A Massive Spider Megacolony Thriving in a Sulfur-Fueled Cave Ecosystem

A Vast Spider Metropolis Hidden Beneath Europe

Deep within a sulfur-rich cave straddling the remote border between Albania and Greece, scientists have uncovered one of the most extraordinary arachnid communities ever documented. Hidden far from daylight, an immense, interconnected web system stretches across roughly 1,140 square feet and is inhabited by an estimated 111,000 spiders. What makes this discovery especially remarkable is not only its sheer scale, but also the unexpected coexistence of two spider species that would rarely tolerate one another under normal circumstances.

The colony is composed primarily of Tegenaria domestica, a species commonly known as the house spider, and Prinerigone vagans, a much smaller sheet-weaving spider. In surface environments, these species typically compete for space and prey. Yet inside the pitch-black cave, where sunlight never penetrates and conditions are chemically extreme, competition appears to have been replaced by a form of coexistence that borders on cooperation. Researchers believe that the absence of light and predators, combined with limited but stable food resources, has reshaped the spiders’ behavior, allowing them to build overlapping webs and tolerate close proximity.

Unlike most ecosystems on Earth, this underground environment is not driven by photosynthesis. Instead, it is sustained by sulfur-oxidizing bacteria that draw energy from chemical reactions involving sulfur compounds present in an underground stream. These bacteria form dense microbial mats, which in turn provide food for non-biting midges. The spiders occupy the top of this unusual food chain, feeding almost exclusively on these insects. Similar sulfur-based ecosystems have been documented in places such as Movile Cave in Romania, one of the world’s best-known chemosynthetic cave systems (National Geographic; Nature Ecology & Evolution).

Genetic and DNA analyses have revealed another layer of adaptation. The cave-dwelling spiders possess a gut microbiome that is distinctly different from that of their surface-dwelling relatives. Scientists suggest that this specialized microbiome helps the spiders digest prey that ultimately depends on sulfur bacteria, demonstrating how even familiar species can undergo subtle but important biological changes when exposed to extreme environments. Such findings align with broader research showing that microbiomes play a crucial role in helping animals adapt to harsh or unusual diets (Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

Beyond its biological novelty, the discovery challenges long-held assumptions about spider behavior. Spiders are typically considered solitary and territorial, yet this massive web network functions almost like a shared infrastructure, enabling thousands of individuals to coexist in close quarters. While the spiders are not truly social in the way ants or bees are, the structure of the colony suggests that environmental pressure can push even solitary species toward unexpected social-like arrangements (BBC Earth; Scientific American).

Researchers emphasize that this cave ecosystem deserves special protection. Its size, the rare interaction between species, and its reliance on sulfur-based energy make it virtually unique in Europe. Human disturbance, pollution, or changes in groundwater chemistry could easily disrupt the delicate balance that sustains the entire system. More broadly, the discovery highlights how little is still known about subterranean ecosystems and how many surprises remain hidden beneath our feet.

Ultimately, this underground spider metropolis serves as a powerful reminder that life is remarkably adaptable. Even creatures as familiar as house spiders can evolve new behaviors and biological traits when pushed into extreme and isolated environments, reshaping our understanding of where and how complex life can thrive.

News in the same category

Burglar Uncovers Shocking Crime During Robbery, Turns Himself In and Exposes Serious Offense

The Black Diamond Apple: A Rare Gem from the Mountains of Tibet

Marvin Harvin Becomes One of the First Incarcerated Individuals to Graduate from Yale University, Highlighting the Power of Education in Prison Reform

Warren Buffett’s Ice Cream Quote: A Simple Yet Powerful Lesson on Taxes

Why Do Button-Down Shirts Have Loops On the Back

World's Oldest Little Blue Penguin Reaches Remarkable 25 Years in Managed Care

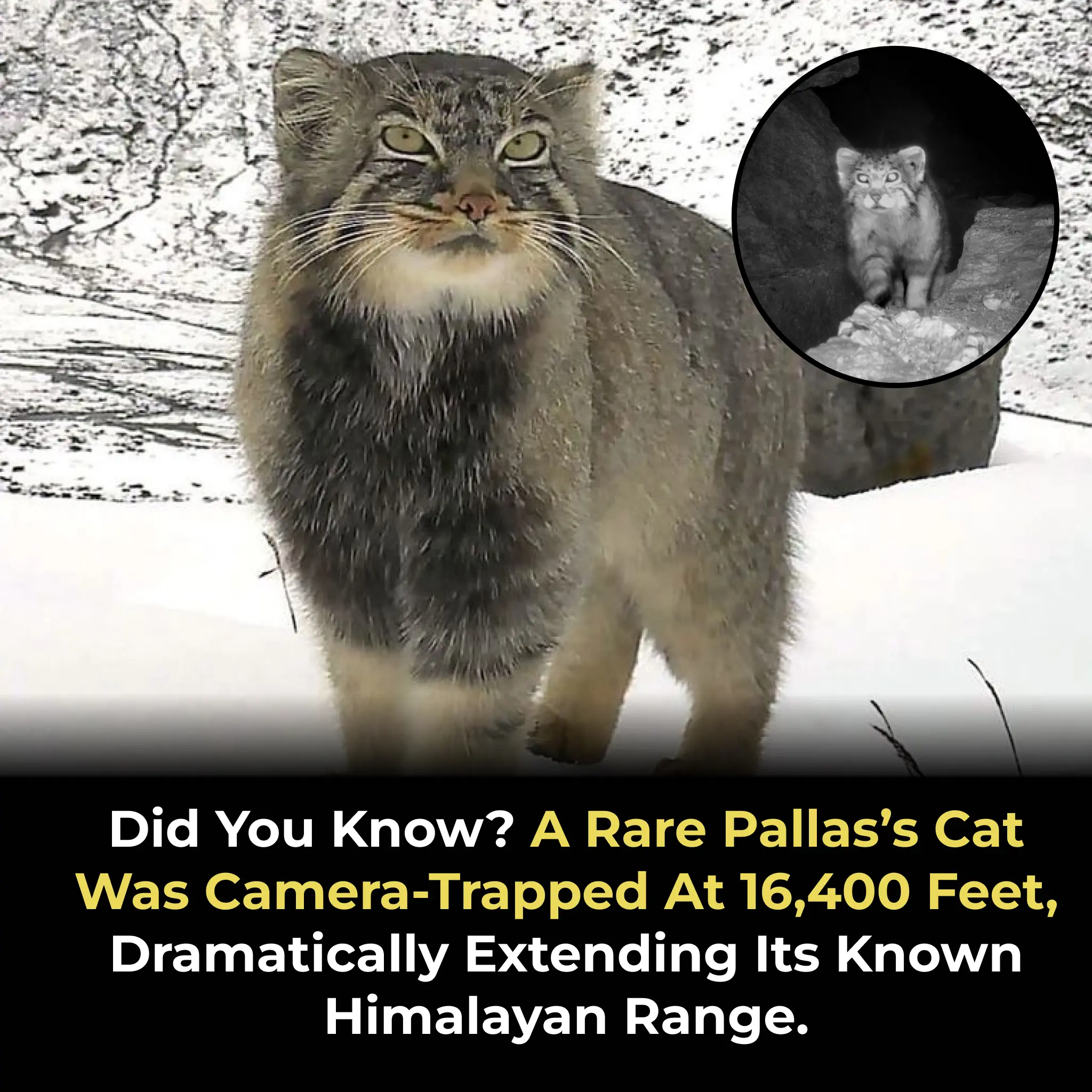

Rare Sighting of Pallas's Cat at 16,400 Feet in the Himalayas Reveals Remarkable Adaptability

Studies Suggest Links Between Swearing, Staying Up Late, and Higher Intelligence

Kenya Records Historic Elephant Baby Boom in National Park: 140 Calves Born in One Year

Photograper Captures A Once-In-A-Lifetime Shot Of A ‘Horizontal Rainbow’ That Filled The Whole Sky

Afghan Men Detained for Dressing Like "Peaky Blinders" Characters, Authorities Claim Promotion of Foreign Culture

Austrian Man Arrested for Manslaughter After Leaving Girlfriend to Freeze on Grossglockner Peak

Midea Group Unveils MIRO U: A Revolutionary Six-Armed Super Humanoid Robot for Factory Automation

A Touch of Viking Brilliance: Moss-Carpeted Homes in Norway

China Conducts World’s First Wireless Train Convoy Trial, Moving Nearly 40,000 Tons of Cargo

Gene-Edited Immune Cells Reverse Aggressive Blood Cancers in World-First Human Trial

Dutch Artist Berndnaut Smilde Creates Fleeting Indoor Clouds to Explore Transience and Atmosphere

Starlings Obscure the Sky Over Rome: A Dystopian Viral Photo

News Post

Rapid Pain and Stiffness Relief in Knee Osteoarthritis

Tamarind: The Tangy Superfruit Your Body Will Thank You For

Why Your Legs Show Signs of Aging First — and 3 Drinks That Can Help Keep Them Strong

Intensive Gum Disease Treatment Slows Artery Thickening, Benefiting Heart and Brain Health

The #1 Food Proven to Support Kidney Cleansing and Protection

High Olive Oil Intake Linked to Significantly Lower Risk of HER2-Negative Breast Cancer

Tight Junction Proteins and Permeability Improved by Roasted Garlic in Mice with Induced Colitis

Randomized Controlled Trial Confirms NEM® Efficacy and Safety in Reducing Osteoarthritis Pain and Stiffness

Whole Fish Trumps Pills: Study Finds Whole-Food Factors, Not Isolated Omega-3s, Lower Autism Risk

Dark chocolate and tea found to significantly lower blood pressure

Burglar Uncovers Shocking Crime During Robbery, Turns Himself In and Exposes Serious Offense

The Black Diamond Apple: A Rare Gem from the Mountains of Tibet

The Power of Pine Needles: 30 Benefits and Homemade Uses

Marvin Harvin Becomes One of the First Incarcerated Individuals to Graduate from Yale University, Highlighting the Power of Education in Prison Reform

The Hidden Power of Pistachio Shells: Benefits and Clever Homemade Uses

Warren Buffett’s Ice Cream Quote: A Simple Yet Powerful Lesson on Taxes

Papaya Seeds: A Powerful Remedy for Liver Health and How to Use Them as a Pepper Substitute

30 Amazing Benefits of Lactuca serriola (Wild Lettuce)