Why drinking your sugar is more harmful for diabetes than eating it, study finds

Groundbreaking research from Brigham Young University (BYU), conducted in partnership with several leading German research institutions, has revealed compelling evidence that drinking sugar, particularly through sodas and even fruit juices, substantially increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. In contrast, sugars consumed from solid foods do not appear to carry the same danger — and in some cases, may even provide a slight protective effect.

This finding upends decades of common assumptions about sugar consumption, urging both health experts and the general public to rethink how sugar’s form — liquid vs. solid — affects our metabolic health.

The Hidden Dangers of Liquid Sugar

A massive analysis involving data from over half a million people worldwide uncovered a striking difference in how the body metabolizes sugar depending on whether it’s consumed as a drink or a solid food.

Key findings include:

-

Each additional daily serving of a sugar-sweetened beverage—such as soda, sports drinks, or energy drinks—was associated with a 25% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

-

Even fruit juice, which many perceive as a healthy option, carried a 5% increased risk per additional 8-ounce serving.

-

The association was dose-dependent, meaning the risk began to rise from the very first sugary drink consumed daily.

Dr. Karen Della Corte, the study’s lead author and a professor of nutritional science at BYU, noted:

“This is the first research to clearly demonstrate a dose-response relationship between different sugar sources and type 2 diabetes risk. It emphasizes that drinking your sugar, whether it comes from soda or juice, poses a much greater threat to health than eating it.”

Why Liquid Sugar Hits Harder

The reason liquid sugars are more harmful lies in how rapidly they are absorbed by the body. Beverages deliver a high concentration of sugar directly into the bloodstream, forcing the liver to process it all at once. This sudden overload promotes fat accumulation, insulin resistance, and inflammation—all key drivers of metabolic disease.

In contrast, solid foods containing sugar usually come with fiber, protein, or other nutrients that slow digestion and moderate blood sugar spikes. This natural buffering effect explains why eating a sweet snack can have a far milder metabolic impact than drinking a soda of equivalent sugar content.

Moreover, studies show that liquid calories don’t trigger the same feelings of fullness as solid foods, meaning people often consume more calories overall when drinking sugary beverages. Over time, this contributes to weight gain, a major risk factor for diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Fruit Juice: The Misleading “Healthy” Choice

Although fruit juice contains vitamins and antioxidants, it is not nutritionally equivalent to eating whole fruit. When fruit is juiced, its fiber—the very component that slows sugar absorption—is removed, leaving behind a concentrated source of natural sugars that can cause sharp spikes in blood glucose.

Whole fruits, on the other hand, contain fiber and phytochemicals that help stabilize blood sugar, improve gut health, and reduce inflammation. These differences explain why eating fruit tends to reduce diabetes risk, while drinking fruit juice can increase it.

As Della Corte emphasized:

“Fruit juice, even when it contains vitamins, shouldn’t be seen as a healthy substitute for whole fruit. Concentrated liquid sugars, even from natural sources, can substantially harm metabolic health.”

Rethinking Public Health Guidelines

This research highlights the urgent need to update dietary guidelines to reflect the differences between liquid and solid sugar sources. For years, most public health recommendations have grouped all added sugars together, but this study shows that not all sugars are created equal.

Using advanced dose-response modeling, the researchers provided robust evidence that sugary drinks—including fruit juice—should be specifically targeted in public health campaigns aimed at reducing diabetes and obesity.

Della Corte concluded:

“Our results point to the necessity of stronger, clearer guidance against sugar-sweetened beverages. Future dietary advice should focus on reducing harmful liquid sugars instead of broadly condemning all sugar intake.”

The Bigger Picture: Preventing a Global Diabetes Crisis

With type 2 diabetes rates rising worldwide, understanding the nuanced relationship between diet and disease risk is more important than ever. The findings from this study not only offer new insight into how sugar impacts metabolism but also empower individuals to make smarter dietary choices.

Reducing sugary drink consumption—even by one serving a day—could have a major cumulative impact on public health, lowering rates of diabetes, heart disease, and obesity.

Ultimately, the message is clear: It’s not just how much sugar you consume, but how you consume it that matters most for your long-term health.

News in the same category

Thyme Essential Oil Shows Signs of Killing Lung, Oral and Ovarian Cancer

How to cleanse your kidneys using this natural, home made drink

Science backs it up: 3 fruits that fight liver fat, regulate sugar and cholesterol

People whose mouths feel dry when sleeping at night need to know these 8 reasons

Scientists explain shocking reality of what your brain sees right before you die

Neurologist Advises Ceasing Beer Consumption by Age 65

Drinking Water on an Empty Stomach: Japanese Water Therapy, What Science Says, and More

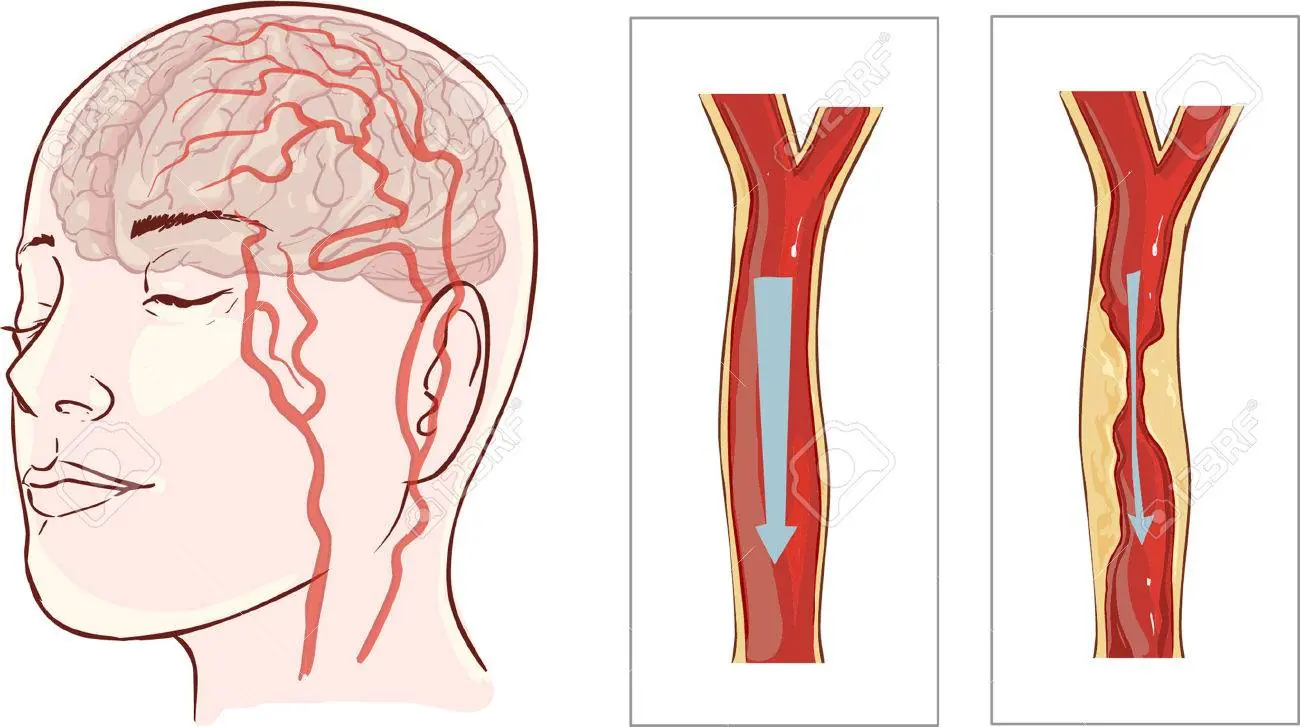

Eat This — It Opens Arteries to Your Heart and Brain

Eat this before bed? Doctors are stunned by the results

The Vitamin and Tea Combo Linked to Alzheimer’s Protection

The 7 Silent Causes of Poor Leg Circulation — And How to Fix Them Naturally

Early Signs of Kidney Disease & How to Protect Your Kidneys (Evidence Based)

1 cup a day takes joint pain away naturally

Feeling sluggish after meals? 7 natural ways to improve bile flow and boost digestion

Don’t ignore these 12 bizarre signs you need more vitamin B1!

Orange & Ginger Cleanse Juice for Kidneys, Lungs & Liver

Thyme: The Natural Remedy for a Variety of Health Problems

Red Onion for Instant Blood Sugar Drop: A Kitchen Secret Few Know

News Post

Warning Signs You Should Never Ignore: The Silent Symptoms of a Brain Aneurysm

Model Loses Both Legs After Toxic Shock Syndrome From Everyday Tampon Use

Before And After: Woman With Extreme Lip Enhancements Reveals Old Look

Tragic End: Georgia O’Connor Passes Away Weeks After Wedding Amid Medical Neglect

DIY Survival Water Filter: A Simple Life-Saving Tool You Can Make Anywhere

30 Powerful Reasons You Should Stop Ignoring Purslane

You are doing it all wrong. Here’s the right way to store leftovers

When a cat rubs against you, this is what it means

Zodiac Signs Most Likely to Have Prophetic Dreams

Ivy and Vinegar: A Safe and Natural Spray to Keep Pests Off Your Garden

Garlic, Honey, and Cloves – a powerful natural remedy packed with health benefits

Vinegar is the key to streak-free windows and shiny surfaces, but most use it wrong. Here's the right way to use it

Haven't heard that before

You are doing it all wrong. Here’s the right way to store leftovers

10 genius tricks to revive your garden patio

You are doing it all wrong. Here’s the right way to wash towels

They look so harmless

How to Remove a Fish Bone from Your Throat 🐟😮