Life and death have long been considered opposites, yet the discovery of new multicellular life emerging from the cells of a deceased organism challenges this traditional view. This phenomenon introduces an intriguing “third state”—a condition that exists beyond the conventional boundaries of life and death.

Typically, death is defined as the irreversible cessation of an organism’s overall function. However, certain biological processes, such as organ donation, demonstrate that individual organs, tissues, and cells can persist and remain functional long after an organism has perished. This resilience raises a critical question: What enables some cells to continue functioning beyond the point of death?

Researchers investigating postmortem biological activity have explored how cells can survive and even transform under specific conditions. In a recently published study, it was highlighted that cells, when supplied with oxygen, nutrients, bioelectricity, or biochemical signals, are capable of reorganizing and developing into multicellular entities with novel functions even after death.

The Third State: A New Biological Perspective

The concept of the third state disrupts conventional understandings of cellular behavior. While biological transformations such as a caterpillar becoming a butterfly or a tadpole maturing into a frog follow predetermined pathways, the emergence of entirely new multicellular organisms from dead tissues does not fit into such patterns.

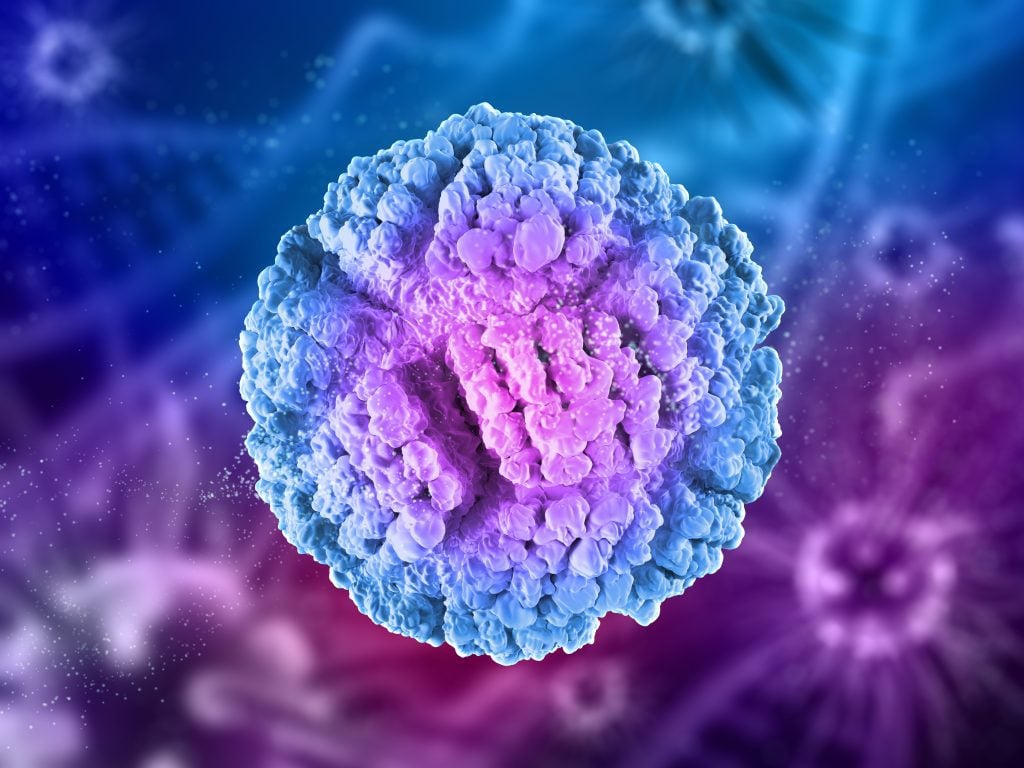

For instance, tumors, organoids, and laboratory-grown cell lines like HeLa cells are excluded from this category because they do not acquire fundamentally new functions. Instead, researchers have found that skin cells taken from deceased frog embryos displayed remarkable adaptability when placed in a petri dish. These cells spontaneously self-organized into multicellular constructs termed xenobots. Unlike their original biological role in frog embryos, these xenobots employed their cilia—tiny, hair-like structures—for locomotion rather than mucus movement.

Even more remarkably, xenobots have demonstrated kinematic self-replication, a process in which they reproduce their form and function without undergoing growth. This form of replication differs from conventional biological reproduction, which typically involves cellular division and expansion.

Further research has revealed that isolated human lung cells can self-assemble into new multicellular constructs known as anthrobots. These anthrobots exhibit behaviors distinct from their original function, displaying movement and even the ability to repair themselves. Additionally, they have been observed assisting damaged neuron cells in their vicinity, suggesting a broader regenerative potential.

The emergence of xenobots and anthrobots raises significant questions about the inherent plasticity of cells. Unlike preprogrammed developmental pathways seen in nature, these cells exhibit a surprising level of autonomy in their organization and functionality. Their ability to adapt to new environments and perform roles beyond their initial biological purpose suggests that the boundaries of cellular potential are more fluid than previously believed.

Furthermore, this third state highlights a unique form of biological resilience. Cells that would ordinarily perish postmortem instead reorganize themselves, demonstrating an ability to respond dynamically to environmental stimuli. This newfound adaptability challenges the traditional dichotomy between life and death, suggesting that biological existence may not be as binary as once assumed.

The discovery also introduces philosophical and ethical considerations. If cells retain the ability to reorganize and form functioning entities after death, what implications does this hold for our understanding of individuality and the continuity of life? Could this redefine how death is perceived, especially in medical and scientific contexts?

Taken together, these findings highlight the extraordinary plasticity of cellular systems and challenge the notion that life evolves through strictly predetermined pathways. The third state implies that organismal death may not signify an absolute end but rather serve as a catalyst for biological transformation. This revelation opens new doors for scientific inquiry, pushing the boundaries of what is known about cellular function, regeneration, and the potential longevity of life beyond conventional limits.

Survival Beyond Death: The Role of Postmortem Conditions

The ability of cells and tissues to remain functional postmortem depends on a variety of factors, including environmental conditions, metabolic activity, and preservation methods.

Survival duration varies among different cell types. For example, in humans, white blood cells can persist for up to 86 hours after death. In mice, skeletal muscle cells have been successfully regrown up to 14 days postmortem. Similarly, fibroblast cells from sheep and goats have been cultured successfully even a month after death.

Metabolic activity plays a crucial role in determining whether cells can continue to function. Cells with high energy demands struggle to survive once nutrient and oxygen supplies cease, whereas those with lower energy requirements have a greater chance of persisting. Cryopreservation techniques have further demonstrated how tissues such as bone marrow can remain viable for extended periods, retaining functionality comparable to that of living donor sources.

Intrinsic survival mechanisms also contribute to cellular longevity. Studies have shown that stress-related and immune-related genes experience heightened activity following death, possibly as a compensatory response to the loss of homeostasis. However, additional factors such as trauma, infection, and time elapsed since death can significantly impact cellular viability.

Moreover, variables like age, health status, sex, and species type influence postmortem cellular behavior. A notable example is seen in the challenges associated with transplanting metabolically active islet cells, which produce insulin in the pancreas. Researchers speculate that immune system responses, high metabolic demands, and the deterioration of protective mechanisms contribute to the frequent failure of islet cell transplants.

While the precise mechanisms that allow certain cells to persist after death remain unclear, one hypothesis suggests that specialized membrane channels and pumps act as intricate electrical circuits, generating signals that facilitate communication, growth, and movement within cellular structures.

Potential Medical and Biological Implications

The implications of the third state extend far beyond theoretical biology, offering potential advancements in medicine and biotechnology.

For instance, anthrobots derived from an individual’s own tissue could serve as highly effective drug delivery vehicles, minimizing the risk of immune rejection. In medical applications, engineered anthrobots could be programmed to remove arterial plaque in patients with atherosclerosis or clear excess mucus in individuals with cystic fibrosis.

Crucially, these multicellular constructs possess a natural lifespan, degrading within four to six weeks. This built-in “kill switch” helps prevent the risk of uncontrolled cell growth, ensuring they remain safe for medical use.

Understanding how certain cells defy death and reorganize into functional multicellular entities holds great promise for personalized and regenerative medicine. By harnessing these biological processes, future therapies may be developed to repair damaged tissues, deliver targeted treatments, and revolutionize approaches to disease management.

The study of this remarkable third state continues to reveal new dimensions of cellular adaptability, blurring the line between life and death. As scientific exploration advances, the potential for unlocking transformative medical innovations becomes increasingly evident.