Why We Want to Exercise, Why We Don’t, and How to Start

President-elect John F. Kennedy published those words in Sports Illustrated in December 1960. But he could’ve been referring to American society in 2025.

Are we a generation — a society — of spectators?

We watch fit people more than ever. Three-quarters of the 100 most-watched primetime shows in 2024 were sportscasts. On the all-time list, 19 of the top 20 are Super Bowls.

Watching sports isn’t a new phenomenon. But watching fitness is.

On social media, fitness celebrities are so omnipresent that we’ve had to torture our language to describe them (“fitfluencers”) and what they do (“fitspo,” or “fitspiration” if you’re not into that whole brevity thing).

We see people exercise online and IRL. We see it in movies, on TV, and in commercials.

And here’s a telling stat: In the U.S., we have more gyms (55,294) than grocery stores (45,575).

And yet, according to the CDC, just 24% of us get the recommended amount of exercise and 25% don’t get any leisure-time physical activity at all.

And at a certain point, all this widespread societal trending and statistical ooing and aahing and tsk-tsking funnels down to the life and experience of just one person: You.

Are you a life spectator? Or a participant in the vigorous life, as Kennedy put it?

Let’s try a little experiment. Read the next few sections and see how much you see yourself in the information. It could be very illuminating.

Doing More, but Also Doing Less

Our society seems to be in the throes of an I-want-to-but-just-can’t-right-now conundrum when it comes to being physically active.

In 2018, 54% of us met the minimum guideline for aerobic exercise (at least 150 minutes a week of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity), which is up from 43% in 2008. And 28% met the twice-a-week guideline for resistance exercise, up from 22%. That’s good!

“Our data shows that more Americans than ever before are actively engaged in fitness,” said Anton Severin, vice president of research for the Health & Fitness Association.

Gym membership, according to the HFA, is at an all-time high. About 73 million Americans belonged to a health club in 2023. They visited the facility about 1.5 times a week, on average.

And then, like a New Year’s resolution trying to survive to see March, a falloff:

Severin noted disparities in the numbers: About 30% of gym members swipe their cards less than once a month, while 11.5% are “highly engaged users,” which means they show up four or more times a week.

The trends for both groups are significantly different from the pre-pandemic years. The percentage of low-frequency members has doubled since 2019, Severin said, while the gym-rat cohort has fallen more than 40%.

Those good-news, bad-news numbers are emblematic of Americans’ love-hate relationship with exercise. It’s been that way for a long, long time.

How Fitness Went Mainstream

“Looking fit, being fit, and the act of partaking in fitness is all very aspirational,” said Danielle Friedman, a journalist and author of Let’s Get Physical: How Women Discovered Exercise and Reshaped the World. “We assign and project all sorts of positive attributes onto all of those things.”

As Friedman explained in a New York Times article earlier this year, the links between aspiration and perspiration were forged in the 1960s.

Back then, the health club business was in its infancy. Vic Tanny’s facilities, for example, tried to attract a new clientele with “carpeted floors, mirrored walls, and pastel colors.” Resistance exercise was made less intimidating with chrome weights and “futuristic machinery.”

The running boom took sweat off the carpets and into the streets. It was followed in the 1970s by the aerobics revolution, which brought it back indoors.

By the 1980s, with the increasing popularity of strength training, all the trends converged to give us fitness facilities as we know them today: treadmills for running; studios for aerobics, yoga, and other group classes; and acres of floor space for lifting, stretching, or, increasingly, looking at your phone while people around you lift, stretch, and look at their phones.

One thing that unites the most and least engaged people in the gym: what they wear.

Dressing the Part

Fitness trends often inspire corresponding fashion trends. Non-runners started wearing running shoes. Jazzercise and Jane Fonda made leotards and leg warmers a common sight, setting the stage for the ubiquity of athleisure and yoga pants today.

“Looking sporty became chic,” Friedman said. “It also came to signal that you were somebody who valued working out and maybe had the work ethic. By wearing the costume, you could project, to an extent, a lot of the positive associations with exercise.”

The fashion trends helped motivate people to take up the exercise that inspired them. That was especially prevalent with dancewear. “Leotards and spandex weren’t particularly forgiving,” Friedman said. For many women, it took a lot of work to look like someone who should be wearing those things (and conversely, men trying to convincingly rock a tank top).

New clothing can get someone into the gym. But can it keep them coming back? The challenge, then as now, is converting that initial motivation to exercise into a lifelong habit.

Why Watching Doesn’t Lead to Doing

According to Kathleen Martin Ginis, PhD, co-author of The Psychology of Exercise, we consume fitness-related content for three primary reasons:

First, she said, “there’s the aesthetic of it. People like to look at fit, healthy bodies.”

Then there’s the sense of awe we feel when extraordinary people do extraordinary things.

Finally, there’s the emotional catharsis we get from seeing someone’s accomplishment or transformation.

One thing we probably won’t get? The urge to exercise.

That’s especially true of “thinspiration” content on social media. “While people might think it’s motivating, we know it’s actually not,” she said. “It just makes people feel worse about themselves.”

Martin Ginis, director of the Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Management at the University of British Columbia, sees exercise behavior as falling into three general categories:

- Nonintenders don’t want to exercise.

- Intenders want to exercise but don’t.

- Actors have a fitness routine they follow more or less consistently.

“To move intenders to actors, it’s not easy, but at least they’ve got the motivation,” she said. What they haven’t yet figured out is a way to get over, around, or through their obstacles.

A common barrier, she said, is someone’s “gut reaction to thinking about exercise.”

And that’s way more complex than we can see from the outside.

From Gawking to Grinding

Admiring individuals with great physiques is hardly new. It predates social media by more than 100 years.

Audiences lined up to gawk at bodybuilder Eugen Sandow in the 1890s. The acrobats and strength athletes at Muscle Beach in Santa Monica drew crowds for three decades and provided a launching pad for fitness pioneer Jack LaLanne and action movie star Steve Reeves, among many others.

The idea that the less gifted among us should emulate these physical and athletic outliers is relatively new. But it’s loaded with baggage from the past.

“We’re conditioned to have a really narrow understanding of what fitness looks like,” Friedman said. Our perceptions are so skewed that even elite athletes like NFL quarterback Patrick Mahomes and NBA point guard Luka Doncic get mocked because they don’t look like underwear models.

“If you’re going to be in a public fitness space, you have to look like you know what you’re doing and look like you belong,” Friedman added. “If you don’t fit that mold, it creates an extra layer of challenges and barriers that require some fortitude to push through.”

Which makes sense. Who wants to be the “before” picture in a room full of “afters?”

So instead of focusing on how many people don’t exercise, maybe we should ask why so many do. And how about you?

When Movement Becomes Meaningful

What separates lifelong exercisers from everyone else? Martin Ginis’ research offers an answer.

“If you look at people’s emotional response to exercise, it’s the extent to which they’re having good-quality exercise experiences,” she said.

A positive exercise experience offers at least one of six things:

- Autonomy

- Belonging

- Challenge

- Engagement

- Mastery

- Meaning

Which one of the six keeps someone going is entirely individual.

“I may need to experience belonging, you may need to experience mastery,” Martin Ginis explained. “And those values, needs, and preferences likely vary over time and in different contexts.”

Notice what’s not on the list? Minutes. Step counts. Frequency. Target heart rate.

All those things might contribute to the challenge of exercise or someone’s sense of autonomy or mastery. But as standalone variables, they aren’t motivating — even though official guidelines focus on them almost exclusively.

Something else that isn’t on the list: what you see on the scale or in the mirror.

“We know exercising for appearance-related reasons — wanting to lose weight, fitting a certain body ideal — is the least motivating and least effective in helping people stick with a movement habit long-term,” Friedman said.

To be clear, appearance-related goals are a nearly universal starting point, “the No. 1 reason people start exercising,” according to Martin Ginis. But research shows it’s rarely sustainable for more than a few weeks or months (hence the annual deaths of millions of New Year’s resolutions).

Those who keep going, Martin Ginis said, “start finding other reasons to exercise.”

See if any of these sound familiar or good to you:

- The structure of an exercise routine helps you get more done at work or home.

- You notice improved energy or focus — it makes you feel alive.

- You feel healthier and your numbers at the doctor’s office improve.

- You feel invigorated by sweating with a group of like-minded individuals in a running club or group class.

- You realize everyday movements and tasks like carrying things and taking the stairs are suddenly — gloriously — easier.

“That’s when the shift happens,” she said.

A positive emotional connection to physical activity.

It doesn’t happen for everyone, obviously. But when it does, you realize how much better it is to be in the game instead of watching it from the sidelines.

News in the same category

Why Your Blood Pressure Is Higher in the Morning

This 20-Minute Treadmill Workout Builds Strength After 50

The Best Times to Eat Yogurt for Effective Weight Loss and Gut Health

"The King of Herbs": Aids Heart Health and Helps Dissolve Kidney Stones

Menstrual Blood–Derived Stem Cells and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence from Preclinical Research

Household Chores and the Development of Executive Functions in Children

Edible Mushroom Consumption and the Prevention of Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction

Anticancer Potential of Mastic Gum Resin from Pistacia atlantica: Evidence from In Vitro Colon Cancer Models

The Effects of Raw Carrot Consumption on Blood Lipids and Intestinal Function

Off-the-Shelf CAR-NKT Cell Therapy Targeting Mesothelin: A New Strategy Against Pancreatic Cancer

The Truth About the Link Between Sugar and Cancer

Beware! 7 Neuropathy Causing Medications You Need to Know

Doctors have summarized five warning signs that a person's body typically gives in the year before death

Woman lost both kidneys before turning 30: Doctor warns of 2 habits that cause kidney failure

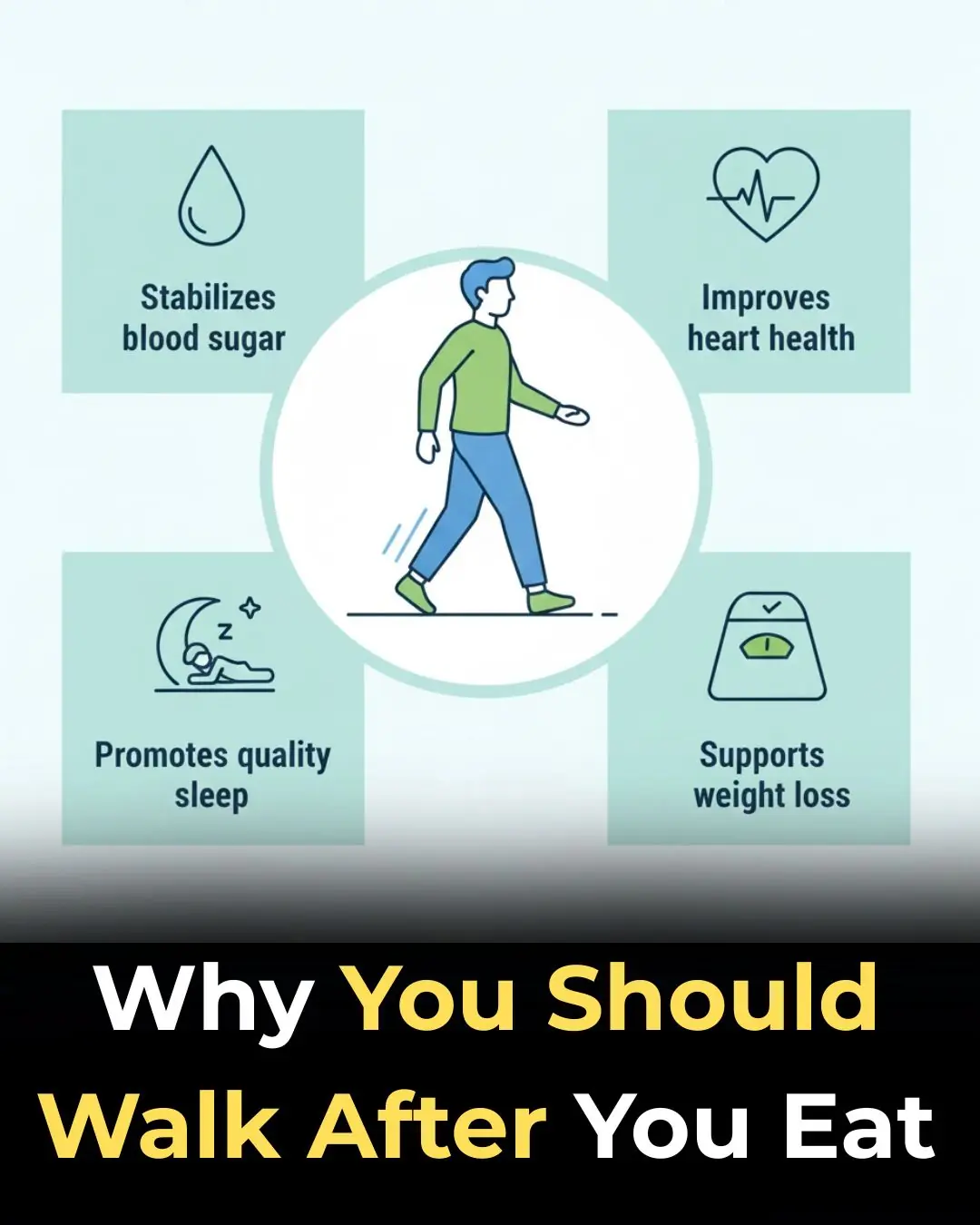

Why Walking After Eating Is So Good for You

The Best Scientifically Proven Foods to Cleanse Your Liver

5 Common Habits That Quietly Damage Your Knees

Why Hot Dogs and Processed Meat Might Be the Most Dangerous Foods of All Time

Epstein–Barr Virus May Reprogram B Cells and Drive Autoimmunity in Lupus

News Post

HealthWhy Your Hard-Boiled Eggs Have That Weird Green Ring

Why Your Blood Pressure Is Higher in the Morning

This 20-Minute Treadmill Workout Builds Strength After 50

The Best Times to Eat Yogurt for Effective Weight Loss and Gut Health

"The King of Herbs": Aids Heart Health and Helps Dissolve Kidney Stones

Menstrual Blood–Derived Stem Cells and Amyloid Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease: Evidence from Preclinical Research

Household Chores and the Development of Executive Functions in Children

Edible Mushroom Consumption and the Prevention of Subclinical Thyroid Dysfunction

Anticancer Potential of Mastic Gum Resin from Pistacia atlantica: Evidence from In Vitro Colon Cancer Models

The Effects of Raw Carrot Consumption on Blood Lipids and Intestinal Function

Off-the-Shelf CAR-NKT Cell Therapy Targeting Mesothelin: A New Strategy Against Pancreatic Cancer

The Truth About the Link Between Sugar and Cancer

Most people will go their entire life without ever knowing what the drawer under the oven was actually designed for

Beware! 7 Neuropathy Causing Medications You Need to Know

Doctors have summarized five warning signs that a person's body typically gives in the year before death

Why do many people recommend squeezing lemon juice into the oil before frying?

Woman lost both kidneys before turning 30: Doctor warns of 2 habits that cause kidney failure

10 Things Women Who Have Been Heartbroken Too Many Times Do

Best Vitamins & Foods for Hair Growth