Japan Unveils World’s First Artificial Womb, Enabling Embryos To Grow Outside The Human Body

Artificial Wombs: Japan’s Breakthrough and Humanity’s Next Frontier

When Japanese scientists revealed they had successfully nurtured mammalian embryos in a fully artificial womb, the announcement reverberated around the world. It wasn’t just the sheer brilliance of the achievement that drew attention—it was the future it pointed toward. For the first time, life had been initiated and sustained entirely outside a living body. This step goes far beyond incubators or neonatal intensive care. It enters a realm once confined to science fiction, where the uterus itself can be replaced by engineered systems.

This technology isn’t merely about helping premature babies survive; it is about beginning life in a laboratory without the involvement of a natural pregnancy. The questions it raises—ethical, social, political—are as staggering as the possibilities it creates. Could it reshape parenthood, address Japan’s population crisis, or redefine how humanity views reproduction? As we stand at the threshold of this transformation, society must grapple with both its promise and its peril.

The Scientific Breakthrough – Redefining the Beginning of Life

Researchers at Juntendo University in Tokyo achieved what many thought impossible: an artificial womb capable of sustaining mammalian embryos entirely outside the body from the earliest stage of development. Unlike incubators, which support infants already born, this device begins gestation itself.

The system consists of a transparent biobag filled with oxygenated artificial amniotic fluid. An external umbilical cord provides nutrients and removes waste, while advanced sensors track fetal heartbeat, growth, and even subtle movements. Artificial intelligence helps regulate conditions, making real-time adjustments to mimic the biological precision of a natural womb.

In their experiments, the team grew goat embryos for several weeks—long enough to demonstrate viability and establish proof of concept. Scientists call this ectogenesis, the full development of life outside the womb. Previous attempts—such as the 2017 Philadelphia experiment that supported premature lambs—offered partial gestation. Japan’s achievement pushes the boundary further back to the embryonic stage, crossing a threshold between supporting life and truly initiating it.

While full-scale human application remains years away, experts believe partial uses in neonatal medicine could arrive within a decade. Each incremental advance blurs the once-clear line between biological certainty and technological possibility.

Why Japan—And Why Now?

Japan’s leadership in this field is not accidental. The nation faces a profound demographic crisis. In 2024, births fell to their lowest recorded level, and nearly 30% of the population is over age 65. Despite government efforts—financial incentives, childcare subsidies, longer parental leave—the fertility rate shows no signs of recovery.

In this context, artificial wombs become more than a medical innovation; they emerge as a potential social lifeline. For Japanese women, pregnancy often collides with cultural expectations of long work hours and rigid career dedication. Many delay or avoid motherhood, citing the heavy personal and professional costs. By externalizing gestation, artificial wombs could ease these burdens, enabling women to pursue careers while still becoming parents.

The technology also suggests more inclusive family models. Same-sex couples, single individuals, and people unable to carry pregnancies could gain new pathways to parenthood. Japan, with its tradition of applying robotics and automation to societal challenges—from elder care to workforce shortages—may see ectogenesis as a natural extension of its pragmatic embrace of technology. What might appear radical elsewhere looks, in Japan, like a strategic response to existential demographic pressures.

The Ethical Crossroads

Yet every step forward comes with profound ethical dilemmas. When gestation is no longer bound to the human body, fundamental questions arise:

-

Who decides when to terminate or alter a pregnancy if no mother’s body is involved?

-

What legal status should an embryo have inside a machine?

-

Who is accountable if a technical failure endangers developing life—the parents, the engineers, or the state?

There are also concerns about commercialization. Could corporations patent artificial womb technology, creating a future where access is restricted to the wealthy? Would embryos be cultivated for research or profit, pushing human reproduction into a market-driven system? Without strong regulations, artificial wombs risk deepening inequality in reproductive health.

Security is another issue. A natural womb is private, but a machine can be hacked, manipulated, or sabotaged. The prospect of “cyber risks” to gestation raises new dimensions of vulnerability no previous generation has faced.

Beyond these practical worries lies something more intangible: the loss of intimacy. Pregnancy has long been seen as both a biological process and a deeply human experience—a rite of passage that shapes identity, family bonds, and emotional connection. While removing health risks is undeniably positive, some fear that outsourcing gestation could erode the meaning of motherhood, turning birth into a sterile transaction.

Ethical progress must keep pace with science. That means involving not just doctors and engineers, but ethicists, lawmakers, religious leaders, and the public. If artificial wombs redefine the origins of life, society must collectively decide what values will guide this transformation.

Redefining Parenthood and Family Structures

The potential ripple effects extend far beyond medicine. Artificial wombs challenge traditional notions of parenthood, gender roles, and family itself. For centuries, the ability to carry a child has shaped social dynamics, often placing disproportionate expectations on women. By relocating pregnancy into a lab, technology opens the door to a more equal distribution of parenthood—one that emphasizes intention and caregiving rather than biology.

This could normalize new forms of family: same-sex couples having biological children, older parents extending fertility, or individuals choosing parenthood outside of conventional partnerships. It could also eliminate reliance on surrogacy, which is often fraught with ethical and legal complications.

But this democratization of reproduction brings risks. If artificial wombs are marketed as safer or more efficient than natural pregnancy, women who choose to carry children could face stigma for rejecting a “modern” option. Society might stratify between “natural-born” and “synthetic-born” children, raising questions about identity and equality. Language itself may shift—what does it mean to be a “mother” when no body is involved?

Some scholars predict that family in the future will be defined less by biology and more by intention, consent, and technology. That vision could bring greater inclusivity, but only if society is willing to confront its complexities openly.

Standing at the Threshold

Japan’s artificial womb breakthrough marks the start of a new chapter in human history. The science is dazzling, the implications staggering, and the ethical questions unavoidable. Whether this innovation becomes a tool for empowerment or a source of division will depend not on machines, but on the choices we make as a global community.

The artificial womb is not just a device—it is a mirror, reflecting our hopes, fears, and values. It forces us to ask: if we can redesign the very origins of life, how should we? And more importantly, who gets to decide?

News in the same category

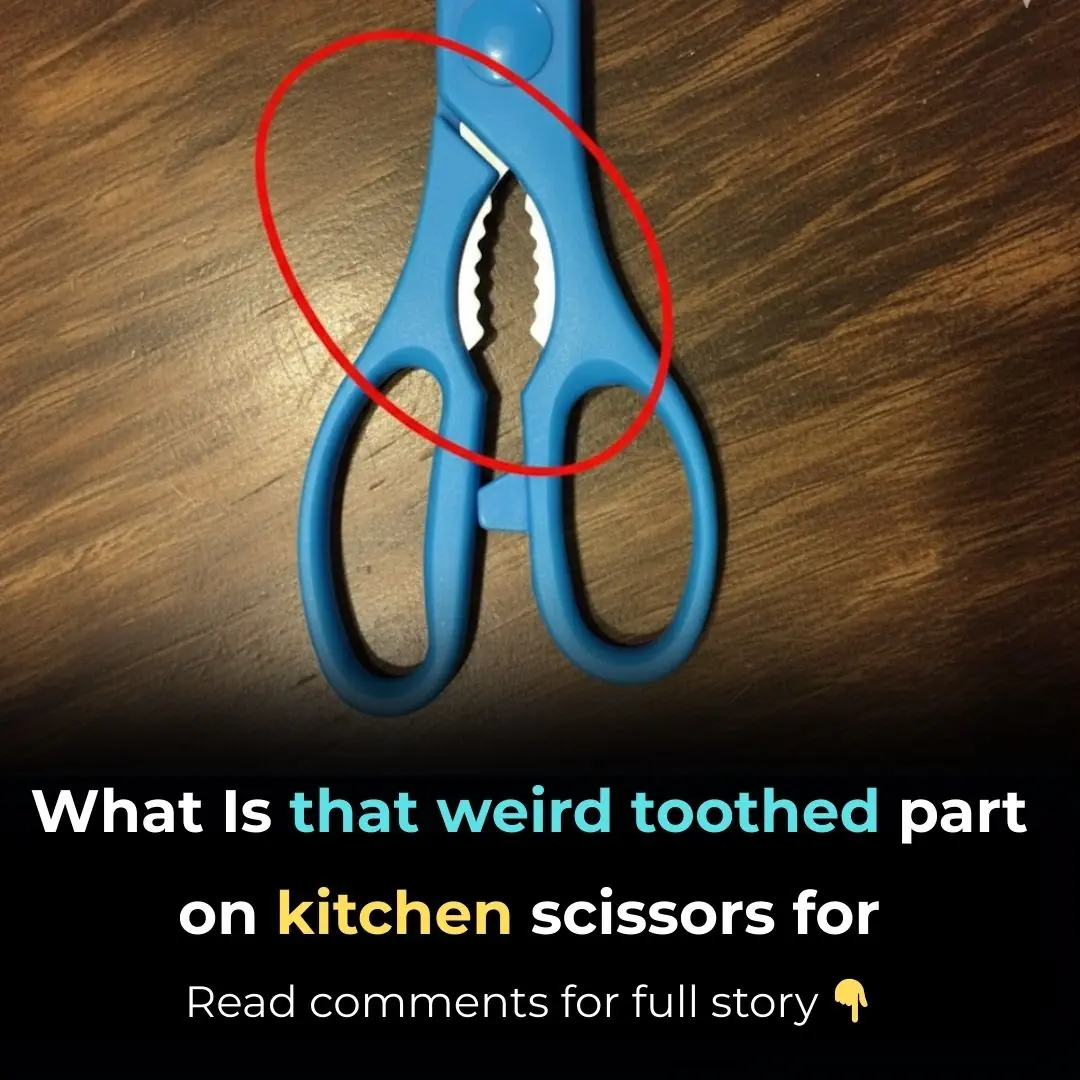

Weird Toothed Part on Kitchen Scissors

Ring Finger Longer Than An Index Finger

The Story Behind Two Runaway Graves in Savannah Airport

The Simple Object That Might Baffle the Younger Generation

Why Public Bathroom Doors Don’t Reach the Floor – The Real Reason Revealed

The gaps and inward-swinging doors are designed for practicality, serving purposes like enhancing safety and improving efficiency, rather than being the result of poor design.

World’s Oldest Woman Lived to 117 By Eating the Same Meal Every Day

Emma Martina Luigia Morano, the world’s oldest woman at the time of her passing, credited her extraordinary 117 years of life to a mix of genetics, resilience, and one very peculiar daily diet. Her remarkable story spans two World Wars, personal tragedy

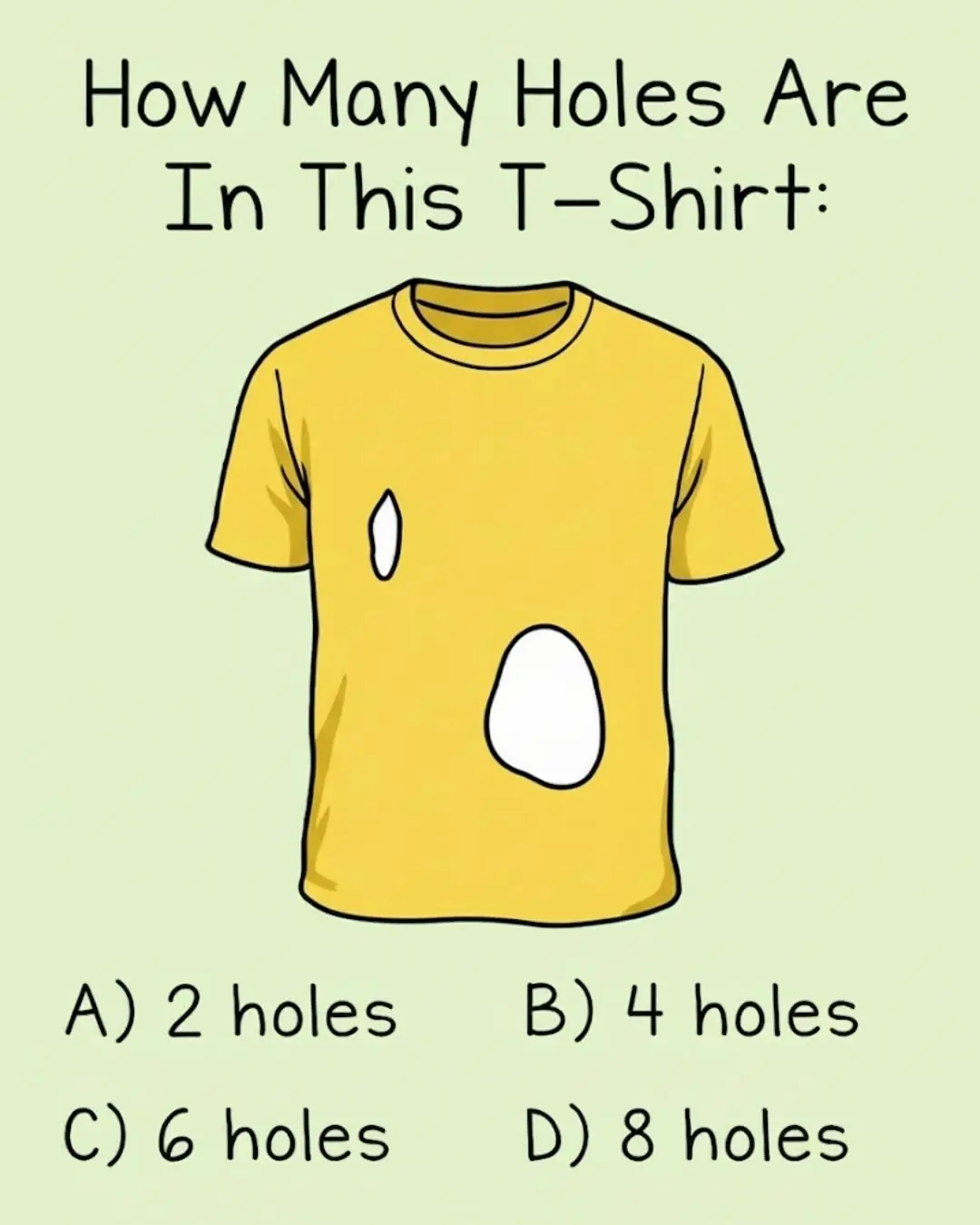

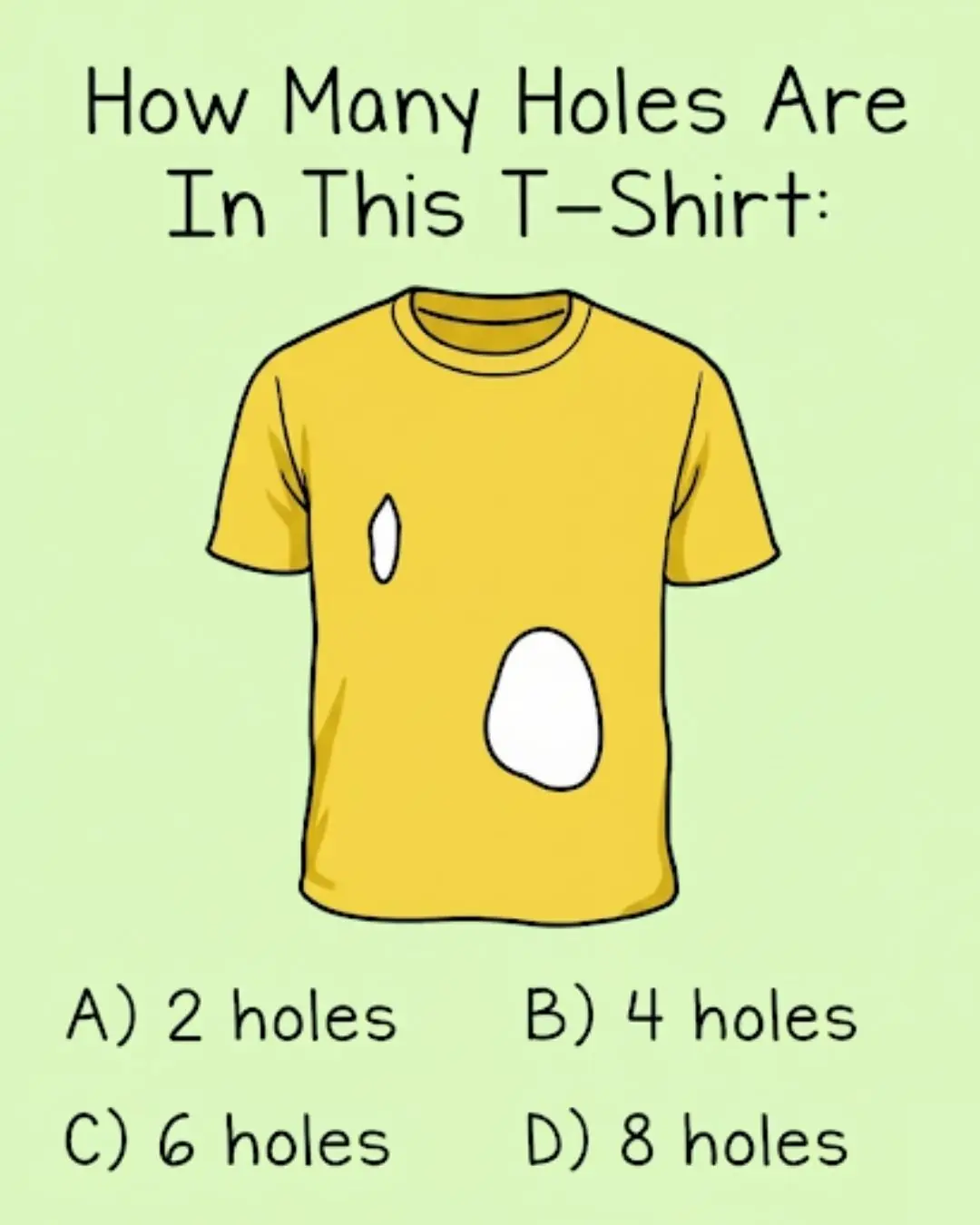

Simple T-Shirt Image Is Driving the Internet Crazy

Scientists Discover Dogs Dream About Playing With Their Owners

Rare 9/11 Footage Reveals Heartbreaking Close-Up of Second Plane Striking Tower

Here’s Why Many Couples Start Sleeping In Separate Beds After 50

Hotel Room Red Flags You Should Never Ignore

The Hidden Fish Puzzle That’s Stumping the Internet

What Are the Loops on the Back of Button-Down Shirts For?

‘Folded Boy’ Miraculously Stands Tall After Years Living With 180° Spine Bend

For over a decade, a young man in China lived with his body bent nearly in half, trapped in a painful “Z-shaped” posture that made everyday life a struggle. Now, after years of suffering and a series of groundbreaking surgeries, he has finally stood u

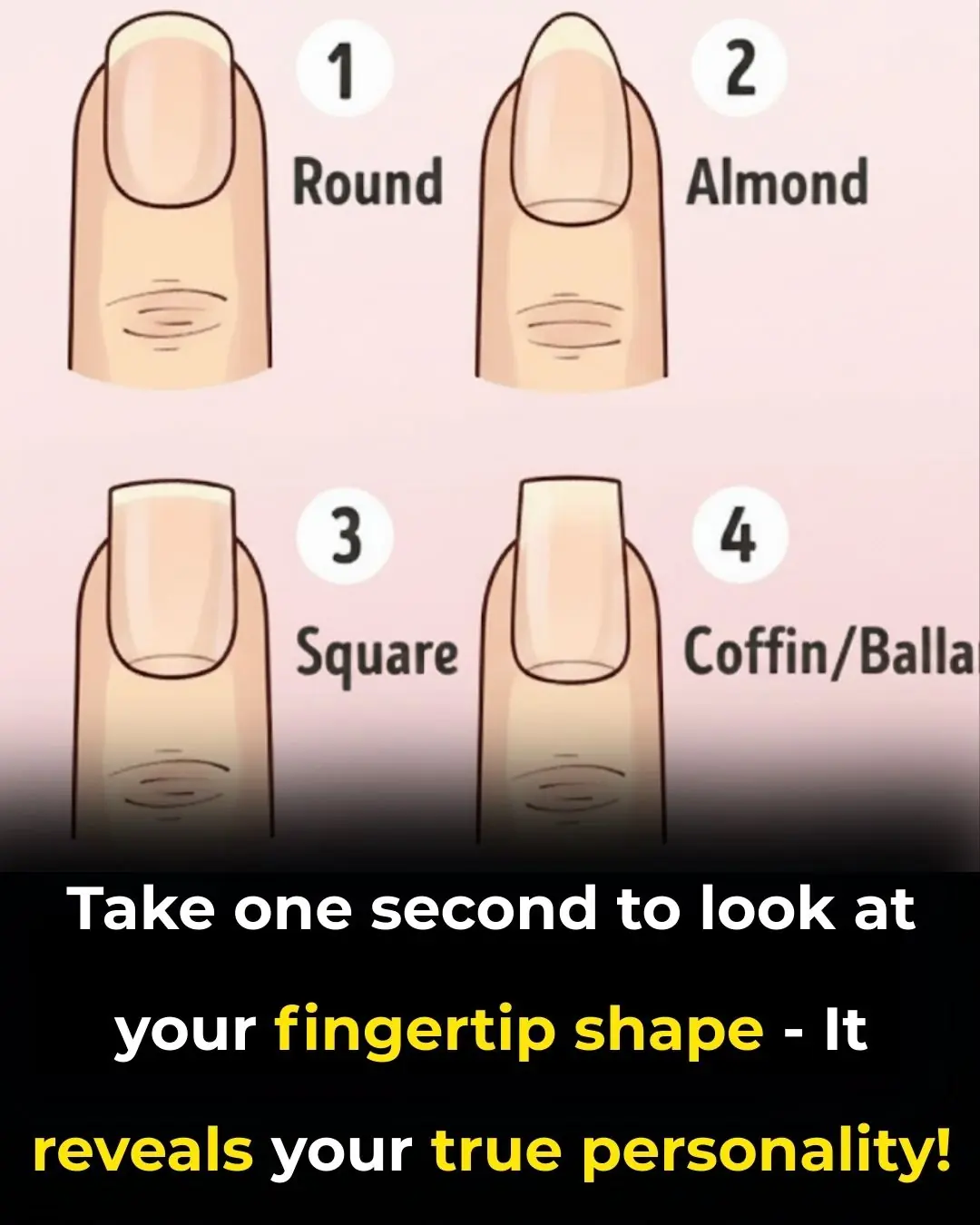

The shape of your fingertips reveal your true personality

Lonely In Old Age

Simple T-Shirt Image Is Driving the Internet Crazy

Couple’s Walk Leads to a Rare $70,000 Ambergris

News Post

Symptoms That Can Be Caused by Stress

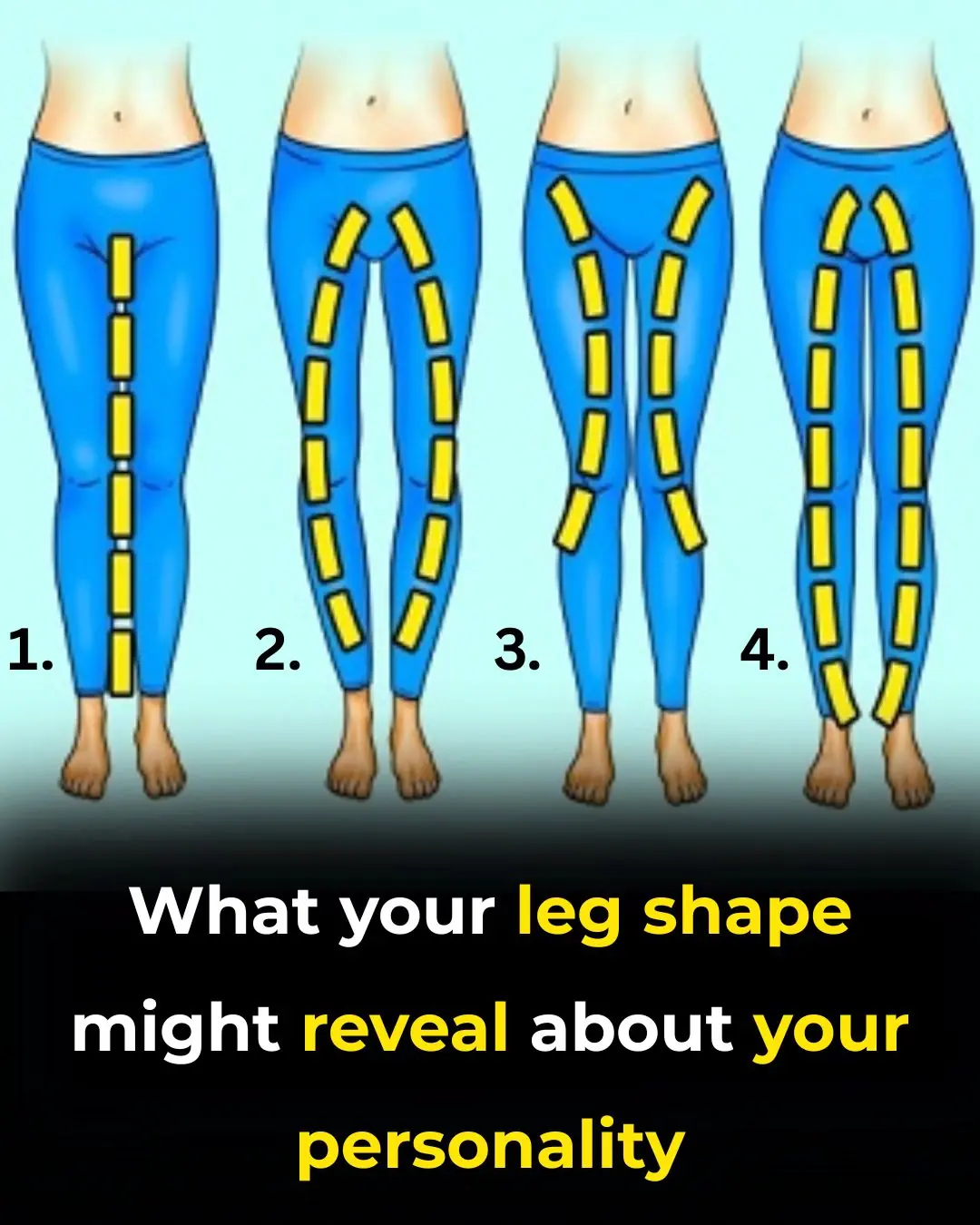

What the Shape of Your Legs Might Say About Your Personality

How surgeon who amputated his own legs was caught as he's sentenced to 32 months in prison

PlayStation handing out rare refunds to gamers over popular new game

🌿 17 Health Conditions That May Benefit from Guava Leaf Tea + Easy Homemade Recipe

If your non-stick pan has lost its coating, don't rush to throw it away: Just do this, and you can fry and cook without it sticking or falling apart.

The golden 4-hour window for drinking coffee helps your body gain maximum benefits: detoxifying the li:ver and promoting smooth digestion.

Eating boiled bananas at this time, after just 1 week, your body will experience 7 changes

Add potato to coffee to get rid of wrinkles in just 1 week

Homemade Rice water & Methi Dana Toner for Glowing Skin

The DIY anti-ageing cream that is very effective to get rid of wrinkles and fine lines on your face

Herbal Remedies for Strong, Lush Hair: Easy Recipe Everyone Can Make At Home

Flaxseed Gel for Wrinkles: The Natural DIY Solution for Smoother, Youthful Skin

10 Tomato Slice Skincare Remedies for Wrinkles, Pores, and Glowing Skin: Natural DIY Treatments

Super Effective DIYs to Achieve Soft, Pink, and Perfect Lips

A Scientific Look at Oregano’s Role in Supporting Wellness

Reverse Hair Greying Naturally: Effective Treatments and Remedies for Restoring Hair Color

The Incredible Benefits of Plantago lanceolata and How to Use It

CCF Detox Drink For Glowing Flawless Skin