Bending Ice Might Be What Sparks Lightning in Storms

Scientists Reveal Ice Can Generate Electricity When Bent — A Breakthrough That Could Explain How Lightning Forms

Scientists have recently uncovered a surprising property of ordinary ice: when it is bent or unevenly deformed, it can actually produce measurable electrical charges. Although ice has long been considered non-piezoelectric — meaning it does not generate an electric charge when simply compressed — new research shows that ice exhibits a phenomenon known as the flexoelectric effect, which causes charges to separate under bending and strain gradients. This discovery has major implications not only for materials science but also for our understanding of how thunderstorms become electrically charged and ultimately produce lightning.

In recent laboratory experiments, researchers from institutions including the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2), Xi’an Jiaotong University, and Stony Brook University created slabs of ultra-pure ice and placed them between metal electrodes. By applying controlled bending forces to the ice, they observed that significant electrical voltages appeared across the samples. The strength and characteristics of these electrical signals were surprisingly similar to those recorded in experiments simulating ice particle collisions in thunderstorms.

Typically, ice is not capable of generating electrical charge through simple compression, because the molecular structure of common ice (called “ice Ih”) aligns in a way that cancels out net piezoelectric effects. However, when the ice is subjected to inhomogeneous deformation — such as bending rather than uniform squeezing — the material responds with a flexoelectric polarization that separates positive and negative charges. This flexoelectric effect exists because mechanical strain gradients can couple with electrical polarization, a physical relationship that is allowed in all insulating materials, including ice.

Beyond flexoelectricity, the researchers also discovered a remarkable secondary property: at extremely low temperatures, specifically below about –113 °C (or ~160 K), the very surface of ice can behave like a ferroelectric material. Ferroelectric materials can develop a spontaneous electric polarization that can be reversed by an external electric field — a bit like flipping the poles of a magnet. This surface layer, only nanometers thick, may further support charge separation under the right atmospheric conditions.

These new findings suggest that ice in thunderstorms is not simply passive; it may actively participate in generating the electrical charges that build up inside clouds. Lightning — one of nature’s most dramatic electrical discharges — originates when strong electric fields develop within storm systems. These fields form as positive and negative charges in the cloud become separated over time. Until now, scientists have understood that collisions between small ice crystals and larger graupel (soft hail) particles help create this charge imbalance, but the precise mechanism for how these collisions generate charge has remained elusive. Traditional explanations could not fully account for the observed electricity because classic piezoelectricity does not occur in ice.

The newly observed flexoelectric behavior offers a compelling answer. In a thunderstorm’s highly turbulent environment, ice particles are constantly twisting, bending, and colliding with each other and with other hydrometeors. These irregular deformations, according to the researchers’ models, can produce sufficient electrical charge via flexoelectric effects to match the amounts measured in laboratory simulations of cloud electrification. Over many such interactions, these small charges can build up into the large electrical potentials that eventually trigger lightning strikes.

While the study does not claim to fully solve the complex mystery of lightning formation — a process influenced by many atmospheric variables — it provides a significant piece of the puzzle. The combined effects of flexoelectric charge generation and surface ferroelectricity in ice help explain how particles deep within clouds can become charged without conventional piezoelectric mechanisms.

Beyond weather science, this discovery may also inspire new applications in cold-climate electronics and energy harvesting technologies. Because ice exhibits flexoelectric properties similar in magnitude to well-known ceramic materials like titanium dioxide, researchers speculate that ice could someday be used in specialized mechanical-to-electrical transducers or sensors designed to operate in frigid environments.

In summary, this breakthrough demonstrates that ice can generate electrical charge through bending and deformation, a property rooted in flexoelectricity and supported by ferroelectric surface behavior at ultracold temperatures. These mechanisms may play important roles in the charge separation that precedes lightning in thunderstorms, giving scientists new insight into one of nature’s most electrifying phenomena.

In addition to these laboratory findings, the new understanding of ice’s electromechanical behavior aligns with well-established theories of thunderstorm electrification that involve interactions between different types of hydrometeors (ice and liquid water particles) within the mixed-phase region of a cloud. According to classical meteorological models, charge separation in clouds arises when larger, heavier particles such as graupel (soft hail) fall through a cloud while smaller ice crystals are carried upward by updrafts; the collisions and subsequent rebounds between these particles cause one group to become more negatively charged and the other more positive, leading to a charge separation that allows an electric field to grow between cloud regions.

However, while this general mechanism of collision-induced charging has long been accepted, the specific physical process by which ice particles acquire their charge has remained unclear because ice itself is not piezoelectric — it does not generate charge simply from being uniformly compressed. What the recent research contributes is a plausible microscopic explanation: the flexoelectric effect in ice may be the underlying cause of the charge generation during the irregular, turbulent deformations that occur in cloud collisions. In other words, each contact event between ice crystals and other ice particles may incur tiny bends or strain gradients that induce an electric potential through flexoelectric polarization, gradually building up the large charge separations necessary to produce lightning.

Meteorological studies further show that factors such as aerosol concentrations and secondary ice production processes influence cloud microphysics and the intensity of lightning activity. For instance, research using cloud-resolving models indicates that when more ice crystals are generated in a storm, the frequency and strength of cloud electrification — and thus lightning — tend to increase because more opportunities exist for collisions between charged particles. This suggests that ice particle behavior is a key control on how rapidly and how strongly a storm electrifies, making the new flexoelectric insights even more relevant to understanding real atmospheric conditions.

It is also important to consider that lightning initiation itself — the moment a leader channel forms and a discharge occurs — may involve additional physical processes. Some theoretical work indicates that free electrons within a cloud can be accelerated by the strong electric fields created by charge separation, producing avalanches of ionization that help start the discharge. While this photoelectric feedback process pertains specifically to how lightning is triggered once a large field exists, the build-up of that field still depends on the collective effects of charging mechanisms including ice particle interactions.

Taken together, these lines of evidence help paint a more complete picture of atmospheric electricity: ice is not simply a passive component of clouds but may play an active role in generating and enhancing the charge separations that lead to thunderstorms and lightning strikes. The discovery of flexoelectricity in ice now connects detailed solid-state physics with large-scale atmospheric phenomena, advancing both fields simultaneously.

Beyond improving our fundamental understanding of weather, this knowledge may have practical implications for weather prediction and lightning risk assessment. Better physical models of cloud electrification can help meteorologists predict where and when strong electric fields — and thus lightning hazards — are more likely to develop, potentially improving early warning systems. In addition, engineers and materials scientists are now exploring how ice’s electromechanical properties could inspire new devices and sensors designed to operate in cold environments or even to harness mechanical deformation directly as a source of electricity.

In conclusion, the realization that bending ice can generate electric charge through flexoelectric and ferroelectric effects represents a significant advance in both physics and atmospheric science. This breakthrough helps bridge gaps in our understanding of how thunderclouds become highly charged and ultimately produce lightning, revealing that the behavior of ice — once considered electrically inert — has a dynamic and crucial role in nature’s most spectacular electrical displays.

News in the same category

Woman Donates Entire $1B Fortune to Eliminate Tuition in NYC’s Poorest Area

Psychologists Reveal 9 Activities Associated with High Cognitive Ability

Japan’s 2025 Space Solar Power Test Brings Wireless Energy From Orbit Closer to Reality

Metabolic Interventions in Oncology: The Impact of a Ketogenic Diet on Colorectal Tumor Progression

The Anti-Aging Potential of Theobromine: Slowing the Biological Clock

The Role of the Ketogenic Diet in Suppressing Colorectal Tumor Growth through Microbiome Modulation

Reversing Liver Fibrosis: The Therapeutic Potential of Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid in NAFLD

Metabolic Reprogramming: The Role of the Ketogenic Diet in Suppressing Colorectal Tumor Growth

The Impact of Ketogenic Diet on Colorectal Cancer: Microbiome Reshaping and Long-term Suppression

Fish oil supplement reduces serious cardiovascular events by 43% in patients on dialysis, clinical trial finds.

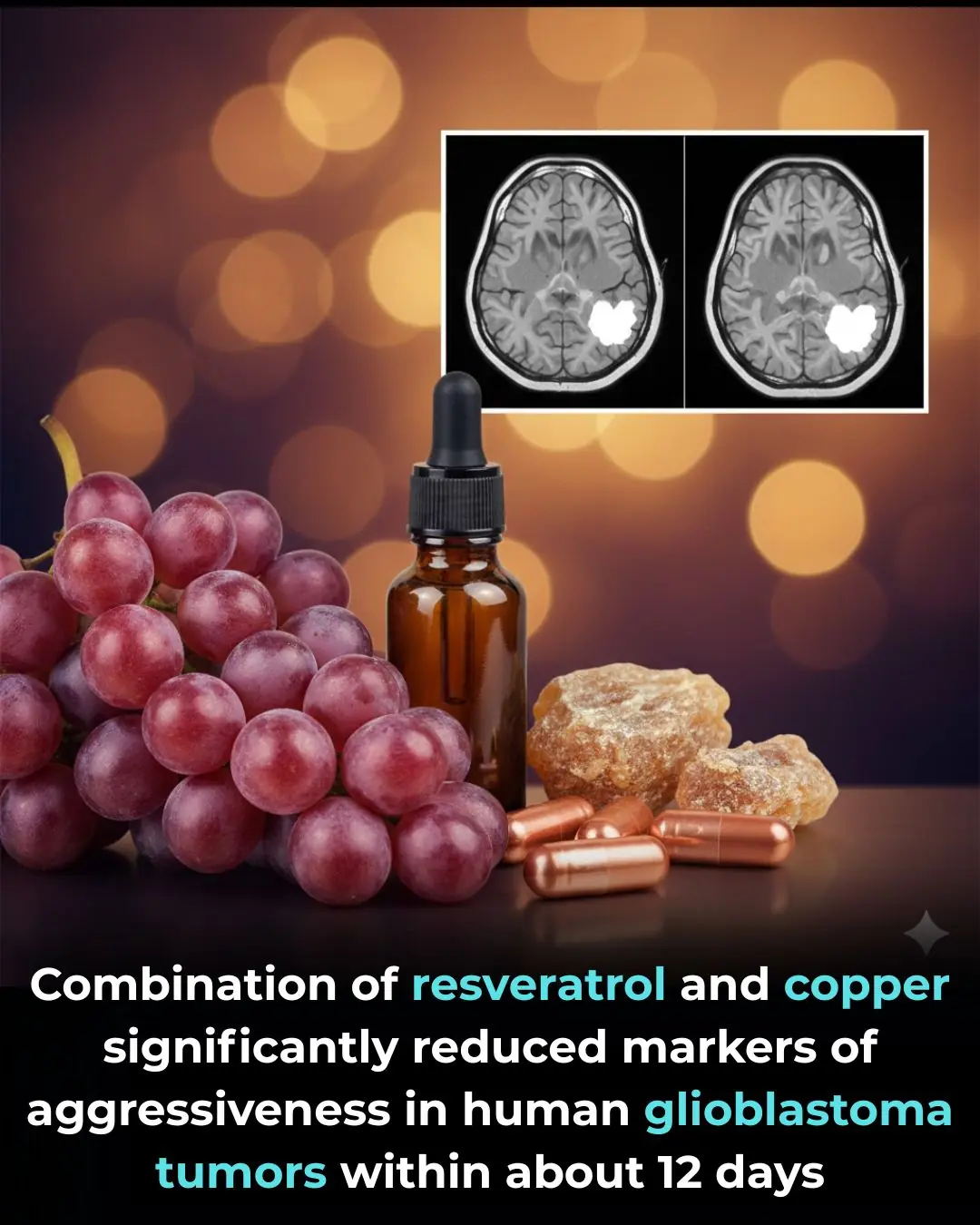

Combination of resveratrol and copper significantly reduced markers of aggressiveness in human glioblastoma tumors within about 12 days.

Astronomers Discover Earth-Sized Planet in the Habitable Zone Just 40 Light-Years Away

A Single Photon Powers the World’s Smallest Quantum Computer

The Most Dangerous Insect In The World Has Appeared

13 Clear Signs Your Man Might Be Cheating on You

11 Quiet Habits of Adults Who Didn’t Feel Loved as Kids

Scientists Finally Explain Why Certain Songs Always Get Stuck in Your Head

Purdue University’s Ultra-White Paint: A Breakthrough in Passive Radiative Cooling Technology

News Post

Voyager 1 Is About to Be One Full Light-Day Away from Earth

Doctor, 30, died seven months after cancer diagnosis following unusual symptom

After the age of 70, never let anyone do this to you

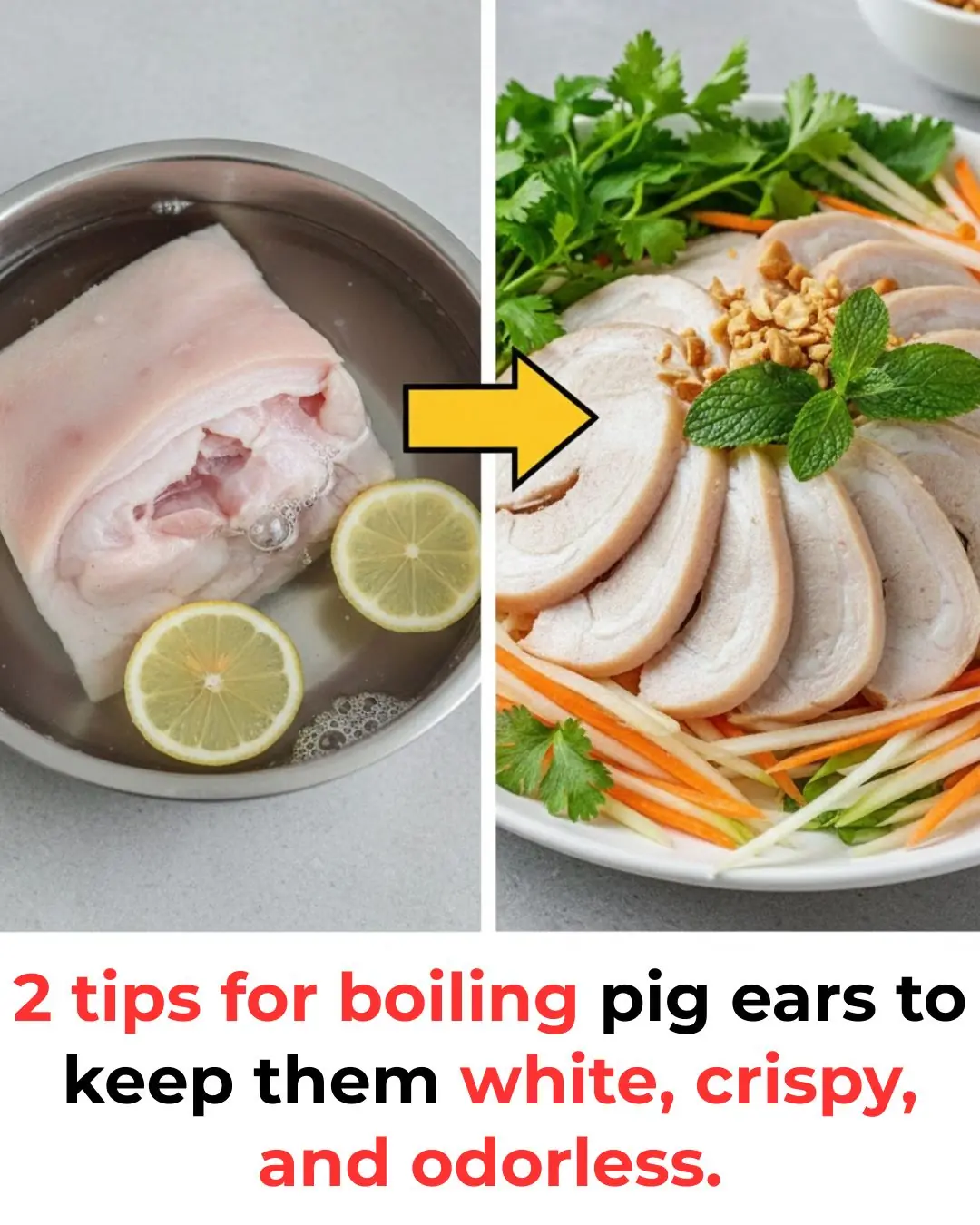

2 tips for boiling pig ears to keep them white, crispy, and odorless.

Tips for cleaning greasy plastic and glass containers without scrubbing.

Is your pan losing its non-stick coating? Add a few drops of this, and your old pan will be like new again.

Support Joint Health Naturally

The Most Dangerous Time to Sleep

Doctor Shares Three Warning Signs That May Appear Days Before a Stroke

A Couple Diagnosed with Liver Cancer at the Same Time: When Doctors Opened the Refrigerator, They Were Alarmed and Said, “Throw It Away Immediately!”

Expanded Summary of the PISCES Trial

Resveratrol–Copper Combination Shows Promise in Altering Glioblastoma Biology

Your hair is aging you. 10 winter styling tweaks that instantly lift your look

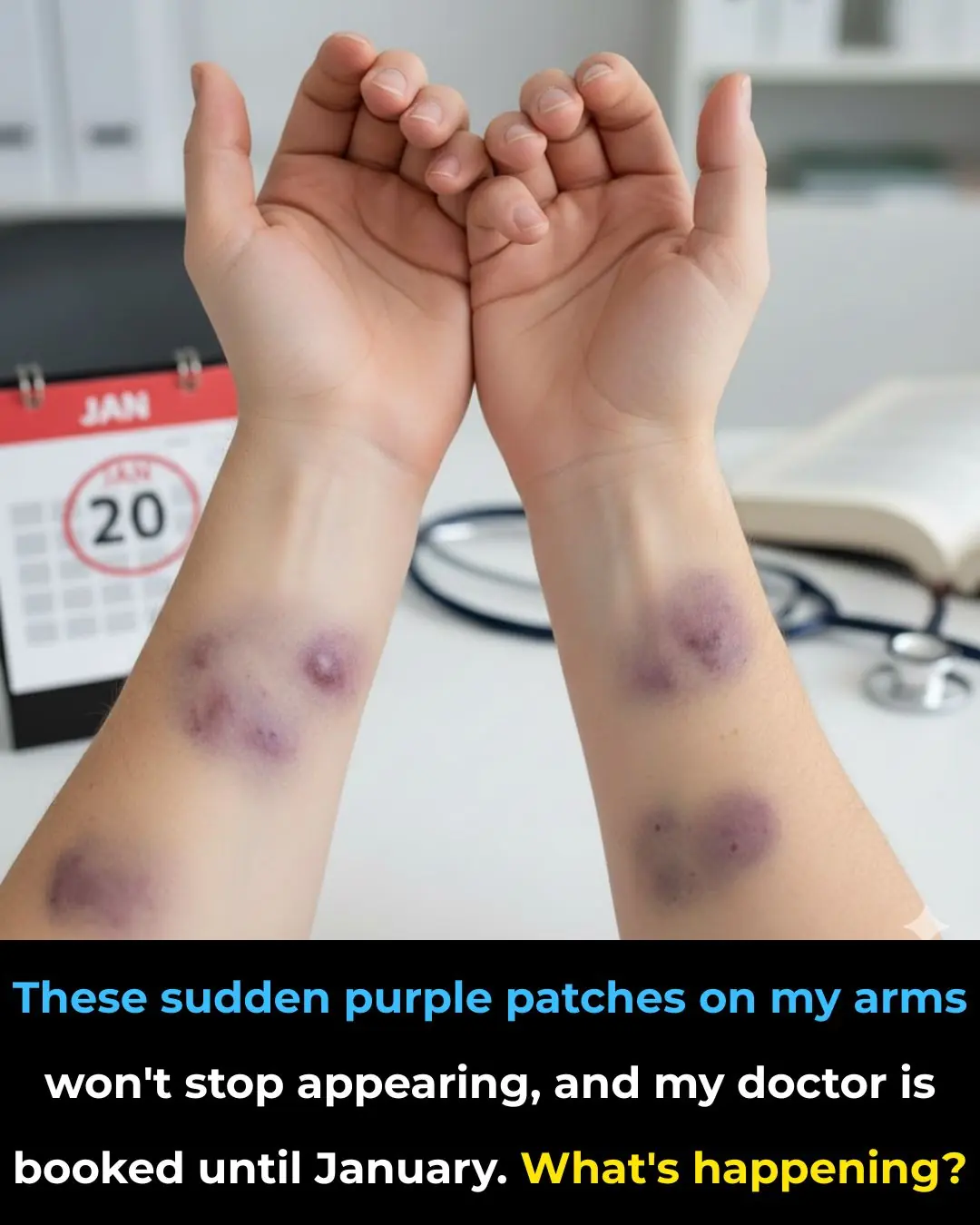

These sudden purple patches on my arms won’t stop appearing, and my doctor is booked until January. What’s happening?

My ankles puff up every evening, and I can’t get in to see anyone until after the holidays. Should I worry?

I had no idea about this

Early Signs of Kidney Disease & How to Protect Your Kidneys (Evidence Based)

Sore Legs for No Reason: What It Means According to Science