Affectionate Touch, Oxytocin, and Women’s Stress and Cardiovascular Health

Human touch is a fundamental biological signal, yet only in recent decades has its measurable impact on physiology been systematically studied. Among different forms of touch, affectionate partner contact—such as hugging, cuddling, and close physical intimacy—has emerged as a powerful modulator of stress and cardiovascular function, particularly in women. Scientific evidence from psychophysiological and endocrine research demonstrates that these forms of contact are not merely emotionally comforting, but are associated with clear, quantifiable changes in hormones, nervous system activity, and heart health.

One of the most influential early studies in this area was conducted by Light and colleagues and published in Biological Psychology. This research focused on premenopausal women and examined how the frequency of partner affection related to physiological markers of stress and cardiovascular regulation. The investigators found that women who reported more frequent partner hugging and cuddling had significantly higher circulating levels of oxytocin, a neuropeptide central to social bonding and emotional regulation. At the same time, these women exhibited lower resting blood pressure and heart rate—two key indicators of cardiovascular risk.

Oxytocin plays a direct mechanistic role in these effects. Often referred to as the “bonding hormone,” oxytocin is released in response to social touch, intimacy, and trust. Beyond its social functions, oxytocin acts on the autonomic nervous system to suppress sympathetic (“fight-or-flight”) activity while enhancing parasympathetic (“rest-and-digest”) tone. This shift results in reduced vascular resistance, slower heart rate, and lower blood pressure. The findings reported by Light et al. therefore provided one of the first demonstrations that affectionate partner contact may contribute to cardiovascular protection in women through a biologically identifiable hormonal pathway (Biological Psychology, Light et al.).

More recent research has reinforced and extended these conclusions using experimental stress paradigms. A 2022 study published in PLOS ONE investigated whether physical affection could buffer the body’s response to acute psychological stress. In this study, participants were exposed to a standardized stress-inducing task after either engaging in affectionate contact with their romantic partner (such as hugging or cuddling) or receiving no such contact. Researchers measured cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone, which rises in response to perceived threat and contributes to long-term cardiovascular and metabolic disease when chronically elevated.

The results showed that women who hugged or cuddled their partner prior to the stress task exhibited a significantly blunted cortisol response compared with women who did not receive affectionate contact. In other words, their bodies released less cortisol in response to stress, indicating a dampened activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Notably, this stress-buffering effect was substantially stronger in women than in men, suggesting a sex-specific biological sensitivity to affectionate touch (PLOS ONE, 2022).

This sex difference is consistent with broader evidence that women’s stress physiology is more tightly linked to social context and affiliative behavior. Evolutionary and neuroendocrine models propose that, alongside the classic “fight-or-flight” response, women may rely more heavily on a “tend-and-befriend” strategy under stress, mediated in part by oxytocin. Affectionate partner contact appears to activate this pathway, reducing cortisol output and limiting the downstream cardiovascular strain associated with repeated stress exposure.

The implications of these findings are clinically and socially meaningful. Chronic stress and elevated cortisol contribute to hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. By lowering blood pressure, heart rate, and stress hormone release, regular affectionate contact may serve as a low-cost, non-pharmacological factor supporting long-term heart health in women. Importantly, these effects are not explained solely by psychological perception; they are reflected in objective biomarkers measured in controlled studies.

It is essential to note that this research is correlational and experimental rather than interventional in a medical sense. While affectionate touch is associated with better physiological outcomes, it is not a substitute for medical treatment of cardiovascular disease or anxiety disorders. Nonetheless, the consistency of findings across studies, combined with clear biological mechanisms involving oxytocin and cortisol, strengthens the conclusion that affectionate partner contact has genuine health relevance.

In conclusion, scientific evidence demonstrates that cuddling and affectionate partner contact confer measurable benefits for women’s stress regulation and cardiovascular health. Studies published in Biological Psychology and PLOS ONE show that such contact increases oxytocin, lowers blood pressure and heart rate, and significantly reduces cortisol responses to stress—effects that are particularly pronounced in women. Together, these findings highlight affectionate touch not merely as an emotional comfort, but as a biologically meaningful contributor to women’s long-term health and resilience.

News in the same category

11 Health Warnings Your Fingernails May Be Sending

Bloated Stomach: 8 Common Reasons and How to Treat Them (Evidence Based)

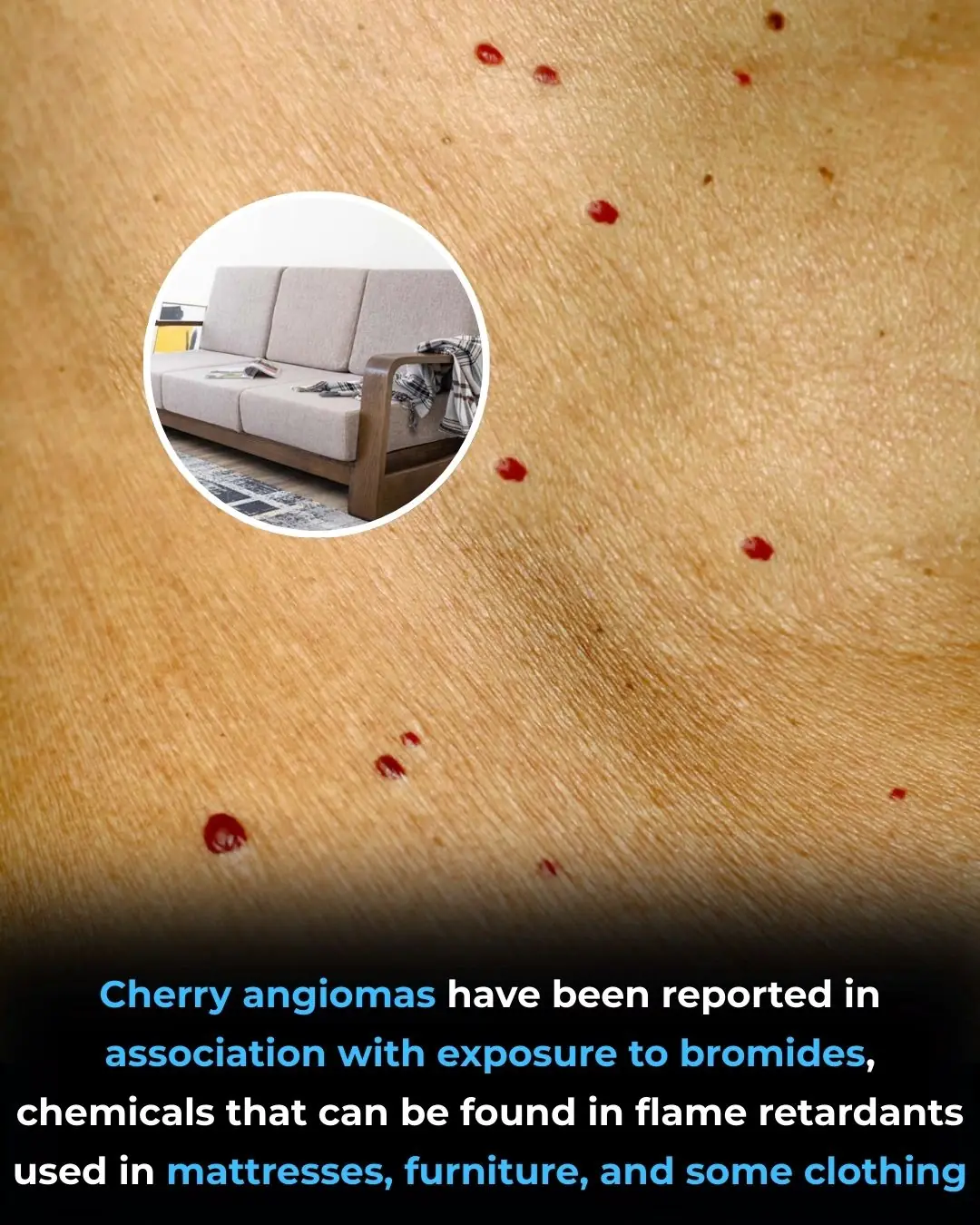

Occupational Bromide Exposure and the Development of Multiple Cherry Angiomas: Insights from a Case Report

How to Use Castor Oil to Regrow Eyelashes and Eyebrows

Three-Dimensional Video Gaming and Hippocampal Plasticity in Older Adults

Raw Cabbage Juice and Rapid Healing of Peptic Ulcers: Early Clinical Evidence from Stanford

Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice as a Supportive Dietary Intervention in Ulcerative Colitis

Anemia: A Lesser-Known Side Effect of GLP-1 Receptor Agonists?

Can Gray Hair Be a Sign That the Body Is Eliminating Cancer Cells?

A 95-Year-Old Cancer Expert with 60 Years of Research Reveals: Four Things You Must Avoid to Keep Cancer from Knocking on Your Door

Clinical Trials Show Meaningful Progress in Pancreatic Cancer Treatment

Medicinal Health Benefits of Garlic (Raw, Supplement) – Science Based

Colon Cleansing: How to Naturally Flush Your Colon at Home (Science Based)

7 Warning Signs of Lung Cancer You Shouldn’t Ignore

After a Stroke, Women Struggle With Daily Tasks for Longer Than Men

What causes night cramps and how to fix the problem

Bee Propolis and Infertility in Endometriosis: Evidence from a Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial

Thymoquinone and Breast Cancer Cell Suppression: Evidence from Preclinical Research

News Post

Even old, non-stick pans can be "revived" with just a few simple tips that everyone should know.

When buying oranges, look here: the bigger they are, the sweeter they are, so grab them quickly!

Tips for making sticky rice that cooks quickly without soaking the rice overnight, resulting in plump grains that remain soft and chewy even after a while.

10 signs you're not drinking enough water

Vinegar Consumption and Reduced Risk of Calcium Oxalate Kidney Stones: Evidence from a Pilot Human Study

11 Health Warnings Your Fingernails May Be Sending

Bloated Stomach: 8 Common Reasons and How to Treat Them (Evidence Based)

Occupational Bromide Exposure and the Development of Multiple Cherry Angiomas: Insights from a Case Report

How to Use Castor Oil to Regrow Eyelashes and Eyebrows

Three-Dimensional Video Gaming and Hippocampal Plasticity in Older Adults

Raw Cabbage Juice and Rapid Healing of Peptic Ulcers: Early Clinical Evidence from Stanford

Montmorency Tart Cherry Juice as a Supportive Dietary Intervention in Ulcerative Colitis

DIY Flaxseed Gel Ice cubes for Clear Skin & Large Pores

Garlic and Honey for Cold, Cough & Acne

Beetroot Ice cubes for Glowing Skin

AN HOUR BEFORE THE CEREMONY, I OVERHEARD MY FIANCÉ WHISPER TO HIS MOM: ‘I DON’T CARE ABOUT HER—I ONLY WANT HER MONEY.’

AFTER 10 YEARS OF MARRIAGE, MY HUSBAND FOUND HIS ‘TRUE LOVE,’ HE SAYS. SHE’S DOWN-TO-EARTH AND DOESN’T CARE ABOUT MONEY. I JUST LAUGHED, CALLED MY ASSISTANT, AND SAID, ‘CANCEL HIS CREDIT CARDS, CUT OFF HIS MOTHER’S MEDICATION, AND CHANGE THE L

I had just landed, suitcase still in my hand, when I froze. There he was—my ex-husband—holding his secretary like they belonged together. Then his eyes met mine.