The Small Round Scar on Your Arm

If you grew up in Asia, Africa, Latin America, or parts of Eastern Europe, there is a strong chance you carry a small, round scar on your upper arm.

It is usually about the size of a coin. Slightly sunken into the skin. Sometimes darker or lighter than the surrounding area.

Many people only become aware of it years later—while changing clothes, swimming, or noticing it in old photographs. And almost inevitably, the same question appears:

“Where did this come from?”

For some, the scar becomes a quiet source of embarrassment. Others remember being teased about it as children. Many create their own explanations—an old injury, a childhood illness, or a burn—because no one ever explained the real reason.

That tiny mark has carried decades of confusion, stigma, and misinformation across entire generations.

Below are five of the most common misconceptions about the round scar on the arm—and the deeper truth behind each one.

Misconception #1: “It’s a skin disease or a childhood injury”

This is one of the most widespread assumptions. People often believe the scar came from a boil, a skin infection, chickenpox complications, or an injury they cannot remember clearly. Some even think it was caused by a burn or a wound that healed badly.

The deeper truth:

In most cases, this scar is caused by the BCG vaccine, which was developed to protect against tuberculosis (TB)—a disease that once killed millions and devastated entire communities.

The vaccine is usually given in infancy or early childhood. Because it happens so early in life, most people have no memory of the injection or the healing process. The moment disappears from memory, but the mark remains on the skin.

The scar is intentional, not accidental. The BCG vaccine is injected just under the skin rather than deep into the muscle. This creates a localized immune reaction, sometimes forming a small ulcer that eventually heals into a permanent scar.

Nothing went wrong.

The body responded exactly as it was designed to.

Misconception #2: “Only people from poor or rural backgrounds have it”

In some societies, the scar has been unfairly associated with poverty, rural living, or outdated healthcare. As a result, people who have it may feel judged or labeled.

The deeper truth:

The BCG vaccine was introduced through national public health programs, not because families were poor, but because tuberculosis was widespread and deadly.

At different points in history, countries across Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America vaccinated entire generations of children—regardless of social class. Wealthy families, city residents, and even the children of government officials received the same vaccine.

The scar reflects public health priorities of a specific era, not personal circumstances. It says nothing about hygiene, intelligence, or social status.

Misconception #3: “If you don’t have the scar, you weren’t vaccinated”

People often compare arms with siblings or friends and assume the scar is proof of vaccination. This can cause confusion and even family disputes.

The deeper truth:

Not everyone who receives the BCG vaccine develops a visible scar.

Scar formation depends on several factors, including:

-

Individual immune response

-

Skin type and healing patterns

-

Injection technique

-

Age at vaccination

-

Aftercare and environmental exposure

Some people heal with barely any mark at all. Others develop a noticeable scar that fades significantly over time.

In simple terms:

-

No scar does not mean no vaccine

-

A scar does not mean stronger immunity

-

Only medical records can reliably confirm vaccination

Misconception #4: “The scar means your immune system is weak or damaged”

This belief creates genuine fear for some people. They worry the scar signals an immune defect or a long-term health problem.

The deeper truth:

The BCG scar is actually evidence of a normal and healthy immune response.

When the vaccine enters the body, the immune system recognizes the weakened bacteria and launches a defense. This process may involve redness, swelling, and the formation of a small lesion that later heals into a scar.

Researchers have even studied how early vaccines like BCG may help “train” the immune system to respond more effectively to other infections later in life.

The scar is not damage.

It is a record of immune activity, not a sign of weakness.

Misconception #5: “It’s dangerous or should be removed”

Because the scar is visible and sometimes textured, some people worry it could grow, spread, or become harmful over time.

The deeper truth:

The BCG scar is completely harmless.

-

It does not spread

-

It does not turn into cancer

-

It does not indicate illness

Doctors consider it a benign, permanent mark—similar to any healed childhood scar. There is no medical reason to remove it unless someone chooses cosmetic treatment for personal reasons.

From a health perspective, it requires no care or monitoring at all.

Why No One Ever Explained It

For many families, especially in past decades, vaccination was routine and unquestioned. Parents were simply told, “Bring your child,” and they complied.

There were no long explanations and no follow-up discussions years later.

Children grew up protected—but uninformed.

As healthcare systems modernized, communication improved. Yet the silence surrounding this small scar remained. Entire generations carried the mark without knowing its origin.

A Small Scar with a Big History

That small round scar is not a flaw.

It is not a disease.

It is not a sign of hardship or neglect.

It is a quiet reminder of a time when infectious diseases shaped national policy—and when prevention often arrived long before understanding.

For millions of people, it represents early protection given without ceremony or explanation.

Sometimes, the smallest marks carry the longest stories.

News in the same category

10 Early Warning Signs of Breast Cancer You Should Never Ignore

Don’t Throw Away Lemon Seeds: The Natural Treasure Almost Everyone Wastes

Fatty Liver: Symptoms, Types, Causes, and Treatment

If you have bumps on your tongue, your body is trying to tell you something very important

Stop urinating at night: eat bananas this way

Why we shouldn't leave our bedroom door open while we sleep: Safety and Energy

The 5 Foods That May Silently “Feed” a Tumor-Friendly Environment

🔍 3 Intimate Habits That May Increase Cervical Cancer Risk—And What Loving Couples Can Do to Protect Each Other

Save your child's 'baby teeth', they are a goldmine of stem cells

Say Goodbye to High Blood Sugar: Discover the Power of Guava

The part of the body that suffers the most when you keep quiet about what you feel

Could These Two Everyday Vegetables Help Support Collagen in Your Knees and Promote Joint Comfort?

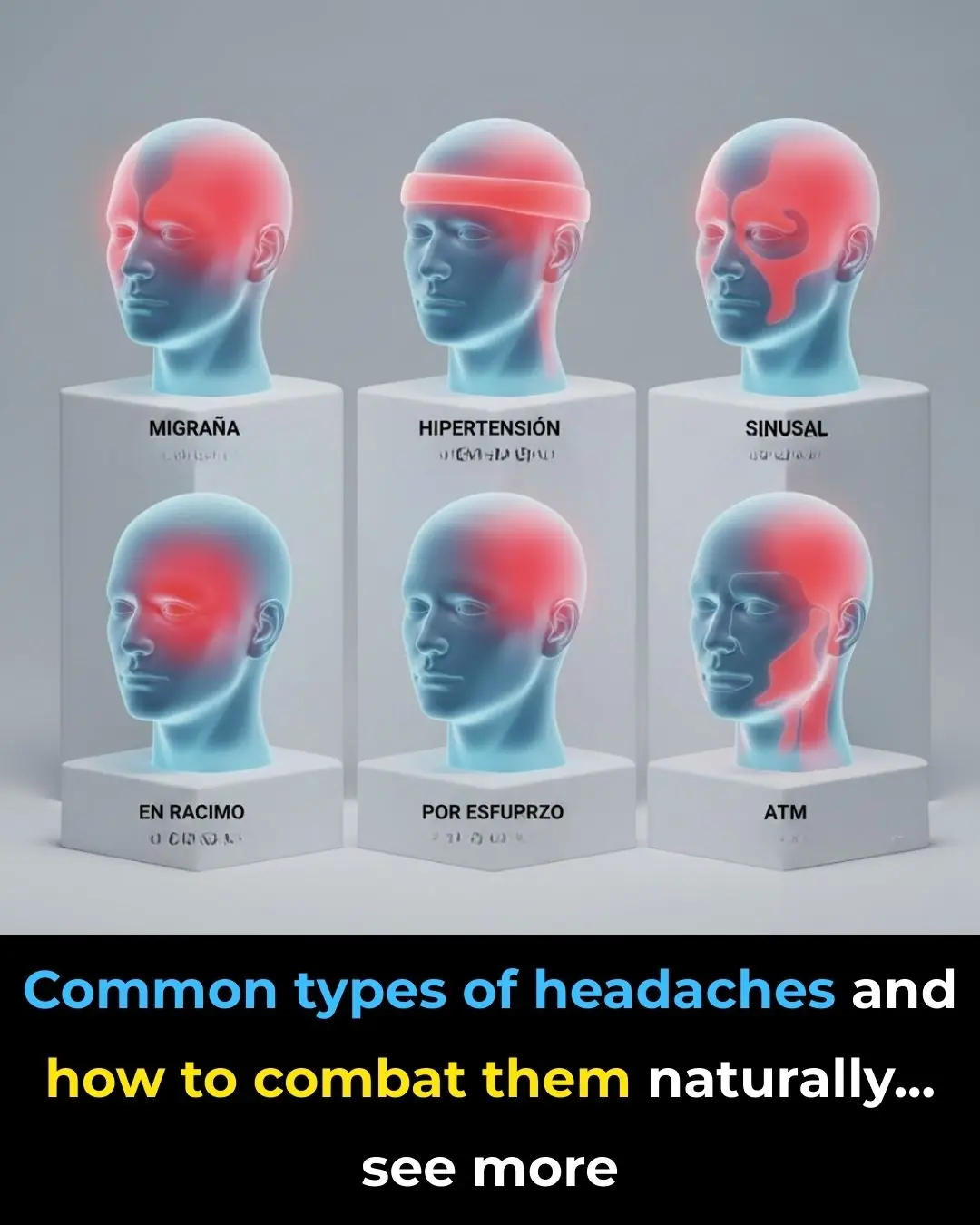

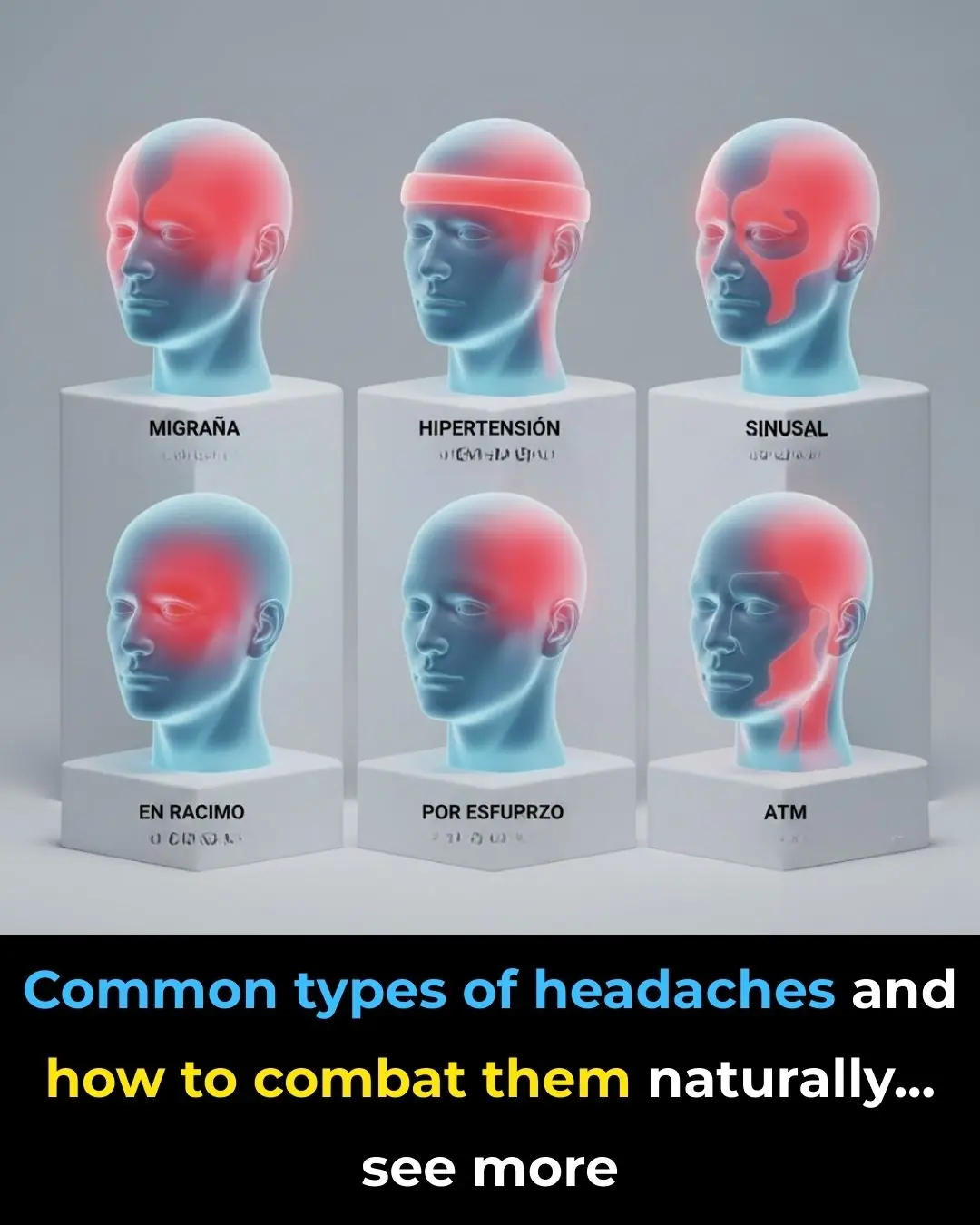

Lavender lemonade to soothe headaches and anxiety

The Best Foods for Stronger Nails After 40

Keeping Your Legs Up Against the Wall for 5 Minutes a Day: Real Benefits for Your Body

Cabbage Is Good for You

Drinking a Glass of Water Before Bed May Help Reduce the Risk of Stroke and Heart Attack

Dark Chocolate May Be Better for Your Heart Than Green Tea, Study Finds

News Post

Control Blood Sugar, Arthritis, Cholesterol, Poor Circulation, Fatty Liver & More With This Natural Remedy

10 Early Warning Signs of Breast Cancer You Should Never Ignore

HER FATHER’S TATTOO

Don’t Throw Away Lemon Seeds: The Natural Treasure Almost Everyone Wastes

A Boy’s Screams Were Ignored Until It Was Almost Too Late

“My Company Is Gone.” The Billionaire Lost Everything in One Day… Until the Poor Janitor Changed Everything

They Bullied a New Black Kid — Then 10 Bikers Showed Up at the School Gate.

I Sent Money Every Month — My Daughter Never Saw a Dollar

Six Oils That May Support Your Arteries and Circulation

Fatty Liver: Symptoms, Types, Causes, and Treatment

If you have bumps on your tongue, your body is trying to tell you something very important

Stop urinating at night: eat bananas this way

Why we shouldn't leave our bedroom door open while we sleep: Safety and Energy

The 5 Foods That May Silently “Feed” a Tumor-Friendly Environment

🔍 3 Intimate Habits That May Increase Cervical Cancer Risk—And What Loving Couples Can Do to Protect Each Other

Save your child's 'baby teeth', they are a goldmine of stem cells

Say Goodbye to High Blood Sugar: Discover the Power of Guava

The part of the body that suffers the most when you keep quiet about what you feel

Could These Two Everyday Vegetables Help Support Collagen in Your Knees and Promote Joint Comfort?