptian sun.

Beyond logistics, the diary also sheds light on the workforce itself. Far from the long-held notion of slaves toiling under brutal conditions, Merer’s men were well-fed and provided with rations of bread, meat, beer, and dates—suggesting they were skilled laborers, possibly part of a specialized construction workforce. The scrolls also mention a high-ranking figure: Ankhhaf, Khufu’s half-brother and the pyramid’s chief architect. This direct reference provides one of the strongest pieces of evidence linking an individual to the pyramid’s construction, adding a personal dimension to an otherwise anonymous historical event.

However, it’s important to recognize the limits of Merer’s diary. While it offers an unprecedented look at how limestone was transported, it does not explain how the pyramid itself was built. The intricacies of lifting, positioning, and aligning the massive stones that make up its core remain a mystery. This gap in knowledge underscores just how advanced Egyptian engineering truly was—and how much we still have to uncover.

What the Scrolls Confirm—and What They Don’t

For decades, historians and archaeologists have sought definitive answers about how the Great Pyramid was built. With Merer’s diary, we now have the earliest known firsthand account of pyramid-related labor, confirming key details about material transport. However, as significant as this discovery is, it also highlights the many gaps that remain in our understanding.

The papyri provide conclusive evidence that the smooth, white limestone casing stones were transported from Tura to Giza via an intricate waterway system. This insight reinforces the idea that the Egyptians had a sophisticated logistics network, capable of moving enormous quantities of materials with remarkable efficiency. Additionally, the mention of Ankhhaf—Khufu’s half-brother—strongly suggests that high-ranking officials oversaw the construction efforts, adding a layer of administrative control to the project.

But despite these valuable insights, the scrolls remain silent on the actual building techniques used to erect the pyramid’s core structure. The placement of the massive granite blocks in the King’s Chamber, the precision of the internal passageways, and the methods used to lift multi-ton stones to incredible heights remain unknown. How did the ancient Egyptians achieve such feats without modern machinery? Did they use ramps, pulleys, or some yet-to-be-discovered technique?

Merer’s diary answers an essential question—how the limestone for the pyramid’s outer casing was transported—but it does not unravel the deeper mysteries of the pyramid’s construction. Instead, it serves as a crucial but incomplete piece of a much larger puzzle.

Wadi al-Jarf: The Lifeline of Pyramid Construction

Merer’s diary not only sheds light on the transportation of limestone but also underscores the importance of Wadi al-Jarf—a long-forgotten Red Sea port that played a crucial role in pyramid construction. Located over 100 miles from Giza, this ancient harbor served as a vital logistical hub, linking Egypt’s interior with far-reaching trade and resource networks.

Archaeologists believe that Wadi al-Jarf was instrumental in supplying copper tools and other essential materials needed for pyramid building. Copper chisels and saws, though primitive by today’s standards, were critical for cutting limestone and shaping stone blocks. Since Egypt lacked significant copper deposits, shipments from the Sinai Peninsula and other regions were funneled through ports like Wadi al-Jarf before being transported along the Nile to the pyramid site.

This discovery reshapes our understanding of the infrastructure behind pyramid construction. It suggests that the project was not an isolated feat accomplished solely at Giza but rather a nationwide effort that relied on an extensive and well-coordinated supply chain. The fact that such an advanced logistical network existed over 4,500 years ago speaks to the sophistication of the Egyptian state.

Yet, even with this newfound knowledge, major questions remain. The existence of a structured workforce, supply routes, and administrative oversight confirms that pyramid building was a carefully planned operation—but it still does not reveal how the massive stone blocks were lifted and positioned with such precision. While Wadi al-Jarf helps us understand how materials reached Giza, the final stages of construction remain one of history’s greatest engineering puzzles.

News in the same category

Three holy water rituals many people practice at home before Christmas

If A Woman Says These 6 Things Regularly, She’s Way Smarter Than You Even Realize

11 Clever Phrases Smart People Use to End Pointless Arguments

8 Quiet Things People With Low Empathy Often Say Without Realizing It

Brutally Honest Reasons Older Women Say They Are Done With Dating

How to Travel Thousands of Miles Without Motion Sickness

China Unveils Its First Small Nuclear Reactor to Power 500,000 Homes and Cut Carbon Emissions

Physicists Discover Two New Types of Quantum Time Crystals

A 30-Year-Old Man Admitted to Hospital and Discovered to Have Acute Kidney Failure: It Was All Due to One Mistake in His Workout

Trick To Stop Mosquito Bite From Itching

A Family of Four Diagnosed With Liver Cancer: Experts Identified the Cause the Moment They Entered the Kitchen

Should We Eat Eggs With BL00D Spots

Scientists Crack an “Impossible” Cancer Target With a Promising New Drug

If You Love Being Alone, You Probably Have These 10 Qualities Others Envy

People Who Were Raised By Strict Parents Often Develop These 10 Quiet Habits

Six Money-Saving Habits That Can Quietly Increase Cancer Risk

Pouring Hot Water on Apples: A Simple Way to Detect Preservatives

9 Strange Feelings You’ll Experience Around People Who Aren’t Good for You

Scientists Discover Bats in the US Can Glow A Ghostly Green — and No One Knows Why

News Post

Three Ideal Times to Eat Boiled Eggs for Effective Weight Loss and Stable Blood Sugar

A 58-Year-Old Man Ate One Clove of Garlic Every Morning — His Medical Checkup Six Months Later Surprised Doctors

Yes, yes yes! This is what I've been looking for!

Periodontal Treatment as a Strategy for Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Protection

Frequency-Specific Electromagnetic Fields and Cancer Cell Behavior: Evidence and Limitations

Saffron as a Potential Antidepressant: Evidence from Clinical Trials

Metabolic Effects and Limitations of an Extreme Single-Food Diet: Insights from a Sardine-Based Experiment

The Therapeutic Role of Glutamine in Post-Infectious Irritable Bowel Syndrome

The Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Yogurt in Human Health

Mixing white salt with fabric softener solves many household problems and saves money

Misconceptions that turn water purifiers into breeding grounds for germs – stop using them immediately or you could harm your whole family

Secrets to longevity after age 50: The 'golden' drink for lasting health.

The phone has a special button that helps detect hidden cameras in motels and hotels, a fact many people are unaware of

Chinese actress triumphs over stomach cancer for 25 years: Her secret is doing 3 things every day.

Rice water: A wonderful "treasure," don't throw it away! How to use it for effective and cost-saving health care.

When a married woman is attracted to another man, she does these 9 things

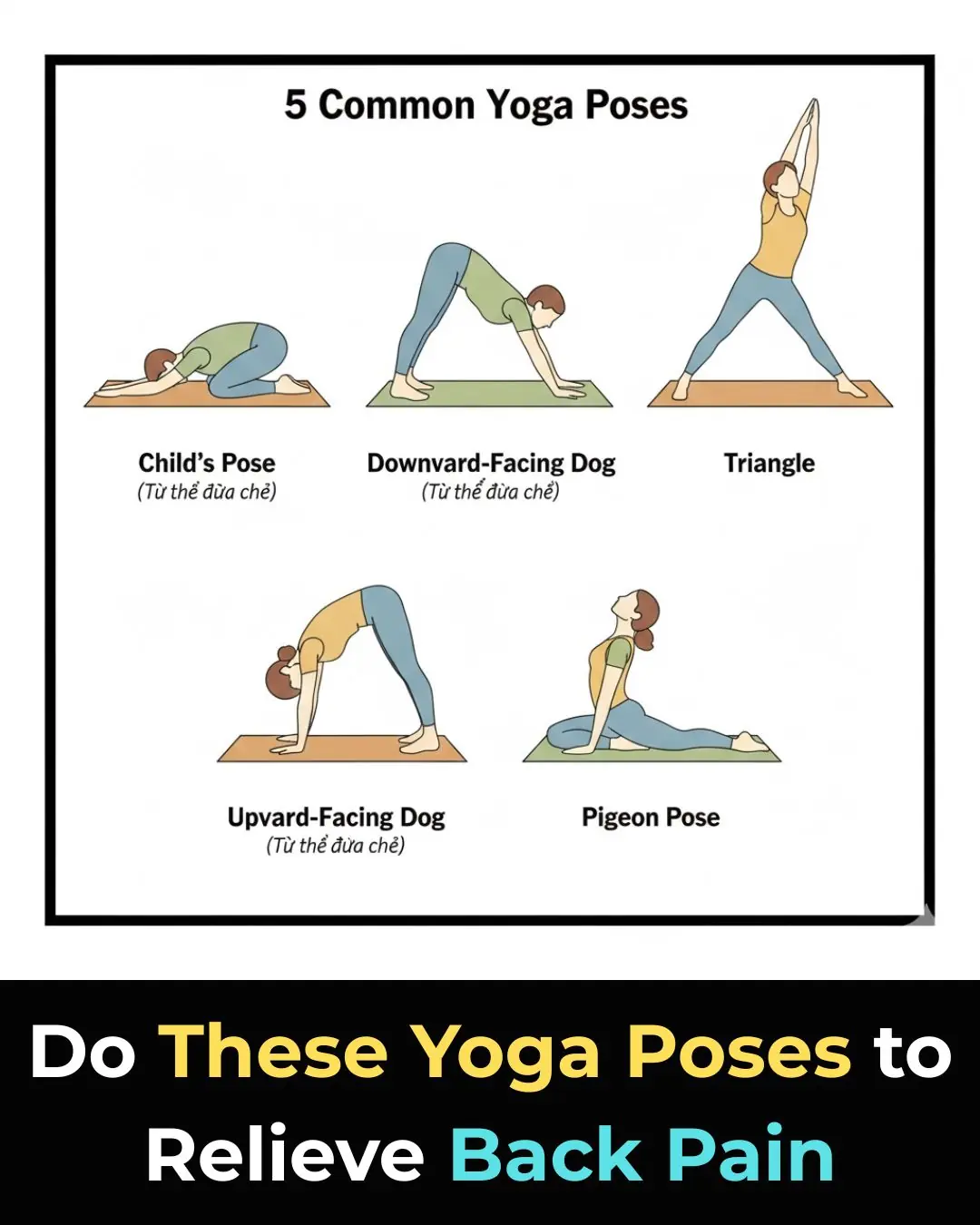

7 Yoga Poses That Can Help Relieve Lower Back Pain

Three holy water rituals many people practice at home before Christmas

Even old, non-stick pans can be "revived" with just a few simple tips that everyone should know