The Tiny Bacterium That Turns Toxic Metal Into Pure 24-Karat Gold

For most of us, gold is something we imagine locked away in jewelry stores or buried deep underground—certainly not forming quietly in polluted soil. Yet scientists have discovered a tiny bacterium, Cupriavidus metallidurans, that thrives in places loaded with toxic metals and, astonishingly, transforms some of that metal into pure 24-karat gold. It does not do this to make treasure, nor is it a biological shortcut to getting rich. Instead, this strange ability is pushing researchers to rethink what life is capable of in the harshest environments.

From industrial waste to old electronics, the story of this microbe connects our hunger for technology, the pollution it leaves behind, and a surprising kind of natural “alchemy” unfolding completely out of sight.

Meet the “Midas Microbe”

While humans spent centuries chasing mythical alchemy in laboratories, nature quietly achieved its own version in contaminated soil and industrial sludge. In these extreme habitats—so toxic that most organisms die within minutes—Cupriavidus metallidurans survives and even thrives. First identified in 1976 in the sludge of a zinc decantation tank in Belgium, the microbe has evolved to cope with exactly the kind of metal contamination humans have been releasing for decades.

Despite sensational headlines, this bacterium doesn’t “eat” gold or use it as fuel. In fact, gold is a chemical nuisance. In gold-rich soils, dissolved gold ions mix with ions of metals such as copper. Copper is essential for the microbe’s metabolism, but gold ions disrupt the same biochemical pathways, turning something life-sustaining into a toxic threat.

To survive, C. metallidurans activates a sophisticated defense system. Instead of fleeing from metal-rich environments, it chemically transforms dissolved, reactive gold into inert, solid gold that can no longer interfere with its internal chemistry. Over time, tiny particles of gold accumulate on and around the cell.

This is not treasure-making—it’s a detox strategy. But in perfecting this strategy, the microbe occupies ecological niches too extreme for most life forms. And in the process, it plays an unexpected role in how gold moves, concentrates, and even forms natural deposits in the environment.

How a Bacterium Turns Poison Into 24-Karat Gold

If the first half of the story is about biological survival, the second is about stunning biochemical precision. Cupriavidus metallidurans doesn’t just neutralize gold in a vague way; it manages a carefully tuned system that researchers have mapped in detail, particularly through the groundbreaking work of geomicrobiologist Frank Reith.

When dissolved gold and copper ions enter the cell, they trigger specialized “gold-induced genes,” collectively called the Gig cluster. At the same time, a plasmid-borne system featuring the enzyme CopA springs into action. CopA functions as an oxidase within the periplasm—the narrow space between the cell’s inner and outer membranes.

Here, gold complexes in a reactive ionic form are stripped of electrons and converted into elemental, metallic gold—the same form used in jewelry. As this happens, the gold accumulates as nanoparticles either in the periplasm or on the cell surface, where it can no longer disrupt metabolism.

Repeated cycles of this detoxification can coat the bacterium so thoroughly that it becomes encapsulated in a fragile, gold-lined shell known as a bacteriomorph. Remarkably, the gold is extremely pure. While natural gold deposits are often mixed with silver or other metals, C. metallidurans refines gold to more than 99% purity.

At the molecular level, this microbe is not simply surviving. It is performing a targeted, highly selective form of chemical refinement that rivals industrial processing in precision.

Nature’s Hidden Gold Nugget Factories

For centuries, gold nuggets were assumed to be purely geological artifacts—formed deep underground, then slowly exposed by erosion. But new microscopic studies have complicated that traditional story. When scientists looked closely at gold grains, they found something surprising: many were covered with living biofilms made of bacteria. And among these microbes was Cupriavidus metallidurans.

While high-temperature gold veins form deep below the surface, the “secondary” gold found in soils and streams often bears clear signs of biological involvement. As groundwater percolates through mineral-rich rock, it picks up tiny quantities of dissolved gold. Microbes like C. metallidurans act as microscopic anchors. Each cell detoxifies gold, leaving behind a nanoparticle. Over years, decades, or centuries, these particles clump together into visible nuggets—the kind people pan from rivers.

The microbe rarely works alone. It shares its habitat with Delftia acidovorans, another gold-resistant species with a very different strategy. C. metallidurans pulls gold inside or onto the cell and converts it there, while Delftia produces a molecule called delftibactin, which binds and solidifies gold outside the cell. Together, they help turn invisible dissolved gold into the solid metal found in nature.

What appears to be simple geology is, in part, the long-term result of microbial survival instincts—life shaping mineral deposits one nanoparticle at a time.

From Neo-Alchemy to Urban Mining

Once scientists realized that C. metallidurans could turn toxic gold compounds into 24-karat metal, engineers, environmental researchers, and even artists began asking: What could humanity do with this ability?

In 2012, artist Adam Brown and microbiologist Dr. Kazem Kashefi debuted an installation called “The Great Work of the Metal Lover.” Inside a gallery, they ran a bioreactor that converted gold chloride—a toxic, acidic compound—into delicate sheets of gold. The artwork functioned as both a science demonstration and a philosophical statement, asking viewers to reconsider the boundaries between waste and value.

Industry has taken the idea further. Modern electronic waste is astonishingly rich in precious metals. A ton of discarded circuit boards can contain more gold than many traditional ore deposits, yet extracting it through smelting is energy-intensive and environmentally devastating.

Companies such as Mint Innovation are developing bio-refining technologies that mirror what C. metallidurans does in nature. Circuit boards are shredded, the metals are dissolved into a solution, and specialized microbes are introduced to selectively pull gold out. Because the process operates at or near room temperature, it avoids the extreme heat, toxic emissions, and chemical waste generated by conventional smelting.

A new facility planned by Mint Innovation in Texas is expected to process millions of pounds of circuit boards annually, recovering valuable metals that would otherwise end up in landfills. In this model, discarded electronics become a form of “urban ore,” and microbes become microscopic refinery workers helping transform yesterday’s devices into tomorrow’s raw materials.

Rethinking Gold, Waste, and Our Partnership With Nature

The story of Cupriavidus metallidurans is not really about effortless gold production—it is about how life survives in the hostile environments we create. In nature, the bacterium turns something toxic into something stable. In human hands, the same biochemical trick becomes a blueprint for turning waste into reusable resources and for shifting from an extractive mindset to a regenerative one.

It also reminds us that innovation doesn’t always need to be loud, high-tech, or energy-hungry. Sometimes it looks like a microscopic organism performing quiet chemistry in the dark, using elegance instead of force.

For the rest of us, the lesson is not about striking it rich. It’s about rethinking what we call “waste.” Old phones, laptops, and circuit boards are not useless junk—they are concentrated reservoirs of metals that were costly to mine, refine, and transport. Choosing responsible recycling options, repairing devices rather than replacing them, and supporting policies that promote resource recovery are not abstract environmental ideals. They are practical steps inspired by a microscopic metallurgist that shows us even our most problematic byproducts can become valuable resources—if we choose to work with nature instead of against it.

News in the same category

Golden Snub-Nosed Monkeys: A Glimpse of Wild Beauty in the Misty Mountains of China

Understanding the Extended Recovery Journey After Pregnancy

4 Things You Should Never Throw Away After a Funeral — And Why They Matter More Than You Realize

After Almost a Decade, Tennessee Zoo Celebrates Arrival of Newborn Gorilla

"EV Battery Longevity: How Modern Electric Vehicle Batteries Are Built to Last Up to 20 Years

Breakthrough Study Reveals COVID Vaccines Reduce Heart Attacks and Strokes

California Becomes the Fourth-Largest Economy in the World, Surpassing Japan in Nominal GDP

H5N1 Outbreak Causes Devastating Mortality in World's Largest Elephant Seal Colony

The Loneliest House in the World: The Fascinating Story of Elliðaey Island's Remote Lodge

Breakthrough in HIV Cure: Stem Cell Transplant Leads to HIV Remission Without CCR5-Δ32 Mutation

Study Reveals When You Focus on the Good, Your Brain Literally Rewires Itself to Look for More Good – That’s the Magic of Neuroplasticity

Trump just revealed the exact date for $2,000 checks — is yours coming before christmas?

How Dan Price’s Bold Pay Cut Transformed Gravity Payments and Sparked a Wage Revolution

Portugal Enforces Groundbreaking ‘Right to Disconnect’ Law Protecting Workers’ Off-Hours

15-Year-Old Belgian Prodigy Laurent Simons Earns PhD in Quantum Physics, Redefining Academic Limits

Revolutionary Contact Lenses Enable Humans to See in the Dark Using Infrared Technology

Woman Breaks Into Shelter to Save Her Pit Bull From Euthanasia, Sparking National Debate

A Little Dog, a Big Moment: The Puppy That Captured Hearts at the Pope’s Parade

News Post

The Daily Drink That Helps Clear Blocked Arteries Naturally

12 Benefits of Bull Thistle Root and How to Use It Naturally

8 Warning Signs of Colon Cancer You Should Never Ignore

Explore Canada from Coast to Coast by Train for Just $558 🇨🇦: A 3,946-Mile Adventure Through Stunning Landscapes

Golden Snub-Nosed Monkeys: A Glimpse of Wild Beauty in the Misty Mountains of China

Understanding the Extended Recovery Journey After Pregnancy

Study: nearly all heart attacks and strokes linked to 4 preventable factors

4 Things You Should Never Throw Away After a Funeral — And Why They Matter More Than You Realize

Stop adding butter — eat these 3 foods instead for faster weight loss

Chicken Eggs with Mugwort: Highly Beneficial but Certain People Should Avoid Them

Watercress: The World’s Top Anti-Cancer Vegetable You Can Find in Vietnamese Markets

4 Plants That Snakes Absolutely Love — Remove Them Immediately to Keep Your Home Safe

The 4 “Golden Hours” to Drink Coffee for Maximum Health Benefits — Cleaner Liver, Better Digestion, Sharper Mind

Don’t Rip This Out — Treat It Like Gold Instead. Here’s Why.

Say Goodbye to Bare Branches: Revive Your Christmas Cactus Blooms with These Expert-Backed Hacks

Were You Aware of This? A Surprisingly Simple Spoon Trick Can Stop Mosquito Bite Itching

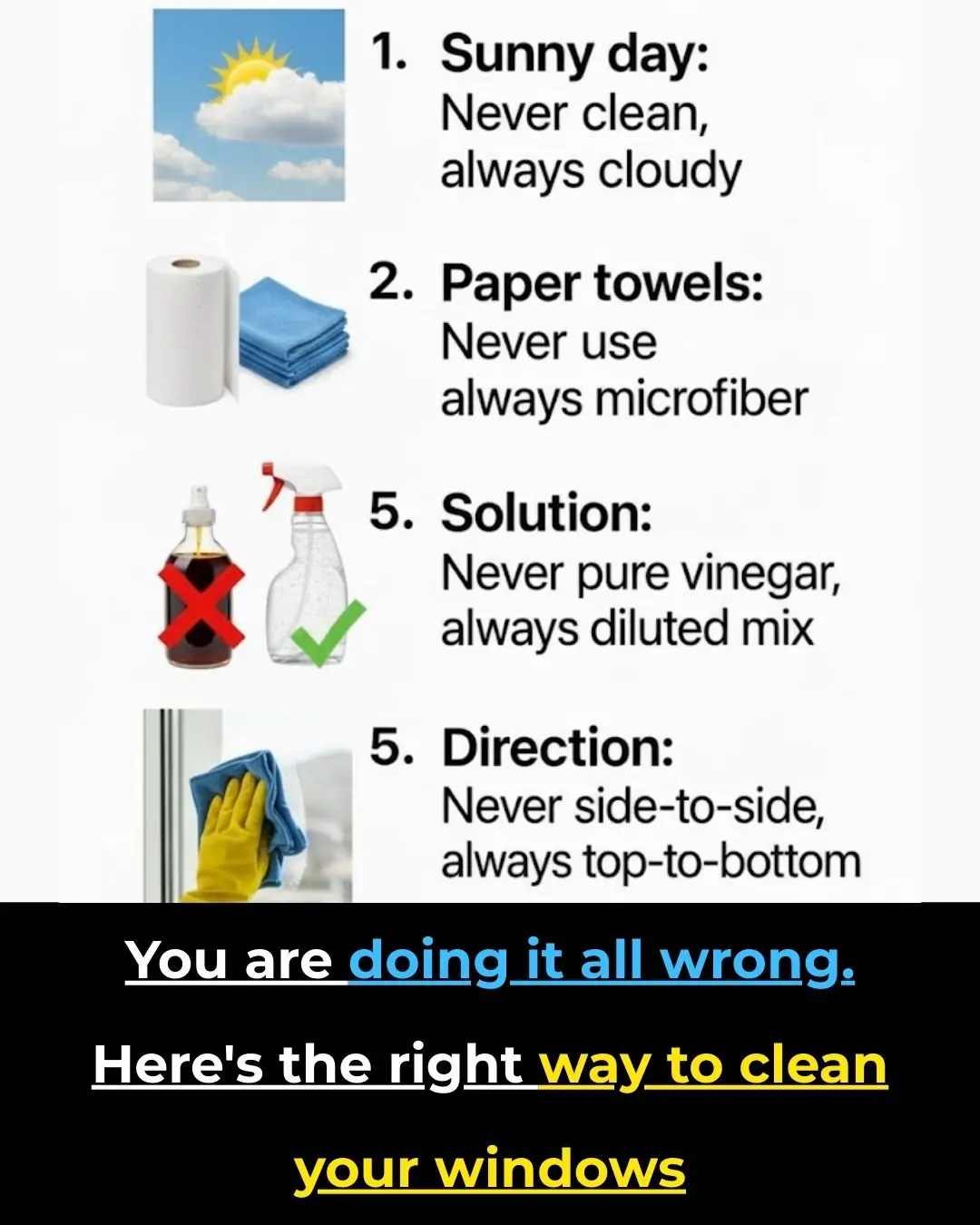

You’re Doing It All Wrong — Here’s the Right Way to Clean Your Windows

After Almost a Decade, Tennessee Zoo Celebrates Arrival of Newborn Gorilla