Scientists Crack an “Impossible” Cancer Target With a Promising New Drug

For many decades, scientists have viewed a protein known as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) as one of the most elusive targets in cancer research. PCNA plays a central role in DNA replication and repair, acting as a molecular “hub” that allows cells to divide and survive genetic damage. Because this protein is also essential for normal cell function, it was long believed to be impossible to block PCNA without causing severe harm to healthy tissue. However, recent research has challenged this assumption with the development of a novel experimental drug called AOH1996.

AOH1996 has demonstrated striking potential by selectively attacking cancer cells while sparing healthy ones. According to researchers at City of Hope National Medical Center, the drug targets a cancer-specific form of PCNA that is structurally different from the version found in normal cells. This subtle but critical difference allows AOH1996 to disrupt the processes cancer cells depend on, without interfering with normal cellular activity. As a result, the drug represents a new strategy for targeting one of cancer’s most fundamental survival mechanisms.

In laboratory and animal studies, AOH1996 was tested against more than seventy types of cancer, including breast, lung, ovarian, prostate, brain, and skin cancers. The results were highly encouraging. The drug interfered with the ability of tumor cells to copy and repair damaged DNA, a process that cancer cells rely on heavily due to their rapid and unstable growth. When this repair system was shut down, cancer cells became trapped in a destructive cycle of DNA damage, ultimately leading to cell death. Importantly, healthy cells were largely unaffected, as they do not depend on the altered PCNA form targeted by the drug.

Researchers have described the effect of AOH1996 as disabling a critical control center within cancer cells. Without access to this central hub, tumor cells lose their ability to proliferate and survive. This discovery is particularly significant because PCNA is involved in multiple pathways essential to cancer progression, meaning that blocking it could have broad and lasting effects across many tumor types. Similar findings have been highlighted in peer-reviewed journals such as Nature Cancer and Cancer Research, which emphasize the importance of targeting DNA repair mechanisms in modern oncology.

Another promising aspect of AOH1996 is its potential to enhance the effectiveness of existing cancer treatments. Early studies suggest that tumors treated with AOH1996 become more sensitive to chemotherapy and radiation therapy, both of which rely on overwhelming cancer cells with DNA damage. By weakening the tumor’s repair defenses, AOH1996 may allow lower doses of conventional treatments to be used, potentially reducing side effects for patients. This combination approach aligns with current trends in cancer research, as noted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR).

Although the findings so far are based on laboratory and animal experiments, the research has advanced to an important new stage. The first Phase 1 clinical trial in humans is currently underway at City of Hope Medical Center to evaluate the drug’s safety and optimal dosage. While it will take time to determine its full effectiveness in patients, experts are cautiously optimistic. If successful, AOH1996 could represent a major breakthrough in the treatment of solid tumors, offering a more precise and less toxic alternative to many existing therapies.

In the broader context of cancer research, this development underscores the growing shift toward targeted treatments that exploit unique vulnerabilities in cancer cells. As organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) continue to emphasize personalized and precision medicine, AOH1996 may become an important example of how once “undruggable” targets can finally be overcome through innovative science.

Building on these early successes, scientists emphasize that the development of AOH1996 reflects years of accumulated progress in understanding how cancer cells differ from normal cells at the molecular level. For a long time, cancer therapy focused primarily on killing rapidly dividing cells, a strategy that often harmed healthy tissues such as hair follicles, bone marrow, and the digestive tract. In contrast, AOH1996 represents a more refined approach—one that exploits a molecular weakness unique to cancer cells rather than relying on indiscriminate destruction. This shift mirrors a broader transformation in oncology, where precision and selectivity are increasingly seen as the keys to long-term treatment success.

Researchers involved in the project note that the discovery of a cancer-specific form of PCNA was a turning point. Advanced imaging techniques and molecular analysis revealed that PCNA in tumor cells adopts a distinct configuration, enabling it to interact differently with DNA repair enzymes. This altered structure appears to support the uncontrolled growth and resilience of cancer cells under constant genetic stress. By binding specifically to this variant, AOH1996 effectively “locks” PCNA into an inactive state, preventing it from coordinating DNA replication and repair. Studies published in journals such as Science Translational Medicine suggest that this targeted interference could reduce the likelihood of drug resistance, a major challenge faced by many current cancer therapies.

Another important implication of this research lies in its potential impact on patient quality of life. Because AOH1996 does not significantly affect normal cells, it may lead to fewer and less severe side effects compared to traditional chemotherapy. Oncologists have long sought treatments that can be administered over longer periods without debilitating toxicity, particularly for patients with chronic or advanced cancers. If ongoing clinical trials confirm the drug’s safety profile, AOH1996 could offer a more sustainable treatment option, allowing patients to maintain a better quality of life while controlling disease progression.

Experts also highlight the broader significance of targeting DNA repair pathways in cancer. Cancer cells are notoriously dependent on these pathways to survive the constant accumulation of mutations caused by rapid division and environmental stress. By disrupting this dependence, therapies like AOH1996 may push cancer cells beyond their ability to adapt. According to analyses from the National Institutes of Health and reviews in The Lancet Oncology, combining DNA repair inhibitors with immunotherapy or targeted drugs could further amplify anti-tumor responses, opening the door to more effective combination regimens.

As the Phase 1 clinical trial progresses, researchers will closely monitor not only safety and dosage, but also early signals of effectiveness across different tumor types. While it remains too early to predict clinical outcomes, the enthusiasm surrounding AOH1996 reflects a growing belief that even long-standing “undruggable” targets can be conquered with innovative design and deeper biological insight. Should these trials prove successful, AOH1996 may mark the beginning of a new class of cancer treatments—ones that strike at the very core of cancer cell survival while leaving healthy tissue largely intact, reshaping the future of solid tumor therapy.

News in the same category

People Who Were Raised By Strict Parents Often Develop These 10 Quiet Habits

Six Money-Saving Habits That Can Quietly Increase Cancer Risk

Pouring Hot Water on Apples: A Simple Way to Detect Preservatives

9 Strange Feelings You’ll Experience Around People Who Aren’t Good for You

Scientists Discover Bats in the US Can Glow A Ghostly Green — and No One Knows Why

Voyager 1 Is About to Be One Full Light-Day Away from Earth

Bending Ice Might Be What Sparks Lightning in Storms

Woman Donates Entire $1B Fortune to Eliminate Tuition in NYC’s Poorest Area

Psychologists Reveal 9 Activities Associated with High Cognitive Ability

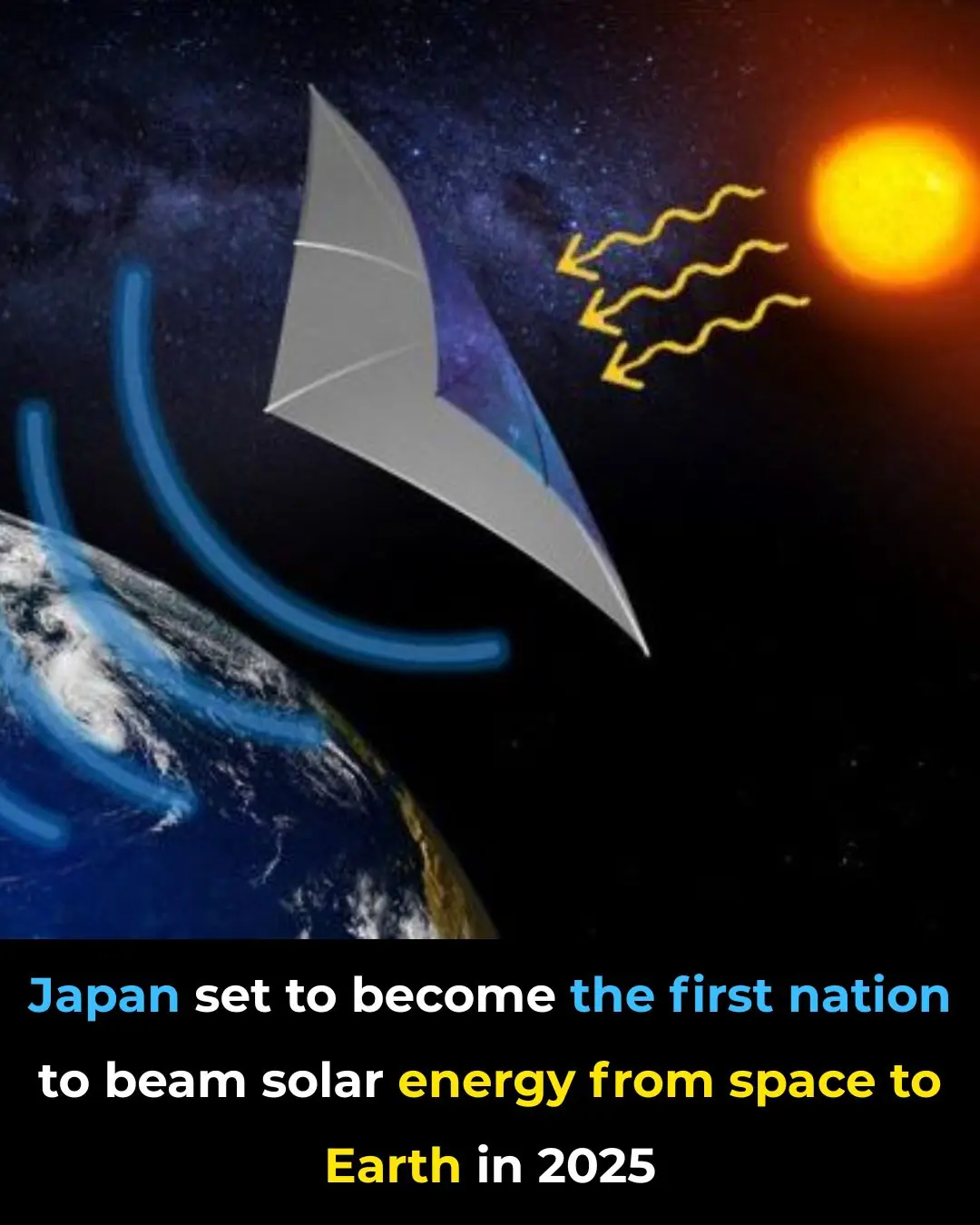

Japan’s 2025 Space Solar Power Test Brings Wireless Energy From Orbit Closer to Reality

Metabolic Interventions in Oncology: The Impact of a Ketogenic Diet on Colorectal Tumor Progression

The Anti-Aging Potential of Theobromine: Slowing the Biological Clock

The Role of the Ketogenic Diet in Suppressing Colorectal Tumor Growth through Microbiome Modulation

Reversing Liver Fibrosis: The Therapeutic Potential of Vitamin B12 and Folic Acid in NAFLD

Metabolic Reprogramming: The Role of the Ketogenic Diet in Suppressing Colorectal Tumor Growth

The Impact of Ketogenic Diet on Colorectal Cancer: Microbiome Reshaping and Long-term Suppression

Fish oil supplement reduces serious cardiovascular events by 43% in patients on dialysis, clinical trial finds.

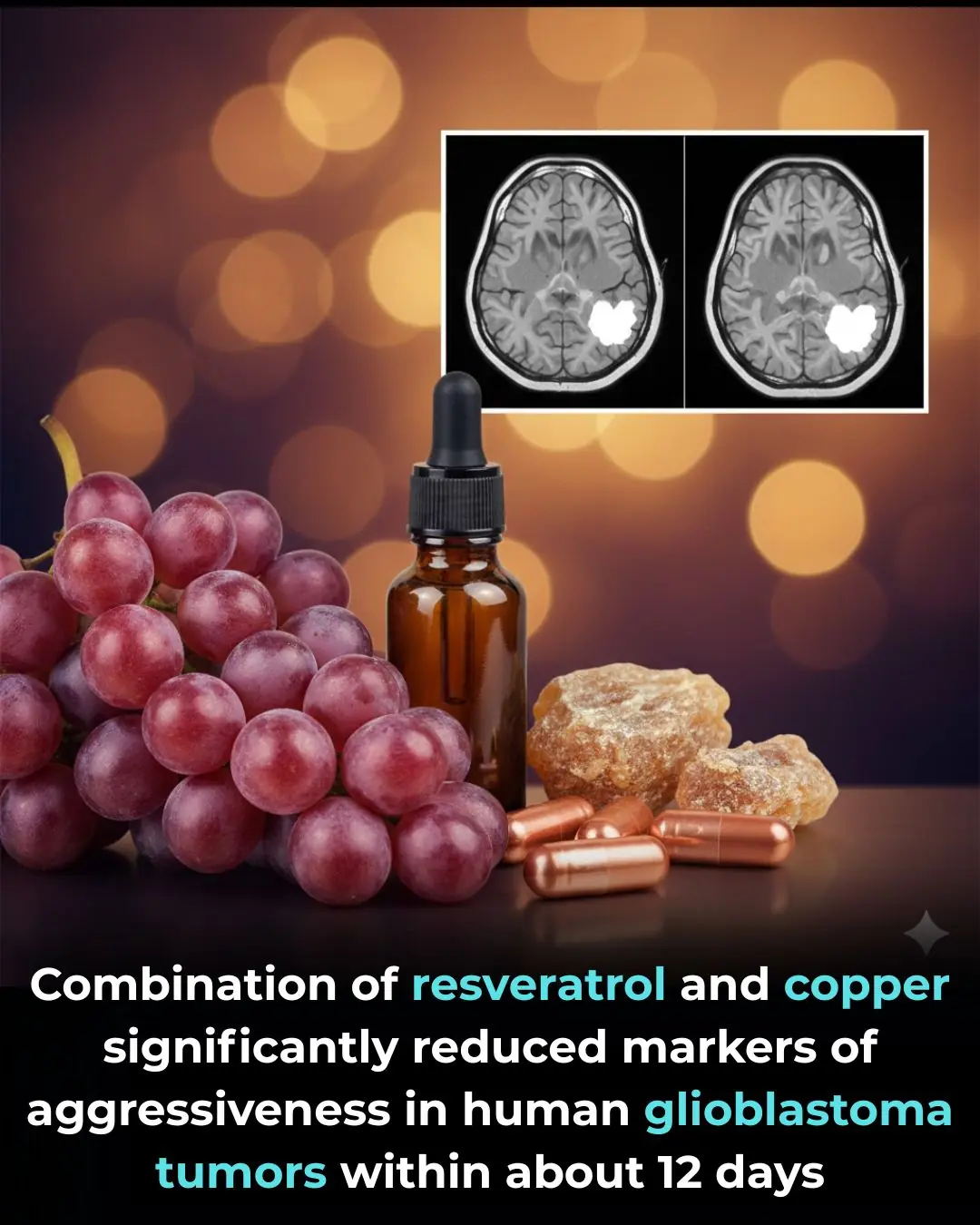

Combination of resveratrol and copper significantly reduced markers of aggressiveness in human glioblastoma tumors within about 12 days.

News Post

How to grow lemons in pots for abundant fruit all year round, more than enough for the whole family to eat

Regularly using these three types of cooking oil can lead to liver cancer without you even realizing it.

6 tips for using beer as a hair mask or shampoo to make hair shiny, dark, and reduce hair loss

When rendering pork fat, don't just put it directly into the pan. Adding this extra step ensures that every batch of pork fat is perfectly white and won't mold even after a long time.

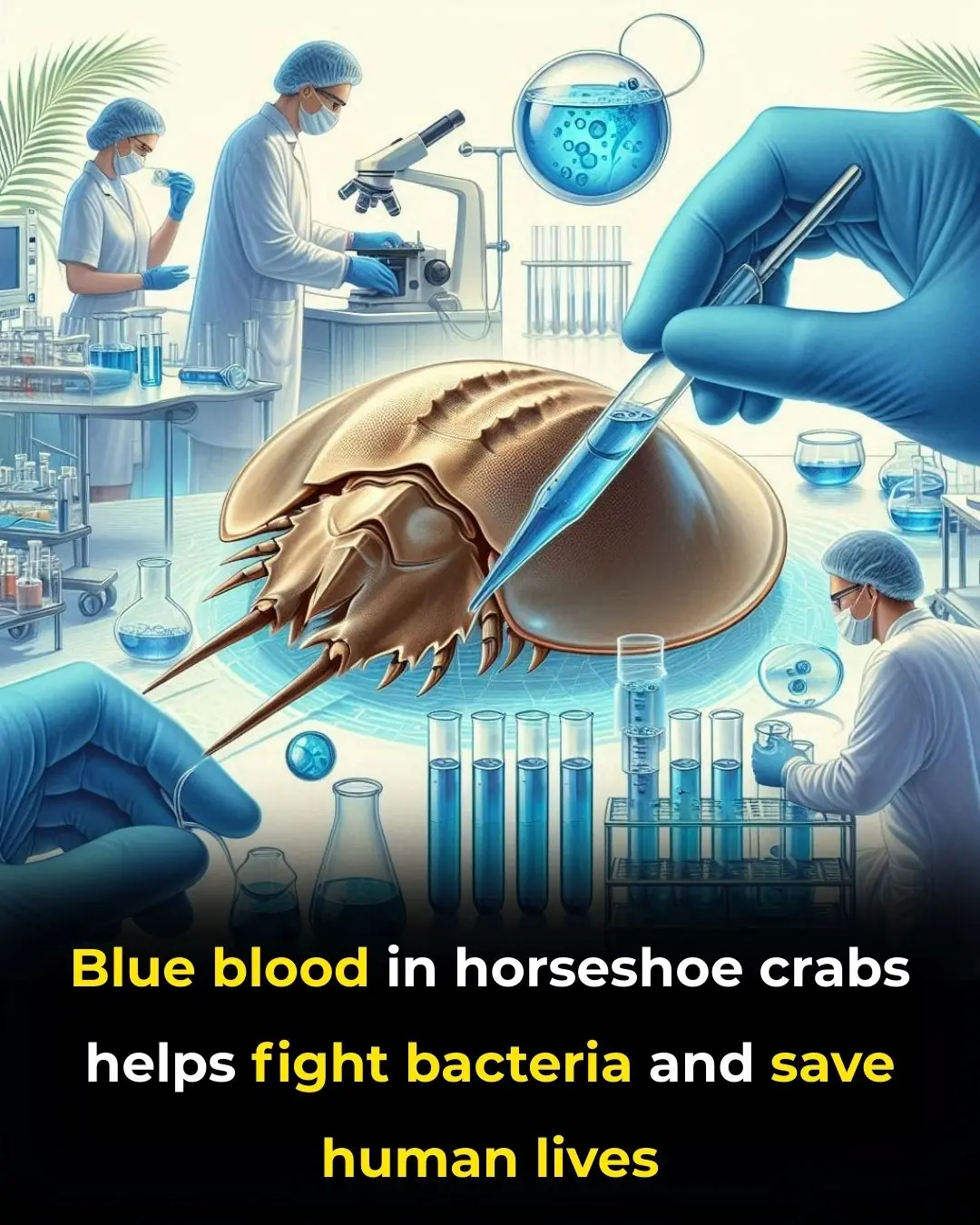

Blue Blood in the Ocean: How Horseshoe Crabs Help Protect Human Health

Using an electric kettle to boil water: 9 out of 10 households make this mistake, so remind your family members to correct it soon

4 "cancer culprits" lurking in your home, many people are exposed to daily without knowing it

Three "strange" red spots on the body are actually signs of cancer that very few people notice

5 foot changes that signal liver "exhaustion," a sign that you may have had liver cancer for a long time.

10 types of fruits and vegetables you should never put in the refrigerator; many people don't know this and end up doing it wrong, ruining the taste and causing them to spoil quickly.

You were raised by emotionally manipulative parents if you heard these 8 phrases as a child

The reason some seniors decline after moving to nursing homes

If You Love Being Alone, You Probably Have These 10 Qualities Others Envy

People Who Were Raised By Strict Parents Often Develop These 10 Quiet Habits

Sauna Bathing and Long-Term Cardiovascular Health: Evidence from a Finnish Cohort Study

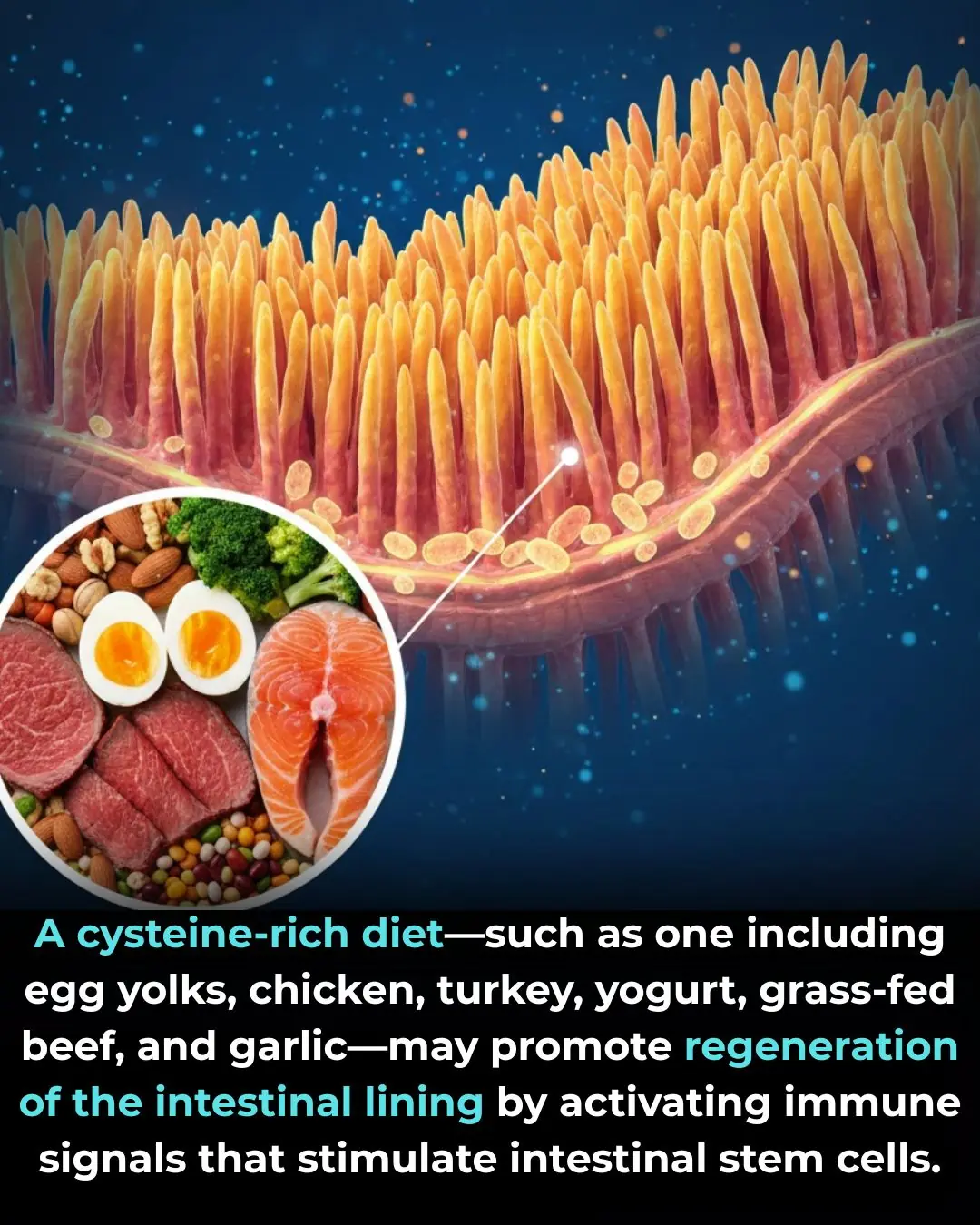

The Role of Dietary Cysteine in Intestinal Repair and Regeneration

Researchers found that 6-gingerol, the main bioactive compound in ginger root, can specifically stop the growth of colon cancer cells while leaving normal colon cells unharmed in lab tests

Powerful Piriformis Stretch to Soothe Sciatic, Hip, and Lower Back Pain