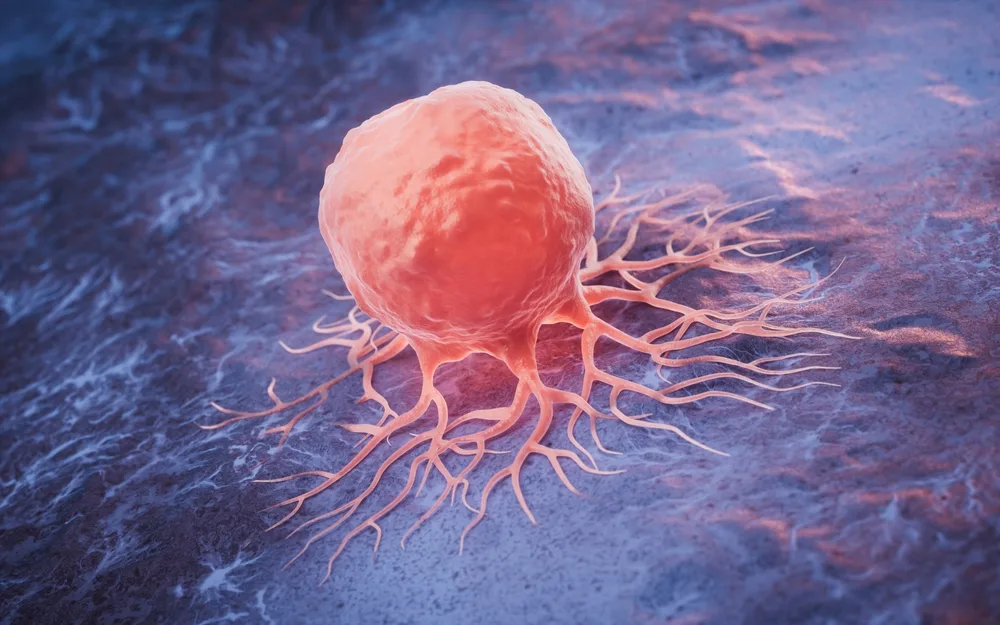

A Universal Cancer Vaccine May Finally Be Within Reach

Cancer vaccines have long carried a frustrating limitation. Unlike flu shots or childhood vaccines that can be mass-produced for millions, most cancer vaccines must be custom-built for each individual patient. Doctors first have to extract tumor samples, analyze their genetic makeup, and then design a vaccine that matches that specific cancer. By the time this complex process is complete, months may have passed—and the cancer may have already evolved into a form the vaccine can no longer recognize.

Now, a research team at the University of Florida believes it may have found a way around this obstacle. Instead of targeting a specific cancer protein, their experimental mRNA vaccine works by broadly activating the immune system, pushing it to recognize and attack tumors on its own. Results from mouse studies, published on July 18, 2025, in Nature Biomedical Engineering, were strong enough that early-stage human trials are already underway.

Dr. Elias Sayour, a pediatric oncologist at UF Health and the study’s lead investigator, sees enormous potential in a cancer vaccine that is ready to use immediately. Rather than waiting months for a personalized therapy, doctors could administer an off-the-shelf vaccine as soon as a diagnosis is made—buying valuable time and potentially stopping the disease before it advances further.

Rethinking How mRNA Vaccines Work Against Cancer

Most people became familiar with mRNA technology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna used messenger RNA to instruct cells to produce a harmless fragment of the coronavirus spike protein. This trained the immune system to recognize and destroy the real virus if it ever appeared.

Sayour’s cancer vaccine relies on the same core technology but applies it in a very different way. Instead of teaching the immune system to recognize a specific target, it essentially sounds a general alarm. The mRNA, delivered through lipid nanoparticles, stimulates the body to produce high levels of type-I interferons—powerful immune signaling molecules that help detect and destroy cancerous cells.

Sayour likens the approach to upgrading a neighborhood’s security system. Rather than handing residents a photo of a single suspect, the vaccine turns on floodlights and motion sensors throughout the entire area. Cancer cells that once hid in the shadows suddenly become visible and vulnerable.

Cancer is notoriously skilled at suppressing immune responses and hijacking normal warning signals. In many patients, immune cells become exhausted or inactive despite the presence of dangerous tumors. By flooding the body with interferons, the vaccine appears to override those suppressed signals and “reset” the immune system, forcing it back into an active, tumor-fighting mode.

Why Personalized Cancer Vaccines Struggle to Scale

For years, cancer vaccine research has followed two main paths. One strategy focuses on finding proteins shared by many patients’ tumors, aiming for a one-size-fits-most solution. The other embraces full personalization, designing vaccines tailored to each patient’s unique cancer profile.

Both approaches have serious drawbacks. Shared tumor proteins are rare, and cancers can quickly evolve to stop producing them. Personalized vaccines, while more precise, are expensive, time-consuming, and difficult to scale.

“It can take months from the time you collect a patient’s tumor sample to the moment they receive their personalized therapy,” Sayour explained. During that period, patients must rely on conventional treatments while their cancer continues to grow and change. When the vaccine finally arrives, it may already be less effective.

Sayour and his colleagues wondered whether they could bypass this entire problem. Instead of teaching the immune system what to look for, what if they simply made it aggressive enough to figure that out on its own?

Mouse Studies Reveal Unexpected Strength

To test this idea, the researchers started with some of the most difficult cancers to treat. They focused on solid tumors, which are typically far more resistant to immunotherapy than blood cancers.

In mice with melanoma, the team combined their mRNA vaccine with a common immunotherapy drug known as a PD-1 inhibitor. PD-1 inhibitors are immune checkpoint drugs that remove the “brakes” cancer places on immune cells. While these drugs can be life-saving for some patients, many tumors remain unresponsive.

When paired with the experimental vaccine, previously resistant tumors began to shrink. Mice that had shown no improvement on checkpoint inhibitors alone suddenly mounted strong anti-cancer responses. The vaccine appeared to make invisible tumors visible again.

Even more striking, the vaccine also showed promise as a standalone treatment. In mouse models of aggressive brain cancer (glioma) and pulmonary osteosarcoma, some tumors shrank dramatically or disappeared entirely without additional therapies.

Researchers observed that dormant T cells—immune cells that had been present but inactive—suddenly began multiplying and attacking cancer once the vaccine was administered. Even immune responses not directly related to cancer seemed capable of triggering these T cells, as long as the vaccine produced a strong enough immune signal.

Turning “Cold” Tumors Hot

Some cancers are especially adept at avoiding immune detection. These so-called “cold” tumors fail to provoke inflammation, making them nearly invisible to the immune system. Pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, and certain breast cancers fall into this category, and patients often see little benefit from current immunotherapies.

Diana Azzam, an associate professor at Florida International University who was not involved in the study, believes this approach could be particularly important for these hard-to-treat cancers.

“By amplifying interferon signaling throughout the body, this vaccine could force cold tumors into the open,” Azzam said. Once exposed, the immune system may finally be able to recognize and attack them.

Cold tumors represent one of oncology’s most stubborn challenges. Patients may initially respond to surgery or chemotherapy, only to experience aggressive recurrences that resist further treatment. A vaccine capable of reversing immune invisibility would mark a major breakthrough.

Human Trials and the Road Ahead

Despite impressive mouse data, many promising cancer treatments fail when tested in humans. Biological systems are far more complex, and results that look dramatic in animals do not always translate to patients.

To address this, UF Health has launched early-stage human trials using a combination strategy. Patients first receive the universal mRNA vaccine to broadly activate their immune systems. Later, they are given a personalized vaccine tailored to their specific tumors.

The trials currently focus on pediatric high-grade glioma and recurrent osteosarcoma—two cancers with limited treatment options and poor prognoses. Sayour believes the dual approach offers the best chance of success, providing immediate immune activation while personalized therapies are prepared.

Before any universal cancer vaccine can reach widespread use, researchers must still answer critical questions about safety, consistency, and long-term effectiveness. Interferons can cause inflammation, and uncontrolled immune activation could lead to serious side effects. Scientists must ensure the response is powerful but temporary and well-regulated.

Dr. Duane Mitchell, co-author of the study and director of the UF Clinical and Translational Science Institute, believes the work represents a potential third path in cancer vaccine development.

“It could be a universal way of waking up a patient’s own immune response to cancer,” Mitchell said. “If this holds true in humans, it could fundamentally change how we approach cancer treatment.”

While years of research still lie ahead, the idea of a universal, off-the-shelf cancer vaccine has moved from theory into real-world testing. For patients with few remaining options, that shift alone offers a new and meaningful source of hope.